Something very strange is happening this Friday – a Hollywood studio is releasing a mid-budget character-based thriller not aimed squarely at the teenage market. That movie is Arbitrage, and despite its low marketing profile, it’s not a movie worth missing. Built around a performance from Richard Gere that will surely build award season buzz, Arbitrage sets up a story of big money and what happens to the power players who try to keep it all from toppling down.

Something very strange is happening this Friday – a Hollywood studio is releasing a mid-budget character-based thriller not aimed squarely at the teenage market. That movie is Arbitrage, and despite its low marketing profile, it’s not a movie worth missing. Built around a performance from Richard Gere that will surely build award season buzz, Arbitrage sets up a story of big money and what happens to the power players who try to keep it all from toppling down.

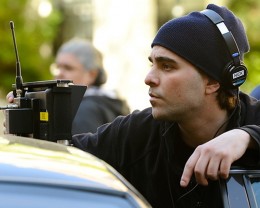

Arbitrage is the first fictional feature film from writer-director Nicholas Jarecki. Despite his rookie status, the 33-year-old has pulled off a complex story with a clean classiness we don’t see enough in the movies. I recently spoke with Jarecki about Gere’s work on the film, how the actor and director both had different ideas about the character, and how his Wall Street story will play in an election year. Vague discussions of the film’s end ensue, so those super-averse to spoilers, be warned!

Ian McFarland: So my main question I had coming out of the movie was if we’re supposed to cheer on Robert Miller, played by Richard Gere.

Nicholas Jarecki: Well, I think that you hopefully understand Robert Miller. I don’t know that really anyone could be cheering or looking up to murder and mayhem. But as with the best gangster tales, I think you hopefully empathize with him as to why he makes the choices that he does, even if you understand as a citizen that they’re really pretty questionable. He’s an extreme character, and I’m fascinated by Michael Corleone and Rick from Casablanca, those kind of guys.

IM: It’s interesting that you mention he’s an extreme character because Richard Gere gives, what seems to me at least, a pretty relatively calm performance. You usually see powerful characters like that as being huge and bloated. How do you get an actor to carry a story so effectively when he’s not going big like that?

NJ: Well I think you pick up on something that’s really nice about Richard’s performance – the restraint he shows in it, and the fact that he plays the conflict more internally as opposed to like a big scenery-chewing scene.

NJ: Well I think you pick up on something that’s really nice about Richard’s performance – the restraint he shows in it, and the fact that he plays the conflict more internally as opposed to like a big scenery-chewing scene.

I love scenery chewing, I love it when they’re like “YOU THINK IT’S SO EASY!?” [Richard] didn’t do that, he really played it much more closely to the vest – but you know, then there are those colons punctuated throughout the film where he’s in his limo screaming at his associate, orwhen he’s yelling at his daughter just in that brief second.

He knows how to effectively manipulate those people that love him or that want something from him or want to be around him, but he’s gotta exude that charm as confidence. I think that Richard maybe was inspired by different people – maybe Clinton – just somebody that you can’t help but love love, even if he’s kind of telling you some real bullshit.

IM: You say he manipulates his family but, the way that he talks to them, you can’t tell if he’s convinced himself that he does everything for them, or if he understands that he’s acting selfishly some of the time. Do you think that character understands, or is he putting on a ruse so big that he’s fallen for it?

NJ: I think that he’s a compartmentalizer. So when he says he loves his family, I think he means it and he loves being around them. [But] when he says he loves his mistress, I think he means that too. He would like to have them all, and he’s money to make it nearly possible.

I think that he feels all of these things, but reconciling them is a little more different. Clearly he says throughout the whole film that he’s doing various things for the greater good, he’s trying to protect these people and [his] employees. All of those things are true- probably many people in this story are better off for having known Robert. But does he use this for justification for doing whatever the fuck he wants?

IM: Arbitrage has a large supporting cast with a lot of character arcs that come out of Robert’s story. When you wrote the script, how did you go about balancing each characters’ story to do them all justice, and feed them all into the larger story?

NJ: It was tricky to balance. There were six characters, with him at the center, and it was almost like a bicycle spoke. There he was, we could shoot it out to somebody else for a minute, but whatever we were seeing in their story had to relate back to Robert and back to the scene. So we could make short trips, but we couldn’t leave for too long or we’d miss him. In the editing room actually, we dealt with some of that where we’d go, “Oh man, now we’re too far away, let’s take him back in. But how do we get out of this scene?” I think it was a lot of tinkering with the script, and then once we were in the editing room it was a lot of trial-and-error just to find the right balance and the right feel until everything was on the theme.

NJ: It was tricky to balance. There were six characters, with him at the center, and it was almost like a bicycle spoke. There he was, we could shoot it out to somebody else for a minute, but whatever we were seeing in their story had to relate back to Robert and back to the scene. So we could make short trips, but we couldn’t leave for too long or we’d miss him. In the editing room actually, we dealt with some of that where we’d go, “Oh man, now we’re too far away, let’s take him back in. But how do we get out of this scene?” I think it was a lot of tinkering with the script, and then once we were in the editing room it was a lot of trial-and-error just to find the right balance and the right feel until everything was on the theme.

This film runs a nice 100 minutes now, (but) the first cut was two-and-a-half hours – there were things that had to go, that we didn’t have time for because we had to stay on the theme

IM: So the movie doesn’t have a happy ending for everyone, but all things considered, it ends pretty well for most of the characters. But it still has kind of an unsatisfying feel – why do you think that is?

NJ: I tried to end this film as I felt it would happen. What would everybody do? Would his daughter compromise himself for him or not? Would he get his friend in trouble or not? What for him was lost? Would they beat him and catch him, or would he get away? I think that he – I don’t want to say he walks away without consequence, but he’s a very inventive chess player, so with regards to traditional punishment, he’s pretty inventive.

As far as his emotional relationships, I think that they’re a little more compromised by the end of the film. And whether or not he’ll be able to restore them, that was the debate that Richard and I had. Could a person like this ever get back in? Richard thought that he could and that his wife (and daughter would be right back. I was a little more left wondering whether or not it would be possible to save his relationships

IM: So did you ever write another scene after the one we see on screen, or was that the intended ending?

NJ: No, I never wrote anything else, that was always it.

NJ: No, I never wrote anything else, that was always it.

IM: Arbitrage treads on very hot political territory right now, but there’s no real political motive in the film that I can discern – it’s not a message movie. Were you considering any political implications while writing it, and what the reaction would be to them?

NJ: No. Harry Kohn says if you want to send a message, use Western Union. This film is entertainment, it’s for you a have a good time and maybe provoke some larger topics. But it’s there to satisfy you as any film does. I don’t know anybody that’s changed their whole life because of a movie. David Mamet says the greatest tool to create social change is called a gun.

But, I think if there’s anything to take from this movie as far as understanding where this guy comes from, and having the satisfaction that we don’t have to label everybody a villain, is that there might be forces moving them [that we should] observe. If anybody was to do anything, [they might] become more educated about the system. If we’re going to change anything in the system, people have to know it. I think most people don’t know where their money goes – find out what the fine print in your retirement plan is. Are they ripping you off with fees? Are they taking risks? Hold them accountable, it’s your money.

IM: Do you worry that people could read the synopsis of Arbitrage and dismiss it as a message film in an election year?

IM: Do you worry that people could read the synopsis of Arbitrage and dismiss it as a message film in an election year?

NJ: No, I don’t think so. I think that the word is out a little bit on the fine performances of this cast, especially Richard doing something that I really haven’t seen him do before. The craft and the dedication of everybody involved . . . I think there’s something on display here that hopefully will satisfy and entertain people. As for its connection to the election, that’s purely coincidental – maybe (laughs).

Comments on this entry are closed.