Hey gang, it’s been awhile.

I haven’t written a single piece of film criticism, for pleasure or for an audience, since the early months of 2020. Since then, I have been… in a bit of a strange place. Last time I wrote for you all I have changed my life, my job, my name, and a few other things that feel less important.

We now are seeing perhaps the final film of one of the greatest artists the medium has ever seen. I was moved, because of this, to write short pieces about his work on Facebook, and quickly I found myself pouring out words in a way I had not since I still wrote for this site consistently. I think I’d missed it here. Despite the new name, I feel more myself than I have in a very long time, and I missed writing these things.

So here, gathered in one place, a week of Hayao Miyazaki retrospectives, capped off with a Boy and the Heron review. Enjoy. Hopefully you hear from me again sooner than later.

Day 1: Spirited Away

This movie changed my life more than a little when I first saw it at age seven. I had never seen a movie that felt so emotionally evocative and fulfilled, so fully, the very specific feeling I had as I grew up. The first time I saw it, I almost felt like it was a dream I lived with, until further viewings showed me parts I was sure I made up were in fact in the film.

Moving between stages of life can feel like being thrown into an alternate world. The people around you change, the actions that seem routine one day can feel distant the next, you assume new identities. The idea of finding yourself in a new environment with a new name is extremely resonant to me. Shocking, I know.

Chihiro’s journey through the film is marked by two things: the kindness of strangers, and the necessity of adaptability. Throughout the movie, various spirits go out of their way to help Chihiro, and give aid, no matter how small. From the obvious massive actions by Haku that drive the plot, to Kamaji’s willingness to lie, to the Radish Spirit simply taking her up the elevator, Chihiro is shown that she is able to find help even in the darkest moments, even if the help seems somewhat minimal. While you cannot purely rely on others, looking for aid is never shown as a hindrance or as taking away from her agency. This, too, ties into Miyazaki’s Shintoism, showing the spirits as often helpful and kind, even if their intentions aren’t always clear. No Face is my favorite example here, as his actions clearly show a fondness for Chihiro and true willingness to help, but a wariness of taking his help blindly and returning said kindness without thought clearly leads to danger. This subtlety is rare in media for children and it’s a lesson I’m still trying to learn.

The other element, the need for adaptability, is also resonant. Chihiro picks up many skills on her journey and needs to act thoughtfully and quickly. However, if she bent herself fully to her new environment, she would be lost to it, shown through her forgetting of her own name. One has to adapt to their world, and act with the bends in the river, but they should not fully allow themselves to be taken away or else they lose all agency.

My favorite sequence, growing up, was the train ride to Zeniba’s house. The gorgeous sequence through the shallow sea was the first scene I’d ever seen that was so quiet and contemplative, allowing me to just feel the emotions I’d felt, build up my preparedness for the final act of the film, and think through what brought us there. These scenes of quiet are slowly disappearing not just from kids animation but from all film, seemingly, and I’ve always yearned for another moment like it. When I was forced to take the train back to school from St. Louis my freshman year of college through a snow-covered Missouri, this scene came to mind a lot.

Spirited Away is a film I don’t like talking about a lot because it is clearly good, in ways most people agree on. One doesn’t add anything to the world by simply saying “Spirited Away is good”. But it is. And it’s been one of my favorite films for a very long time.

Anyway, hope you enjoyed this, I’ll get more concise as these go along.

Day 2: Kiki’s Delivery Service

I’d be lying if I claimed Kiki’s Delivery Service was always one of my favorite Ghibli Films. Bald-faced lying. Growing up, while I enjoyed it I always found it rather slight and unserious, especially compared to my favorite Miyazaki projects. The animation was gorgeous and the narrative had propulsion but was it any part the equal of Princess Mononoke? Obviously not.

This year I’ve changed my view rather drastically. Something about a young woman, upending her life, setting out on her own, living alone, barely making enough doing menial work to survive on just pancakes really resonated as I upended my life, set out on my own, lived alone and barely made enough to survive on just pasta.

Strange how that works out.

I’ve watched it like 8 times this year alone. It makes me cry every time.

A few of Miyazaki’s major preoccupations are on display here, but more than anything else are two of his loves: flight and Europe. The city here, largely based off Stockholm and Visby in Sweden with healthy doses of Bruges, Copenhagen and Florence for flavor. Miyazaki’s visions of Europe (perfected here and in Howl’s Moving Castle) are particularly fascinating to me as I’ve always found the narrative of “it’s like an inverse of Orientalism” rather insipid. Plainly, the man has a firmer understanding of Europe than most Western Authors have of Japan. The taste in architecture, the positions of important buildings, the steady appearance of small townships, the baking UGH the BAKING clearly shows an affinity and awareness of Western tastes that doesn’t wash the hands of Weeb Americans as much as they’d like,

The flying is the other kicker here. There are few things in the world Miyazaki loves as much as his flying machines, which we’ll be getting into with later entries, but there is no depiction of flight itself as revelatory and freeing as Kiki’s own, and her struggle with depression shown as a struggle to maintain her flight encapsulates perfectly what Miyazaki seems to find inspiring about the act. Flight is freedom, yes, but it is also joy. In musicals, characters sing when their emotions are too strong to speak. In Miyazaki, they fly.

I also want to highlight, once again, the kindness of strangers. Obviously Osono and her himbo baker husband provide Kiki give her housing, there is the Madame who shows her affection, and there is Tombo who gives her affection and friendship (mm I relate to the girl who found a bespectacled cutie who thinks she’s amazing weird), my favorite example here is OBVIOUSLY Ursula and not just because I want to be her. Ursula’s biggest contributions to Kiki’s life are less her literal aid, than something spiritual. Sometimes we need someone to look up to, who has done what we have and gotten through it. Ursula, alone in her cabin making incredible art, may not be a practicing witch, but she is still something to love up to, and a way to actually look forward to your future when times are hard.

Sometimes, you need to upend your life. And you’ll get sick, and run out of money, and go through bouts of self doubt and depression. But at the end of it, you may still be able to make great art, or find someone who likes you, or rediscover your flight.

Day 3: Castle in the Sky

The first official Ghibli film is often overlooked in the states. Not quite one of the pastoral kids films that capture the imagination, nor one of the hard-edged adult epics that get the critical acclaim, a lot of us here in the West don’t seem to know quite what to do with this fantasy adventure film. Part of this may be due to the English dub, which due to a miscast James Van Der Beek is one of the only ones that doesn’t either match or even exceed toe quality of the original Japanese, but part of this too may simply be a misunderstanding of the film. A lot of dissections of the film approach it as a classic 80s style dark fantasy kids film. Which it is, to an extent.

A more compelling discussion of Castle in the Sky, though, may be to treat it as the keystone in understanding Miyazaki’s philosophy. His feminism, his environmentalism, his anti-capitalism and his deep respect for children are all on display, fully formed. Because it is one of his earliest films it is treated as though it is still a rough draft, “early Miyazaki”, ignoring the solid twenty years of contract animation, manga production and tv work that came before. Castle in the Sky is not a rough draft of greater projects to come, it is a major work of animation and one of the best Japanese films of the 1980s. Full stop.

A lot of what I love about this movie is its magic trick of straightforwardness. It contains Miyazaki’s most straightforward villain, his most rip-roaring adventure plot, and the clearest explanation of his views on the intersections between technology and nature. We are walked through the mining of Aetherium, the advanced technology of the Laputans, the descent of the city and its ilk into the Earth, the reclamation of nature and the single-minded greed of the military. We get a comedy troupe of pirates and clear, exhilarating action scenes. These things are all so incredibly straightforward, they trick you into falling deep into its incredibly subtle worldbuilding and sophisticated politik. And I love it.

Nobody, not Muska, not the miners of the land, not Pazu’s father nor Sheeta’s grandmother, knows as much as they think about Laputa. We as an audience even see clearly that some of what is “known” is wrong, as Muska spends much of the film treating Laputa as a Utopian, Iron-Fisted and singular force, when in the opening credits we see clearly it was but one of hundreds of flying fortresses that once filled the skies. Whoever built the flying city and the robots that inhabit it are so far gone that we can only speculate as to what their original intentions were based on legend, oral history and the rare engraving. Clearly these people both cared for beauty and nature, but also were ready for devastating violence. We CANNOT know the true intentions and culture of these people. They have simply been gone too long. There is not a throne room, just a tomb.

I think there’s a reason why a lot of game developers have found inspiration in this film. Shadow of the Colossus, Elden Ring, Tears of the Kingdom ALL share DNA with this movie, and astute viewers would likely be able to find even more places media has taken from this underrated project. The basics of environmental storytelling abound, and while we can clearly see various elements of the narrative, none of it gives a full picture and we must put it together ourselves.

Castle in the Sky SHOULD be (and in Japan IS) treated as one of the major works of Miyazaki’s oeuvre. It features some of his best animation and one of his most inviting narratives while also playing a surprisingly subtle game thematically. The first two entries in this series were me speaking from the heart, so here’s my personal message about Castle in the Sky.

STOP SLEEPING ON THIS MOVIE! And remember, all good pirates listen to their mom.

Day 4: Princess Mononoke

Lady Eboshi is not a villain, but she is still wrong. This fact is VITAL to any accurate reading of Princess Mononoke, and by proxy the whole of Miyazaki’s whole ecological ethic. She is not a villain. She acts on the needs of her community, she has built a utopian society removed from the collapsing Shogunate System, and she only commits to violence as a method of protecting those she serves, or improving their lives. She is, however, still wrong.

Where Castle in the Sky and other works depict Miyazaki’s sadness at the loss of natural spaces, Mononoke’s presiding emotion is rage. It is the rage of San and her wolf family, willing to kill every citizen of Iron Town if it meant the destruction of the forest would stop. It is the rage of the women of Iron Town, who fought so hard for autonomy and freedom from their oppressors, only to have their husbands killed raiding for resources. It is the rage of Ashitaka, cursed and forced to leave his village, seeing the pain that the violence of all parties involved has caused. And, of course, it is the rage of the Nameless God of Hate, infecting the bodies of the Gods of the Forest, destroying everything in its path. This rage is unavoidable, and natural. One must strive to contain it, but it is impossible to completely recuse yourself from it. When the world is cursed, rage is inevitable.

Iron Town is my favorite illustration of technology’s impact on humanity in film. Period. It is not inherently evil, it has given autonomy to the women of the forge, it has given agency to the lepers who build the guns, it has freed all the citizens of the township from a destructive cycle of civil war and raiding that marked the Edo Period. But it still destroys the natural world. It is not technology itself causing these problems, but the misguided actions of those using it. With a steadier hand and more empathetic approach to nature, technology could exist harmoniously with nature rather than be in conflict with it. But, in our most desperate moments, it is difficult to act with such tact.

Also vital in any reading of Princess Mononoke is the fact that Ashitaka is of an indigenous background. The Emishi, named after a now extinct ethnic aboriginal group in Japan distinct from but similar to the Ainu, in this context represent indigenous peoples as a whole in times of climate crisis. The peoples who had the least to do with the creation of the crisis are the very same left with the least resources to survive it. There is a reason why it is vital, today as we prepare for seismic changes in our ways of life due to climate change, that we look to the indigenous peoples of the world, as they have been forced onto the most inhospitable of land and left to fend for themselves. Ashitaka’s role, as one of the last of a dying clan, is to show that a middle path between luddism and unchecked progress exists for those willing to find it, and how it often requires an indigenous point of view to see this perspective exists.

I’ve been working hard to make it clear that rankings of Miyazaki’s films are, inherently, silly and arbitrary. His work comes together as a coherent whole, and placing one film atop the rest denies the brilliance of his body of work when viewed as a whole. THAT SAID, if I were to pick a single project to call his opus, it’s Princess Mononoke almost every single time. Princess Mononoke is, functionally, perfect. Not a note or line or shot out of place and it is a burning, staggering message that resonates only more and more as we see more and more effects of our actions on the survivability of this planet.

We must never accept defeat. Rage and despair will be inevitable. But we can fix our world. Just because the world is cursed does not mean we must give up.

Day 5: Porco Rosso

I’d much rather be a pig than a fascist.

Trust me, I’d rather do a write-up of My Neighbor Totoro today, in light of how dark the last entry got and how dark the next two will be. But how the hell do you ignore the film that gives us THAT LINE? When in film history has anyone put so bluntly and plainly the repugnancy of Nationalistic Chauvinism than right there. The line works in both English dubs and the original Japanese, it’s simply magical. I want that line tattooed on my back like a tramp stamp. I love it so much.

But that also forces us to ask, WHY would Miyazaki, who while not sparing in his general gestures towards environmentalism and working class solidarity but so far was becoming very successful with fantasy adventures for children, decide to step that directly into politics? Well, because it’s the right thing to do.

So let’s break some things down. First up, why is the film set in Italy? Well, for the same reason America likes setting its anti-Imperialist films in space or in Medieval Europe: if we set it in the US the anti-Imperialist message might cut too close to home. Watching one coastal axis power descend into fascism in ways that would be remarkably easy to repeat was easier for Japanese audiences to digest than watching their own former coastal axis power descend into fascism.

Second, why does Miyazaki make this political message in a youth friendly fantasy adventure? Two answers make sense here. One is that it puts more butts in seats. The other being the same reason Mel Brooks had his fascists singing and high-fiving, or Taika Waititi had his play silly boyhood games of strength. Fascism thrives when uncritically viewed as powerful or cool, whether or not it’s evil. But when it looks silly? Makes recruitment rather difficult. Neo-nazis reclaimed “Tomorrow Belongs to Me,” but they couldn’t reclaim “Springtime for Hitler.”

The film has a LOT more empathy for pirates than fascists. They may be greedy and silly, but they still stand against authority and bigotry. It has a lot more still for the ridiculous and bloviating Americans. Donald Curtis may be self-aggrandizing and over the top, but he still believes in individual autonomy and thinking outside of the box. And still more, it has even more for its women, whose role under a fascist system would be nothing but mothers and nurturers. Miyazaki’s women have always been fabulous, and he revels in showing feminine strength viscerally and honestly. What is lovely about Porco Rosso is that when a man (or pig) takes front and center, the strength and ingenuity of the women around him almost is a given. We don’t need to know how Fio is such a brilliant mechanic, or the women of Milan can put his plane back together, or whether or not Gina is actually reading every man who enters her bar correctly. They’re all singularly brilliant, they’re Miyazaki women. Why would it be any different?

This film and the one I’ll cover tomorrow share a LOT of DNA. The blunt disgust with fascism, the love and joy for flight, the almost amused side-eye toward economic upheaval, and the fact that Miyazaki’s original manga for both featured talking pigs (kept here but omitted for the later film). Miyazaki generally tends to keep his preoccupations around for some time.

Miyazaki himself has also discussed his love for this film for autobiographical reasons. To him, Marco Rossolini is his clearest self-insert avatar. A gruff, cynical old man, always in sunglasses and chain smoking, mocking his own appearance and thumbing his nose at the idiots who attempt to run his country. He has a chauvinist streak of his own, but he knows it, and he’s endlessly aware that the young women who now surround him are likely more talented and self aware than he will ever be, even as he oggles them. The fact he sees so much of himself in the character is so telling, and I love it.

I think, then, the reason I cherish Porco Rosso so much, is that it gives a way to approach the darker, sadder elements of Miyazaki’s work in a way that’s still rip-roaring and fun. This film is hysterically funny to this day, and the action scenes are sharp and exhilarating. While his other explorations of authoritarianism show his disgust more viscerally, in no other place can you just sit back and laugh in the face of how those asshats bend themselves to appear so strong. You don’t even need to argue with these people, it’s pointless. They’re wrong, just make fun of them. It’s easier that way.

I’d much rather be a pig than a fascist.

Can’t top that.

Day 6: The Wind Rises

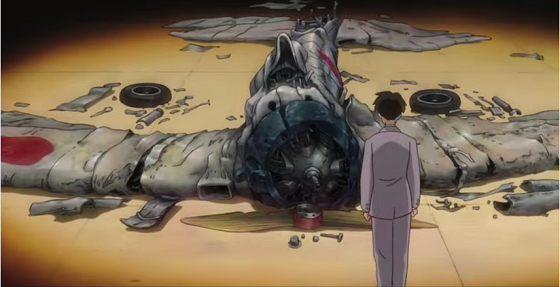

The Golden Age of Flight was a revelation. An explosion of technological advancement, it was one of the rare, beautiful moments when technology and art came together in beautiful union. Aeronautical Engineers had less in common with today’s efficiency obsessed tech gurus than with the occasionally insane, artistically minded Physical Philosophers of the Enlightenment, and today their machines still stun in their beauty and inventiveness. The beauty and life of these machines is illustrated through my favorite aesthetic element in any Miyazaki film, the human voices that create the sounds of the propellers and engines throughout the film. The planes, here, are living, breathing, human creations. Holy shit what a move. It shows what promise the machines had, and how fun and brilliant bits of engineering they were.

Then came the world wars, and forever flight would be driven, first and foremost, by those designing weapons of war. We are forced to watch as Jiro’s own planes are used to pummel the Pacific into the dirt, as the designer himself is left unable to stop the onslaught.

The Wind Rises is a tragedy. Fully and completely. It is at once Miyazaki’s most beautiful and poignant statement on art as a whole, as well as his most distraught and nihilistic indictment of war and violence. Once again, I find myself wanting to urgently make clear to what few people are reading this, do not overlook this film. It is a MAJOR work of Miyazaki’s, and one of the best films of the 2010s.

Perhaps it’s important for me to address why I believe this, especially when the film is a glowing portrait of the man who designed the most famous weapon of one of the most disturbing and deadly Imperial regimes in the history of the planet. Western audiences, largely only lightly familiar with how to read this film, have decried the film as war crime apologia or simply naive. I am flabbergasted by those people, as simply that proves to me a lack of basic media comprehension.

Death is a constant shadow over the film, from the very first moments Jiro is burdened by dreams of living, breathing bombs that seem to spew smog. As we leave the Taisho Era and move into the beginning of the Showa, the number of military officers begins to rise, and suddenly the beautiful flying machines of the first act begin to be adorned with the rising sun. Jiro himself, notably, never finds himself caught in the Nationalistic furor of his nation. He is driven by the art of aircraft, not by Imperial ambition. It is here that the horror hiding behind the film becomes clear.

I think it is notable that in the original Japanese, Jiro is voiced by another great Japanese animation director famous for fantastical visions that ride the line between hopeful and deeply horrid, Hideaki Anno. Anno’s own work saw great commercial success and influence in more conservative, militaristic markets, all while he attempted to rebel against the very system that gave him success. I wonder how much Anno relates to the plight of a great artist whose work is used to justify bloodshed.

Many folks latch onto the romance of the film, which is understandable. The heartbreak is palpable and it makes for a compelling final act. However to me, it largely serves to outline the tragedy that is the death of the Golden Age of Flight. Just as Nahoko passes, so does the hope that flight may ever return to its looser, less militaristic past. His fighter is born the same moment Nahoko leaves his life forever, and the devastation his fighter causes is shown in near exact imagery as the aftermath of the Kanto Earthquake. As Jiro dreams of a more hopeful future, we must live with the knowledge that said future likely may never come, and we must accept the terrifying, violent present instead.

In Japan, the film was controversial not for historical revisionism (because there isn’t much), but its willingness to depict the Japanese War Machine as a force of evil. The shift from the Taisho Era to the Showa is shown as nefarious, where though the wealth of the nation improves, the autonomy and health of its citizens is cast aside. As the world veers towards strong man conservatism, it is those who fight for beauty and joy who are truly rebels, and we can only hope they succeed in some small way. Joy should not be seen as weakness, it is an act of resistance in a world that continually teeters toward annihilation.

I think The Wind Rises was a film Miyazaki needed to make. As the medium he dedicated himself to became more and more commercialized, and his own health deteriorated more and more, he needed to make a film that both looked his fears in the eye, as well as reminded himself of the hope he still fought to keep. Growing up in his father’s factory, watching instruments of the Zero come into being just to see them used in the slaughter of thousands, he maybe needed a more direct expression of his conflicting love of the flying machine. The Wind Rises is a wonder and I wish its reputation was more than that of “the boring one”.

One thing I want to add before posting, the film is actually dedicated to two people. One is, of course, Jiro Horikoshi, the film’s subject. The other is Tastsuo Hori, acclaimed translator and poet, whose novel The Wind Has Risen bore enough similarities to the real life of the great aeronautical engineer that Miyazaki took many of the lines and visual motifs for the film from the novel. Hori was also, notably, the man who translated Paul Valery’s The Graveyard by the Sea into Japanese, the same poem the characters are so moved by in the film. Felt like that was worth noting.

Day 7: Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind

From the penultimate film to the first (yes I know about Castle of Cagliostro but I’m talking original projects, c’mon do we really count that?)

Nausicaä, more than any other film of Miyazaki’s I think, creates a cult-like adoration. Other films are more popular or more discussed, none are as much of a “default favorite” by as many people as Nausicaä. No face tattoos could be on anyone’s arm regardless of how much they actually care about Miyazaki. An Ohm tattoo? That means something.

I think the film has this pull on people because it feels like a genuine recipe for hope when it seems like you’ve already lost. In Mononoke, the world may be cursed, but it’s still alive. The spirits of the forest still exist, at least.

When Nausicaä begins, the world has already fallen. Humanity barely stays alive on the fringes of the world, having burned it all up with nuclear weapons and pollution, and the fungus and insects that were the only things that could live on these pollutants create the only true natural spaces left. At a time where we are training parasitic worms to eat plastic, this note feels prescient.

Our planet has reached 1.5 degrees celsius mean temperatures above pre-industrial times. We have breached the goals of the Kyoto Protocol. Within my lifetime, the ice caps will melt, the tipping points will be reached, and countless ecosystems will be thrown into chaos. Humanity will need to adapt fast in order to not descend into squalor, to maintain what ecosystems we can for our survival and the survival of the creatures that surround us, and maintain the survivability of our planet.

A common misconception, I’ve noticed, is that many of my peers seem prepared for the world to end and humanity to disappear. Far more likely, it seems, is the society of Nausicaä. Small societies of humans with mixed levels of technology scratching together climate havens to protect themselves from the flames. If we do not fight now to mitigate the worst effects of climate change, a new, harsher, darker world order is waiting for us.

I think it’s notable the number of trans women I’ve met who name themselves Nausicaä. There is an awareness of mortality that comes with transness that leads one to contemplate the mortality of our world as well. Whether it be the depression that comes with living in the wrong gender for so long, the bleakness of the current social climate for those who do come out, or simply just how much transitioning forces you to contemplate your own body, death is frequently on the mind, and with it societal collapse.

The idea of being Nausicaä, who can speak to the Ohm, who can unite the People of the Valley of the Wind and Pejite, who can bring humanity together again and return it to some kind of hopeful future, who cleaned the water and tilled the soil, is the most incredible thing. It is not in the violence of the God Warriors or the machinations of Pejite or even the conservatism of the Valley that humanity again thrives. It is through progress, empathy and compassion.

The people who love Nausicaä LOVE Nausicaä. It’s a film that creates lifers, people who use it to help guide their moral ethic and define what hope means to them. It implies an awareness of the hardship ahead, and acknowledgement of the chance of failure, while also standing firm and holding out hope nonetheless.

This project has been exhilarating for me. This is the first film criticism I’ve written in several years, and it’s been so joyful to be able to flex this muscle again.

Miyazaki is one of my all time favorite artists. His work means an immeasurable amount to me, and they give me comfort and joy when my days are the bleakest. If The Boy and the Heron is his final film, I can only hope we treat it with the reverence and care it deserves. I hope reading these has been enjoyable, thank you so much for reading along.

Day 8 (because The Boy and the Heron required more time): My Neighbor Totoro

So, like, I HAVE to talk about Totoro right? The masterpiece of his children’s films, the film that forced anime into the West, the most comforting and homely film maybe ever made. The animation hasn’t aged a day and the story still can pull delighted giggles from any audience. Plus it has Catbus!

I briefly thought I wouldn’t have that much to say about My Neighbor Totoro. Not because its a kid’s film, to be clear, but because most of what I’d wish to say is discussing nostalgia, talking about the “countryside summer” that is so romanticized in Japanese thought and literature. To do so, I would likely be simply plagiarizing wholesale game critic Tim Rogers’ Action Button Review of PS1 classic Boku no Natsuyasumi, one of the best pieces of writing ever put on the Internet, and I’m not so dishonest to claim one of my favorite writers’ work as my own.

However, I do believe I have something to say about this film, and it’s about how genuinely incredible it is in its manufacture. It is gorgeous, with care and attention poured into every frame. Why is this worth noting? Well, because this is the most kiddy of kids’ films Miyazaki ever dreamed. It is cute and comfy with a singalong theme and cute kid characters. While there are hard emotions, there is still a happy ending and most of the runtime is dedicated to small adventures and sisterhood.

My Neighbor Totoro is a cozy, cutesy kid’s film. It is also a full tilt masterpiece and the OTHER film I point to as Miyazaki’s opus when I’m tired of talking about Princess Mononoke. Miyazaki poured his heart and soul into this film and created what is, for my money, the greatest film about childhood FOR CHILDREN ever made.

Miyazaki has great concern about and for the future. Throughout his oeuvre, war, authoritarianism, climate change and violence fill his thoughts. He is scared, and I get why.

He clearly thinks hope and environmental concern are ways toward a brighter future, but if Miyazaki has any theme greater than those (or even his flying machines), is his respect and care for children. Every film of his shows his trust in the intelligence and ingenuity of the next generation, and tries to show the need for children to explore on their own.

My Neighbor Totoro depicts Satsuki and Mei exploring the world on their own, without supervision, and learning new ways to see and understand their universe. The most exhilarating moments of the film are not battles or giant pieces of magic, its finding tadpoles in a puddle, learning how sprouts grow or riding a Catbus. I really like Catbus. We should all really like Catbus.

His approach to children is careful, but fully respectful. They are peers who can find things on their own. They need parents who are invested in them, but do not need constant supervision. They need to be able to make their decisions and learn about the world in their own time.

The environmentalism is there, we could talk about this being the clearest Miyazaki has been about his Shintoism, there’s a throughline again of feminine strength, but it is VITAL we sit and live with Miyazaki’s respect for kids. THIS is why he makes art, so that the next generation may have images that help them learn the lessons they will need later in life. Miyazaki has described The Boy and the Heron, for instance, as a message to his grandchildren saying “Grandpa’s preparing for the next world, here’s what he has to say to you”.

Miyazaki’s greatness isn’t just in his technical acuity or his dissections of Big Ideas. His work is also joyful, and educational, and can guide you through life. We have been lucky to live in a world with his work, and I cannot wait to see how much more his work means to me as I continue to change, grow and learn about my world.

Show My Neighbor Totoro to your five year old, then go play in the forest with them. Show your seven year old Kiki’s Delivery Service, when they complain about having to go to school, so they can know how important it is to persevere. Show your ten year old Spirited Away so that they can start the process of accepting change in life, and then show them Porco Rosso so they can see what changes to accept or reject. Show your twelve year old Howl’s Moving Castle to show them the dangers of the world and the joy of other people, show them Mononoke at 14 to teach them to care for our planet, show them Nausicaä to help them never give up hope, and hopefully when they are older, watch Wind Rises with them so that the two of you may wrestle with the ways the world has changed, whether or not you wanted it to.

Finale: The Boy and the Heron

Earlier this year, Game Studio Arkane (the company that produced critically acclaimed immersive sims such as Prey, Dishonored and the exhilarating Deathloop), released the co-op vampire shooter Redfall. Redfall released to a critical thrashing, poor sales and a myriad of bugs, leading many to question whether the studio was beginning to lose its magic.

As it turned out, the production of Redfall was spurred largely by Arkane’s Parent Company’s new ownership, Microsoft. As much as 75% of the dev team responsible for their classics had jumped ship during production due to disagreements with direction and poor working conditions under new management. Most of the final product was put together by a ramshackle group of younger devs, contract employees and recent game design graduates, none of whom had the experience of those they replaced, and most willing to take the poor pay that came with it. While the studio itself remained near unchanged, without the devs in question, what does it even mean for Redfall to be an Arkane game if the vast majority of the people who made up “Arkane” were gone?

Something I’ve always disliked is that we talk about wanting to go see a Ghibli film. What’s your favorite Ghibli? Does it have that Ghibli magic? But gang, Ghibli is just a company. Companies don’t make art, people do.

Dishonored wasn’t made by Arkane, it was made by Raphael Colantonio, Harvey Smith, Viktor Antonov, Sebastian Mitton, Terri Brosius, Austin Grossman, and many other programmers, developers and artists who poured themselves into the game. The Classic Warner cartoons weren’t made by Warner Bros. Studios, they were made by Friz Freleng, Tex Avery, Bob Clampett and Chuck Jones. Et cetera, et cetera.

These films weren’t made by Ghibli. They were made by Isao Takahata, Joe Hisaishi, Toshio Suzuki, Takeshi Seyama, and, of course, Hayao Miyazaki. People leave the world with the art they make, and are remembered by the images they blot into our lives, the company merely sells it to us. We need to celebrate our favorite artists by name, and with real support. That can start with easy masters like Miyazaki, but we need to treat every artist like this.

Why do I begin my discussion of The Boy and the Heron with this polemic about accreditation? Because, simply, for the first time in his many claims he has plans to do so, Miyazaki feels as though he is actually saying goodbye.

Spoilers ahead.

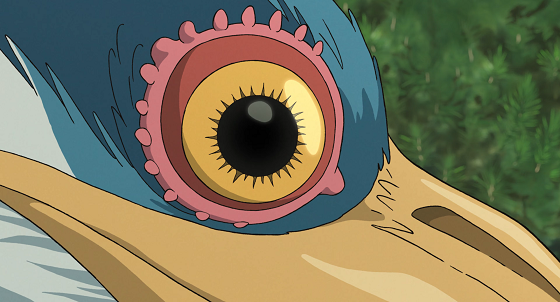

There are two Miyazakis in The Boy and the Heron. The first, a boy, Mahito, brought to the country during the height of World War Two. His father runs a factory building Zeroes to be sent to the front, and his mother was lost before his eyes in a horrifying hospital fire. He is doted on by lightly magical feeling old women, and he is tormented by a mischievous gray heron. Said heron calls to him, attempting to sucker him into coming into the abandoned tower on the edge of the boy’s new estate. For those who’ve read my pieces thus far, and those familiar with Miyazaki’s autobiography, all of this will sound exceptionally familiar.

The reading of The Boy and the Heron from Mahito’s perspective is one of Miyazaki reflecting on childhood and the changes of life. It is also a fairly direct dressing down of the Imperial Japan he grew up in. As he came into manhood, he bore witness to his home country corrupt itself, drawing Western Influence in and raising the profile of fascists and sycophants hoping to rule the world. The birds of the old Granduncle’s world are stand-ins for the Imperialists of the Japanese Rising Sun. Old noble Pelicans, once robed in quiet power, now left fighting children and reaping destruction far below their standing, far more lowly than they deserve. Parakeets, tittering and silly, play-acting strong armies and kings, waiting for the first moment they get to cannibalize the world and prove their strength. I cannot tell you how happy I am I leaned into the antifascist angle with this series because I rode that stock to the fucking moon. Militaristic fervor is shown as little more than the insipid power plays of silly, colorful, shit-producing birds.

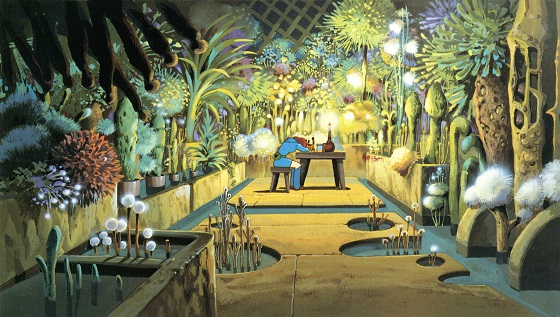

The other Miyazaki is the Granduncle himself. An ancient wizard, with wild hear draped in black, gazing upon his kingdom of magic and mystery, surrounding himself with valiant but silly servants, waiting for his true successor to build a better world. When the child shows that a new world must truly start anew fully, and be discovered rather than forced, the old man happily allows his empire to collapse. This is depicted as the gorgeous tower of the real world falling in on itself, and the magical kingdom disappearing from the cosmos.

I would like to point out, to those who keep claiming Miyazaki will never retire, that an old man letting his world die is fairly potent imagery for one uninterested in stopping.

The Boy and the Heron is spectacular, and both wildly accessible and fully oblique. Much of its imagery is draped in symbolism far denser than his previous works, and he seems less interested in explaining the magic contained. This has resulted, though, in his most magical feeling film to date. It feels murky, mysterious, as though you’ll find an unexpectedly deep pool at any time. Much of the imagery and theming also demands a knowledge of the rest of his work, and asks a viewer to draw connections to where his other films have taken these images. What do magical girls mean in Ponyo or Kiki? Or the strong women living on their own? When have we seen noble animals at the end of their life? Or the devious, outsider tricksters?

Is the fundamental European-ness of the Tower and Granduncle’s world a sign of limited Imperial Imagination, or a reference to the role of European Art and Literature on Miyazaki’s psyche? When the gray heron pops out of his feathers and shows his human face, how much stock should we put into his similarities to Porco Rosso or the monk from Mononoke?

And goddamn, all this bird shit is hard to animate isn’t it? If Miyazaki is the granduncle, is he accusing the rest of his peers in the anime community of being sycophantic, shit spewing bird brains?

I mean, kinda yeah. But this is the beauty of The Boy and the Heron, this is the most Miyazaki has ever played in the realm of poetry. The film’s imagery is there to evoke ideas, themes and meanings, force you to metafictionally bounce between it and the rest of his work, other works of Japanese literature, history itself and his own autobiography. He is not telling you how to interpret it, because that isn’t the point. He invites you to contemplate this work, and the rest of his filmography, as he waxes poetic about the malice required in the building of worlds, the strength of womanhood, and his mixed fear and hope for the future.

It is impossible to fully rebel from the previous world without malice, try as we might. Just as Miyazaki threw out Imperial Japan’s militarism, fascism and chauvinism, he knows his own system must be thrown out as well. He seems aware that the world his generation created has led to environmental collapse, mass migration and the destruction of cultural norms. It’s hard not to think not only of the last of the samurai with the Noble Pelican, but also the struggles real seabirds have finding food and shelter as the seas warm, fisheries empty and storms throttle our shorelines.

Several friends have been looking to me to decode The Boy and the Heron but it feels somewhat inappropriate to do so. I mean, yes, I need a handful of more viewings before I can speak as authoritatively as I do with his other films. But I almost want to keep this film mysterious, dark and poetic.

Spirited Away changed my life more than a little when I saw it for the first time. It was strange mercurial and scary, and unlike anything I’d ever seen. God, what joy there is to have the master give me another film that makes me as scared, confused and excited to see the world. I cannot think of a better ending to his works. Thank you.

Comments on this entry are closed.