The trajectory of the Godzilla filmography is ongoing, shifting between nuclear metaphor and more standard daikaiju material–once defiled by an American studio and currently in the process of being rebooted with next year’s film from Legendary.

The trajectory of the Godzilla filmography is ongoing, shifting between nuclear metaphor and more standard daikaiju material–once defiled by an American studio and currently in the process of being rebooted with next year’s film from Legendary.

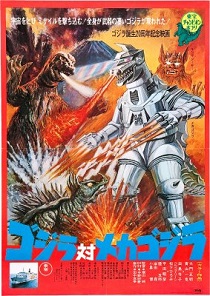

But 20 years after the release of the original version–a bleak and serious horror incarnation, ironically the progenitor of a genre that mostly skirted its roots in years to come (not unlike the Godzilla series itself)–Toho released Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla, perhaps the ultimate iteration (and logical culmination) of the character after two decades of material.

As beloved as the American side of the monster movie genre had been, with Ray Harryhausen following in the footsteps of Willis O’Brien, crafting decades of iconic stop-motion creatures (beginning in 1925 with The Lost World and by extension King Kong in 1933, and ending roughly 50 years later with Clash of the Titans in 1981), the sheer scale and scope of the Japanese movement from Gojira (1954) on set it apart in a number of ways.

Where stop-motion animation approximated movement more fluidly and with a broader range of detail, speed and weight were always more convincing with the suit-mation employed in the kaiju era. The restrictiveness of the costumes, particularly in the case of Godzilla, enhanced the plodding, methodical posture and movements of the creatures that were actually more in line with the reality of the physics of something that size.

In the case of Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla, it afforded Toho an opportunity for some of the best costume work of the entire series. Godzilla appears better than ever, with two separate costumes used in the film, and endures an astronomical amount of blood loss in both encounters with the title villain. The mammalian daikaiju King Caesar (see-saw) is another sound creation, a kind of demonic Sphinx with an unmistakable Cowardly Lion-vibe hatched from a mountain by a protracted musical number. Nothing’s perfect.

But Mechagodzilla is of course the central creation–my vote for the best of the first run, and a candidate for best of the entire series. A massive robot built to mirror Godzilla’s appearance, set loose by alien invaders hellbent on colonizing the planet, its metal plating and ubiquitous gadgetry are incredibly well realized, and the FX for lasers and force fields on display are some of the best of all tokusatsu of that period.

The followup in 1975 pitted an additional enemy against Godzilla, lost King Caesar as an ally, and toned down some of the more outlandish elements of the Space Ape alien invaders–still sheathed in chrome jumpsuits though no longer reverting to gorilla form when injured or killed, for example. After that film, Godzilla would go on hiatus until the mid-80s, spawning an additional set of separate series, punctuated by an American abortion in 1998.

At the end of the day, the evolution from Hiroshima parable to science fiction anti-hero was mostly successful, and struck a kind of sublime balance with Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla. The B-movie sci-fi angle of the back story integrated into the basic dynamic of Godzilla fighting other monsters (itself a B-movie sci-fi angle) pays off in a way almost no other entry does on either side. Ironically, the ultimate example of that cartoon flexibility being Mechagodzilla itself.

A reasonable person can make a case for humanoid mechas presented in the likes of Pacific Rim or its predecessors, but the fact of the matter is the construction of a robot made to look like Godzilla is insane. I understand they wanted to frame him for property damage, and I appreciate the Terminator-style reveal with the iconic score more than most, but let’s be serious: The later appearances still work because of built-in, genre-specific reasons, and because the technology had stagnated in many ways. This is a creation preserved for its era, and that’s not a bad thing.

Anniversaries are hit and miss in the Godzilla universe, but this overlooked entry (obscured by remakes and awkward chronological positioning) is one of the best. It crystallizes an era and bygone approach to film making, with a technical sophistication and entertainment value outclassed by few of its contemporaries.

Comments on this entry are closed.