Wes Anderson appears to truly revel in being Wes Anderson, and why shouldn’t he? He’s got a devoted throng of seething admirers that want him to do nothing, but what he’s become known for – quirky memorable characters, and oddly synthetic moments.

Wes Anderson appears to truly revel in being Wes Anderson, and why shouldn’t he? He’s got a devoted throng of seething admirers that want him to do nothing, but what he’s become known for – quirky memorable characters, and oddly synthetic moments.

When Anderson’s on these idiosyncratic characters and their apparently fictional worlds add poignancy to truths buried within his stories.

Max Fischer’s delusional brilliance in Rushmore hits home when juxtaposing his staged version of Serpico with his outlandish behavior towards Herman Blume and his job as a barber working with his father. We see more clearly the desperation in Dignan as his quiet digressions in regards to his mother and poverty continue throughout Bottle Rocket and are paired with his wide-eyed nature and total lack of cynicism.

Somewhere around The Royal Tenebaums or perhaps as late as The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, Anderson’s love of his own Wes Anderson-isms, overt and showy camera moves and highly developed visual style, becomes apparent and he begins allowing style to undermine his stories.

Somewhere around The Royal Tenebaums or perhaps as late as The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, Anderson’s love of his own Wes Anderson-isms, overt and showy camera moves and highly developed visual style, becomes apparent and he begins allowing style to undermine his stories.

Emotional moments were less earned and more forced into existence with a beautifully composed centered slow motion wide shot. Post Tenebaums one might begin to worry that the presumptive heir to Mike Nichols or Hal Ashby was regressing into the creator of weak contrivances, destined to please only those who wanted more of the same.

Moonrise Kingdom, the story of orphaned pre-teen Khaki Scout Sam (Jared Gilman) and his adventures while running away with his socially misunderstood girlfriend Suzy (Kara Hayward), almost has Anderson destroying any emotional viability in the first half of the film.

Moonrise Kingdom, the story of orphaned pre-teen Khaki Scout Sam (Jared Gilman) and his adventures while running away with his socially misunderstood girlfriend Suzy (Kara Hayward), almost has Anderson destroying any emotional viability in the first half of the film.

From the opening shots, we are whip-panned and quirked almost to death. An on screen narrator (Bob Balaban) dressed as a gnome-ish meteorologist explorer warns the viewer of a coming storm. We then blast through a series of introductions and backstory, but unlike the first few minutes of Tenebaums, which is surprisingly efficient with its opening explication, Moonrise Kingdom remains heavy on the explication and light on the emotional content until almost halfway through its 94 minute run time.

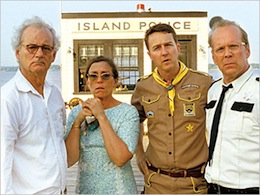

Each of his vast array of characters during the first half of the film are, as always, visually interesting, and even though we can see hints of insecurity in Scout Master Ward (Edward Norton); a loveless marriage between Suzy’s parents, Laura (Frances McDormand) and Walt (Bill Murray) Bishop; and a hidden tryst between Laura and Captain Sharp (Bruce Willis) each character lacks the draw and pull necessary to get us really hooked.

Each of his vast array of characters during the first half of the film are, as always, visually interesting, and even though we can see hints of insecurity in Scout Master Ward (Edward Norton); a loveless marriage between Suzy’s parents, Laura (Frances McDormand) and Walt (Bill Murray) Bishop; and a hidden tryst between Laura and Captain Sharp (Bruce Willis) each character lacks the draw and pull necessary to get us really hooked.

I was just about ready to tap out mentally, when young Sam and Suzy, still on the lam, arrive at a seclude cove.

Here the young Suzy, a music lover who was insistent on bringing a battery-operated record player for her journey with Sam, starts a record and walks out of frame. The waves lap at the beach, the music emanates from the centered record player in Anderson’s stunningly well-composed shot, until finally Suzy and Sam, in all of their awkward glory, return.

Here the young Suzy, a music lover who was insistent on bringing a battery-operated record player for her journey with Sam, starts a record and walks out of frame. The waves lap at the beach, the music emanates from the centered record player in Anderson’s stunningly well-composed shot, until finally Suzy and Sam, in all of their awkward glory, return.

They dance, each trying desperately to look not only comfortable in their skin, but cool. The scene lasts for a few minutes and Anderson holds on that single wide shot for a long time before cutting in close ups. The methodical pacing of this scene allows us to explore the interior space of both Sam and Suzy. The trepidation, tension, and titillation are all visible.

From this scene on, Anderson finally settles down and allows his characters some emotional space, and Moonrise Kingdom transitions into affective ensemble character drama.

From this scene on, Anderson finally settles down and allows his characters some emotional space, and Moonrise Kingdom transitions into affective ensemble character drama.

Throughout the last half of the film it becomes difficult to clearly define whom the main character is, we are so attached to each of them in their own right. There is one conversation between Bill Murray and Frances McDormand’s characters that could be one of the best, most emotionally driven pieces of dialogue that Anderson has ever put to film.

Bruce Willis also has a way of occasionally taking a role in an independent film from time to time just to remind us that he has some real acting chops. Though I do think he was well cast as Captain Sharp, Willis adds real depth and subtly to the character. Anderson’s use of Hank Williams songs when Sharp’s onscreen furthers our understanding of this tragic and loveable figure.

Bruce Willis also has a way of occasionally taking a role in an independent film from time to time just to remind us that he has some real acting chops. Though I do think he was well cast as Captain Sharp, Willis adds real depth and subtly to the character. Anderson’s use of Hank Williams songs when Sharp’s onscreen furthers our understanding of this tragic and loveable figure.

As you can tell, Moonrise Kingdom is something of a mixed bag. If you love Anderson’s previous work, you’ll be very happy with this film. If you’ve been on the fence about his films since Rushmore, then if you can make it through the first half you should be happy with the final half. It more than makes up for it’s clunky and overly structured beginning.

{ 1 comment }

I (somewhat) agree, Trey! I’d say that “Moonrise” is probably Wes Anderson’s most emotionally developed work to date. If he’d straight-up removed Balaban’s nautical elf narrator–who serves no purpose except for quirk value–I think it would have been an even more impressive movie than it already is. Anyway, I’m hoping that “Moonrise” is Anderson stretching his wings a little bit. I’m curious to see where he goes from here.

Comments on this entry are closed.