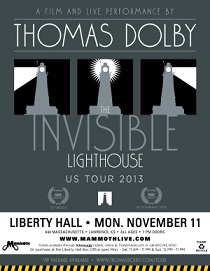

For as diverse a career as he’s had – from “She Blinded Me With Science” to 15 years as the musical director for TED – musician Thomas Dolby has never made a film until now. The Invisible Lighthouse is a personal documentary made almost solely by Dolby that details the closure of a lighthouse on the coast of England near his home in Suffolk.

For as diverse a career as he’s had – from “She Blinded Me With Science” to 15 years as the musical director for TED – musician Thomas Dolby has never made a film until now. The Invisible Lighthouse is a personal documentary made almost solely by Dolby that details the closure of a lighthouse on the coast of England near his home in Suffolk.

The documentary is presented as a transmedia event, with all music, narration, and foley work performed live on stage by Dolby and Blake Leyh as the film plays out onscreen. It’s followed by a Q&A and musical performance. The trailer for the film and performance is a fascinating thing, and looks to be quite the exciting affair when it hits Liberty Hall on Monday, November 11.

We spoke with Dolby by phone last week about the making of the film and its live performance.

The Lighthouse Tour is getting rave reviews.

Yes, it’s been going over very well. I think people didn’t know what to expect from a new kind of paradigm, but it seems to be working out very nicely.

It’s not the first time you’ve worked in what I guess I’d call a sort of forward-thinking nostalgia – your best-known album is called The Golden Age of Wireless.

Yeah, I guess “retro futurism” is the best term for it. I’m fascinated by sort of parallel worlds – what might’ve turned out differently, you know? And, I suppose, on the coast of East Anglia where I live, you’re very aware of that, because East Anglia is the front line every time there’s a war going on. So, you see the remnants of repelled invasions by Vikings and Napoleon and Hitler and so on. It adds a real sense of history to the coast.

The idea of history and the coast is the focus of the film, correct?

The idea of history and the coast is the focus of the film, correct?

Yeah. I’m very strongly influenced by my environment and by the atmospheric conditions. I’ve always written songs about travel, about geography, about history, and environment. I’m not an urban person, and I don’t write relationship songs, really – about text message breakups and things like that – but, yeah, I moved back there six years ago.

It was largely because of schools. We’ve got three school-age kids, and we were in California, where the schools are not too great. I decided to give England a whirl, and it worked out quite well. But, much more than I expected, there was a real sense of homecoming for me. I hadn’t lived there since I was a kid, but I became clear how much it had affected my songwriting direction.

On a certain level, Suffolk has changed far less than most places. The changes are often quite subtle. And, in real terms – the lighthouse on the island, whether that’s flashing or not, doesn’t make a whole lot of difference to our lives, but the fact that I took it so much for granted as a kid was so emblematic of my relationship with the area – which is slowly changing.

And, it’s basically doomed, whether it’s in my lifetime or [my childrens’], or beyond, it’s going in the North Sea. There are lots of villages that no longer exist, up and down the coast, because they’re under the waves now, with a combination of erosion and global warming sort of seeing to that.

In terms of the filming of the movie, did you have others working with you, in terms of camera work, or was it all you? I got the impression of a sort of guerrilla operation.

The lighthouse has an interesting history, and a few secrets in the closet. I really enjoyed getting to the bottom of those, and working in the new medium of film, which is a first for me. I’ve never placed a camera on myself before.

It was pretty much a guerrilla operation, with shaky pans and zooms throughout. It’s my work, apart from some aerial stuff. I have a quadracopter camera that I smashed up a few times – as you do. I think their business model is, they give you the copter, and make their money on spare propeller blades. I thought, ‘I need some help with this.’

Some of the shots, I couldn’t be in the shot and operate the camera at the same time, so I found a guy out in California who’s sort of a god among drone camera operators. He owns a sort of a miltary-grade drone with a big DSLR camera on it, and flies it around with virtual reality goggles. He helped me out on some of the more complicated aerial shots.

But, other than that, I just liked the confessional quality of just holding a camera on myself and just speaking to the camera, almost like a blog. It just worked for me, because it’s a very personal film. It was self-funded – so there wasn’t really a budget for another camera or a crew.

Did it start out with the intent of a feature-length film, or was it just an attempt to document what you were feeling at the time?

I think the latter, really. I didn’t start out with a set plan at the beginning – and, also, I didn’t really have a set date as to when the lighthouse was going to close. I didn’t know whether they were going to dismantle it it, whether they were going to let it fall into the North Sea over time, or open it up to the public. I didn’t really know what the outcome was going to be.

But, I did know that that, among the locals, there was a sort of … collective grief, I suppose, because it had been such a feature of the landscape for as long as we could remember. The flipside is, there’s been ten lighthouse recorded before this one on the island, and the rest of them all fell in the North Sea, so you have a sense of perspective to it.

Lighthouses, their functionality isn’t really there anymore. Ships have SatNav and radar and so on, and the average weekend yachtsman has better navigation on his smartphone than that from a lighthouse. It’s sort of a transitional technology between celestial navigation and modern electronics, but that doesn’t mean that we don’t have a sense of obligation to protect them because they’re so historic and people have such a soft spot for them. They’re so iconic.

I was unable to do anything about saving my own pet lighthouse, but I’ve discovered on my North American tour that there’s 46 lighthouses on what’s called the “doomsday list.” These are the ones that are in immediate danger from either erosion or vandalism or both.

Do you find that the interpretation of the film changes from performance to performance?

It certainly does, because every room has its own atmosphere. We’ve done various shows in arthouse cinemas that are not used to having a theatrical event, with live stuff happening onstage, and some of them have been straightforward music venues. There’s been a lot of different types of venue and, yeah, I find I do it different on different sorts of nights. Some nights, it feels more like a tone poem – it’s more poetic and mesmerizing, and other night’s it’s quite rowdy and many people are responding to lines and applauding after the songs and so on. It’s quite a scope. Quite a difference.

photos: Bruce and Jana

Comments on this entry are closed.