For 1 Year, 100 Movies, contributor/filmmaker Trey Hock is watching all of AFI’s 100 Years, 100 Movies list (compiled in 2007) in one year. His reactions to each film are recorded here twice a week until the year (and list) is up!

Sometimes as a young filmmaker develops his style and hones his craft, there comes a time when all of the pieces fit perfectly. The script stretches, tight as a drum, with expertly constructed characters and no unnecessary diversions. The actors, from the lead to each supporting role, turn in stellar performances, every gesture or line revealing more about their characters. Finally the direction manages to not only capture the action, but to accentuate it. Everything the director does, from framing to lighting, pushes the film nearer and nearer to perfection, until the viewer wonders, “Could this be this filmmaker’s greatest, most perfect work possible?”

Sometimes as a young filmmaker develops his style and hones his craft, there comes a time when all of the pieces fit perfectly. The script stretches, tight as a drum, with expertly constructed characters and no unnecessary diversions. The actors, from the lead to each supporting role, turn in stellar performances, every gesture or line revealing more about their characters. Finally the direction manages to not only capture the action, but to accentuate it. Everything the director does, from framing to lighting, pushes the film nearer and nearer to perfection, until the viewer wonders, “Could this be this filmmaker’s greatest, most perfect work possible?”

These moments push the popular medium of motion pictures into the realm of art.

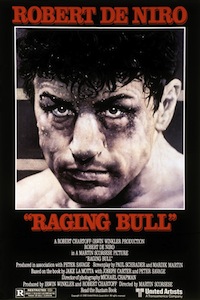

One could look at each of the top four films on AFI’s list and see how this sentiment applies, but for #4 Raging Bull, Martin Scorsese’s most uncompromising film of his career, it has particular resonance.

Four years after Taxi Driver, which, though incredible, often has a distant and sometimes inhuman tone to it, Scorsese is able to craft a film that is just as relentless and visually stunning, but also deeply human.

From its slow motion opening shot of Jake La Motta (Robert De Niro) alone in the ring, we understand exactly what Raging Bull is about. This one man bobs and weaves, fighting not with any physical opponent, but with the shadows that live within his head.

That is not to say that La Motta won’t have to face any actual opponents in the ring, but they are ancillary to La Motta’s struggle against himself. When Jake does fight other boxers, the violence is brutal.

Scorsese is unafraid to show the vicious consequences of life in the ring, and yet bathed in black and white these images have both a richness that makes them deeply emotional and a starkness that makes them palatable.

With all of the undeniable strengths of Raging Bull, it is remarkable to consider that that Scorsese was not this project’s champion from the beginning. That job fell to Robert De Niro.

De Niro read La Motta’s biography earlier and saw something in it that he could grab on to. Maybe it was the deep self-inflicted hurt that La Motta had such skill in dispensing upon himself, perhaps it was the arrogance paired with the insecurity that is such a common and violent mix, or it could have been the passion of an explosive young boxer who, against all odds and in spite of his own corrosive limitations, punched his way to his sport’s biggest stage.

Life is not always punctuated by the concussive blasts of the flash bulbs, as you stand victorious over your fallen foe. Most of our lives take place outside of the ring, in preparation, relaxation, or retreat.

As La Motta scraps his way into recognition through his repeated collisions with Sugar Ray Robinson (Johnny Barnes), his marriage to Irma (Lori Anne Flax) falls into disrepair. This is due in no small part to Jake’s obsession with the 15-year-old Vickie (Cathy Moriarty), a local beauty. Vickie is both naïve and experienced, and fits felicitously with Jake’s view of women.

Jake’s marriage to Irma ends, and in 1947, Jake and Vickie are married.

The entire film is shot in beautiful black and white by Michael Chapman. The only exception is the grainy, textured 8mm home movies of Jake, Vicki, and Jake’s brother, Joey (Joe Pesci).

This visual juxtaposition accentuates what has been documented and what is remembered. The documentation has degraded, but we can see the colors of the clothing, the cars, and the people.

The black and white feels almost dream-like in comparison. It sanitizes certain aspects, but heightens other.

There were practical considerations too. In a historical biopic, getting the color of the gloves or trunks right is not a concern in black and white. Nor is the gruesomeness of the bouts.

The black and white allows Scorsese to be uncompromising with Raging Bull. In Taxi Driver, Scorsese famously color corrected the film so that the blood was more orange than red to avoid an X rating. With Raging Bull, Scorsese has made a choice that serves the story and removes the power that the MPAA censors would otherwise have.

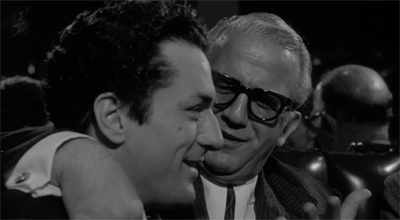

The sport of boxing in the 1940s was, to some extent, controlled by the mob, whose handlers kept the best bouts for complicit boxers. La Motta had gone as far as he could on his own. To get a title shot, he had to make a deal with the local boss, Tommy Como (Nicholas Colasanto).

Jake will get a title shot, but first he has to make good on his deal. First, he has to take a dive.

La Motta is a brute in the ring, and an ill-mannered pig outside of it. The only thing he loves is boxing. The only thing that drives him is the chance at a title, and now he has betrayed his own passions and stained the ugly, yet pure pursuit of boxing greatness.

He has sold himself, and taken a dive for the benefit of an inferior boxer. The grief is too much for someone who knows how to take a punch.

When Jake gets the title, it is no longer on his terms. The passion of pursuit subsides, and with the belt in his hands, Jake begins to lose his focus.

As La Motta’s drive to stay in shape and remain competitive wanes, so too does his libido. This only serves to accentuate his insecurity, and suspicions of Vickie’s infidelity.

A man who only understands achievement through violence, La Motta’s verbal accusations quickly escalate beyond that, and to disturbing levels.

Scorsese uses his camera to add to the aggression. He forces us to move with La Motta as he attacks Vickie. The camera pans in synchronized motion as Jake grabs and hits his wife. The effect is dramatic and upsetting.

De Niro’s intensity makes the moment all the more real.

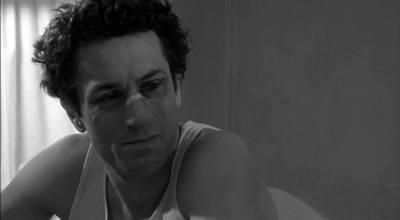

De Niro famously put on weight to play the aging La Motta. 60 pounds over two months is no easy feat, but what I find just as impressive is De Niro’s commitment to his boxing training.

The actor was so focused that he competed in a number of local boxing matches and won a couple of them. La Motta, who helped train De Niro, said that the actor even had the makings of a great boxer.

De Niro definitely looks the part.

When Robinson returns from his military service, he wants a shot at La Motta’s title.

Out of shape and unprepared for Robinson, La Motta cannot hold off his attacks. Scorsese makes the crushing psychological reality of this moment visual through the use of the best zolly shot of all time.

Jake does not go down for Robinson, but is otherwise obliterated. Scorsese just needs one insert to tell us what has become of La Motta’s career.

Rocky showed us what was possible. It made us believe that with hard work and perseverance we could get a shot, and really a shot, regardless of the outcome, was all we needed.

In Raging Bull, four years after Sylvester Stallone’s boxing epic, Scorsese shows us the fractures and pain of our humanity and the results of our slow decay.

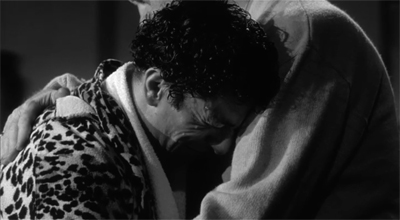

After his boxing days are through, Jake indulges himself. He eats, spends his way through all of his money, and philanders. Eventually Vickie leaves him. At the point that this happens, it is an afterthought. There is no fan fare, no pomp. It’s just a car speeding out of a gravel parking lot, leaving Jake in a cloud of dust.

La Motta’s exploits go too far when he gets involved with an under aged girl at his club. Without the money to post bail, Jake is put in prison.

Here in the darkness of his cell, a man who lived like an animal in and out of the boxing ring, a man who was capable of incredible brutality, stands up and punches the wall until he can no longer take the pain. Jake sits on the cot and has the closest thing to a moment of clarity that he is capable of.

Cast in total darkness, Jake yells “Why are you so stupid?” looking briefly at himself. What he finds must be too devastating, because in the next breath he mutters, “Why do you treat me this way? I’m not an animal.”

Again he forces the blame outside, and away from himself. He simply could not bear it if he allowed for the possibility that everything, all the hurt, all of the loss, all of the bruised relationships, even his current incarceration, was his fault.

Once released, La Motta becomes a mockery of a comedian, working dive bars with other has-beens.

The film ends with a fat Robert De Niro playing a fat Jake La Motta reciting Marlon Brando’s speech from On the Waterfront to himself in a mirror.

The irony and cinematic language does not get any thicker or more delicious than this moment. Terry Malloy in On the Waterfront never got his shot because his brother sold him out, but Jake won it all and lost everything because of himself.

So now this obtuse grotesque individual stands in preparation for one of his shows, and shadow boxes. He once again prepares for a bout, and we are back where it all began. Only this time there is no ring, no flashing lights, and no dreamlike slow motion. Now it is a dingy backroom, stark flat lighting, and the camera won’t even move to reframe when La Motta stands and throws fat wheezing punches at no one.

Raging Bull is one of the most beautiful films about ugly people you’ll ever see. Its stark emotional landscape gives it the air of honesty and the appeal of a cautionary tale.

It is funny to think that this film, when it came out in 1980, barely made its money back and almost ended Scorsese’s career. By the end of the 80s it had won almost universal critical praise, and Scorsese finally had a critical and box-office hit with The Color of Money.

Now Raging Bull tops most critics’ lists of the greatest films of all time, including AFI’s list from 1998 and 2007 and Sight and Sound’s 2012 Directors’ Poll.

A stunning achievement that could only come from a passionate artist with little left to lose, and with collaborators that were hell bent on making something remarkable.

Raging Bull will stand the test of time because it speaks to the worst of what is in all of us, and warns us of what any one of us could become.

Up next, #3 Casablanca (1942)

1 Year, 100 Movies #5 Singin’ in the Rain (1952)

1 Year, 100 Movies #6 Gone with the Wind (1939)

1 Year, 100 Movies #7 Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

1 Year, 100 Movies #8 Schindler’s List (1993)

1 Year, 100 Movies #9 Vertigo (1958)

For links to #10-19, click on 1 Year, 100 Movies #10 The Wizard of Oz (1939)

For links to #20-29, click on 1 Year, 100 Movies #20 It’s a Wonderful Life (1946)

For links to #30-39, click on 1 Year, 100 Movies #30 Apocalypse Now (1979)

For links to #40-49, click on 1 Year, 100 Movies #40 The Sound of Music (1965)

For links to #50-59, click on 1 Year, 100 Movies #50 The Lord of the Rings: Fellowship of the Ring (2001)

For links to #60 – 69, click on 1 Year, 100 Movies #60 Duck Soup (1933)

For links to #70 – 79, click on 1 Year, 100 Movies #70 A Clockwork Orange (1971)

For links to #80 – 89, click on 1 Year, 100 Movies #80 The Apartment (1960)

For links to #90 – 100, click on 1 Year, 100 Movies #90 Swing Time (1936)

{ 6 comments }

Fucking AMAZING analysis, Trey. Well done, sir.

Thanks, Warren. You’re crushing it at Sundance by the way.

Thanks buddy!!

Thank you very much for this amazing review.

I lost all hope that you would ever do the remaining 4 reviews and now it seems like I was wrong. That’s what I call a pleasant surprise.

Keep up the good work.

Greetings from Germany

Thank you, Brendan. I’m glad that you are still reading, and I hope to have the last 3 posted by the end of February if not sooner.

So glad you are finishing up with these Trey! I am still slowly chugging away on the list as well, still in no particular order. The first thing I do every time I finish a film on the list is to check it off my printed sheet and then I immediately go online and read your thoughts for comparison. How excited was I to have finished ‘Raging Bull’ tonight to then find a newly written review. Woot! Your viewpoints are spot on and you chose excellent images for dissection and symbolism. This was a fascinating film to watch and the acting was superb!

Comments on this entry are closed.