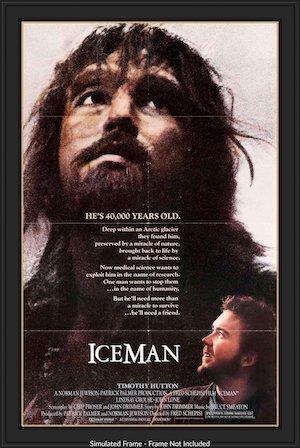

Iceman, written by John Drimmer and Chip Proser, directed by Fred Schepisi, hit theaters in the spring of 1984. It’s a quiet, contemplative sci-fi drama about a perfectly preserved prehistoric human discovered in the arctic and it made a little over $7M at the box office, garnering modest praise before fading from memory. Even now, its pages on Wikipedia and Rotten Tomatoes are curiously barren.

Trapped in a block of ice, the 40,000-year-old specimen is miraculously resuscitated as the film opens—a science-fiction setup that’s almost purely logistical. For that reason I’m not really interested in dwelling on the genre question. The film is technically science-fiction, and it’s often the case that the best examples of that genre defy conventions. But the reality is that the sci-fi aspect here serves as a springboard for a story about the past, and so it’s the past I’d rather focus on.

Less than a decade after the film’s release, the remains of what’s come to be known as “Ötzi”—Europe’s oldest natural mummy—were discovered by a hiker in the Alps (a stretch of them, in particular, located on the historically-contested border between Italy and Austria). Mummy being the operative word. The specimen in this case was not frozen, unchanged, but his body, his clothing, and the possessions he carried at the time of his death were all nevertheless remarkably preserved. His death was first assumed to be the result of exposure until his injuries and toolkit were examined, basically presenting a picture of a violent life that met an equally violent end. But like the genre question earlier, I’m not really interested in how he ended up there.

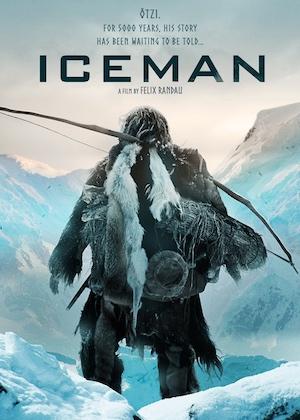

Iceman, a German-Italian-Austrian co-production, written and directed by Felix Randau and released in 2017, offers a decidedly cinematic interpretation of that man’s life, whoever he was, and the tragic course of events that led him to die there in the snow.

People wonder why there are so many movies and shows to come out in recent years set in the 1980s, and I think, aside from pure, shameless nostalgia, a major reason for that particular trend is that the 80s roughly marks the tail-end of a kind of romantic, pre-internet sense of loneliness that’s especially useful to storytelling. Stories about missed connections and great distances took on a graver, more poetic dimension than is even possible in a contemporary setting.

My 10-year high school reunion came and went a few years back, and, as far as I know, almost nobody showed up. Maybe a couple dozen people out of a graduating class of over seven hundred. If asked to explain it, I’d feel pretty confident in saying it’s largely a function of social media having simply obliterated any sense of mystery concerning the people you used to know. They’re almost always accessible to you now. What’s the point of a reunion in the face of that? It’s a little demoralizing to consider, but our lives have become less dramatically compelling in a lot of ways because the kind of loneliness that we experience is, more often than not, simpler to solve in practical terms and decidedly vista-free.

A sea voyage is more fraught than an international flight. Miles of distance between family and friends and years between points of contact is inherently more dramatic than a missed call. And a phone ringing in an empty house without caller ID to make sure you know it happened has greater stakes than a log of missed calls and follow-up messages, the device receiving them with you at all times. I’m not making a judgment about it one way or the other. I yearn for the dreamy solitude of my 90s childhood and am simultaneously grateful for easier access to the shit I consume. It is what it is.

In Iceman (1984), John Lone gives a powerful, committed performance as “Charlie” (an approximation of his stated name, Char-oo), a man separated from the people he knew and loved by tens of thousands of years. The plot machinations driving the film forward concern Timothy Hutton’s anthropologist’s attempts to shield Charlie from inhumane experimentation (some version of euthanasia and dissection, possibly something worse), his conviction that the world’s loneliest man deserves dignity and autonomy. The film raises its share of ethical questions concerning the “civilized” world’s intrusion into the cultures outside of it, the morality of constantly seeking to extend the human lifespan, religious liberty. Aside from a brief discussion of the (bullshit, non-) issue of overpopulation, all of this stuff remains relevant. The rest of the cast, including Lindsay Crouse, David Straitharn and Danny Glover, are all good, the arctic base coming across as thoroughly lived-in and authentic. But it’s Lone’s performance that makes it work, and his relationship with Hutton.

In 2017’s Iceman, the central character known to us as “Ötzi” (“Kelab,” Wikipedia tells me, in the film) is the chieftain of a small clan who, after returning home to find his people slaughtered, the mysterious religious artifact at the heart of their community stolen, sets out for revenge. His journey, imperiled and violent and full of scenes of basic survival, calls to mind something like The Revenant, and meets the challenge with smooth, assured camerawork and stunning locations. Early in the film we see the painful birth of a clan member and the immediate natural death of its mother, a set of somber funerary rites in a nearby cave. I can’t claim to be anything more than a layman on the subject, but all of this comes across as thoroughly researched and highly plausible. All it can ever be is speculation, after all. But at the very least, in terms of costume and hair and makeup, Kelab is a near-picture-perfect realization of what’s knowable about the real person, and Jürgen Vogel in an almost wordless performance conveys a wide range of emotion at every turn: the burden of responsibility, fatherly pride, dogged, single-minded vengeance, self-doubt.

There’s technical stuff in both cases worth mentioning: the characters in the 2017 film speak sparse dialogue in a dead language and it all goes by untranslated. Text in the beginning explains this choice, correctly indicating that it’s not at all necessary to understand the story. Each film has gorgeous visuals: ice and snow and winter skies, atmospheric forests. The moments of action in the later film are incredibly well-executed and shaky cam-free, brutal hand-to-hand engagements with crude implements playing out with real flourish and longer range encounters with arrows flying back and forth filled with genuine tension, the results in each instance being genuinely surprising and inventive.

These are both simple stories, emotionally heightened, slow-burning. And while not technically a part of this proposed double feature, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams, his 2010 documentary about the unbelievably beautiful Paleolithic paintings discovered in the Chauvet Cave in France in 1994 that scratches the very same itch. Throw that in between viewings and let yourself soak in the exquisite loneliness.

Comments on this entry are closed.