For 1 Year, 100 Movies, contributor/filmmaker Trey Hock is watching all of AFI’s 100 Years, 100 Movies list (compiled in 2007) in  one year. His reactions to each film are recorded here twice a week until the year (and list) is up!

one year. His reactions to each film are recorded here twice a week until the year (and list) is up!

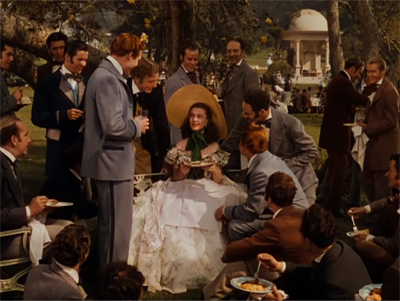

There was something incredible going on in 1939 in Hollywood. Call it naïve arrogance and a belief that popular art was still art. Whatever it was it gave us two incredible films that show the vivid depths of which motion picture was capable. “The Wizard of Oz” came in at #10, and now at #6 we have “Gone with the Wind.”

I find it surprising that Victor Fleming directed both “The Wizard of Oz” and “Gone with the Wind” for most of each film’s principal photography. This gives Fleming the jaw-dropping stat of only director with two films on AFI’s list where both films appear in the top ten.

“Gone with the Wind,” because it is a fable of the American South through the Civil War and into the Reconstruction, and because it was made in 1939, only 75 years from the end of the war, has many of the markers of subjugation and racial intolerance. Yet even in 1939, the filmmakers involved, led by producer David Selznick, knew that they were creating myth and not reality. They were making a watercolor image of the South.

Another surprising aspect of the two 1939 films, which are in the top ten, is that both are built around strong female protagonists. Just as “The Wizard of Oz” is about Dorothy, “Gone with the Wind” is Scarlett’s story. The Civil War and Reconstruction just serve as backdrops for this compelling drama about a woman’s ability to adapt and survive through the radical changes taking place around her.

Many have described Scarlett as the quintessential Southern bitch. British director Victor Seville when talking to Vivien Leigh, who would later land the coveted role, told her, “Vivien, I’ve just read a great story for the movies about the bitchiest of all bitches, and you’re just the person to play the part.” In spite of Seville’s assessment of Scarlett, it is a mistake to overly simplify this character.

Scarlett is tough and always places survival above honor, but many could look at her qualities as markers of strength, will and character. Scarlett as played by Leigh is beautiful, but rarely the helpless object of sexual desire. Even Rhett Butler (Clark Gable) seems to see more a kindred spirit than a sexual conquest. Scarlett is strong, but never masculine. She understands what the culture around her expects from a woman of the time, and bends to that cultural will only so far as she must to achieve her own ends.

As the women take their nap, the men discuss the coming war. Scarlett sneaks away and finds her beloved Ashley to confess her love for him.

Scarlett doesn’t run after Ashley until she hears of his engagement to Melanie. Once the engagement is announced, Scarlett must have him. When Ashley turns Scarlett away, she flippantly marries Charles Hamilton (Rand Brooks) as he and the other men rush off to war.

Scarlett is no vixen, or wilting flower. She moves to Atlanta to live with Melanie. When Charles is killed, Scarlett stays to help the war cause and tend the wounded. When she looks to flee to Tara, the doctor convinces her to stay and care for the pregnant Melanie. Only after the child is born and Atlanta is in flames do Scarlett and Melanie escape with the help of Rhett Butler.

The burning of Atlanta gives us one of the more visually compelling images ever put to film.

To make the burning of Atlanta visually overwhelming it would take a pretty huge undertaking. Selznick’s studio in Culver City had been accumulating sets over its years of filmmaking. Those sets were filled with kerosene soaked garbage and set ablaze behind a flat that was made to look like the Atlanta warehouse district.

When in doubt, set everything in the studio’s back lot on fire.

Scarlett, Melanie, and Prissy (Butterfly McQueen) make it back to Tara, which has suffered neglect and fallen into disrepair. Gripped by hunger Scarlett swears she’ll never be hungry again.

I find Scarlett utterly compelling and sometimes admirable. In this moment, though her motives are often self-serving, she accepts her role as head of the household and resolves to do whatever she has to in order to save Tara and rebuild her world.

Scarlett nurses the ailing Melanie, protects Tara from a Yankee deserter searching for loot, and works the cotton fields alongside her sisters and their family’s servants.

As the war ends, the men who fought return home. It is not long before Ashley returns to Tara in search of Melanie. Scarlett wants to run to him, but the always-aware Mammy (Hattie McDaniel) holds her back.

I would however like to point out that Mammy is the most aware and alert character in the entire film. No one else in “Gone with the Wind” knows as much about the situation at hand as Mammy. She understands that Scarlett wants to run to Ashley, but Mammy holds Scarlett back because to run to Ashley would destroy everything Scarlett has just saved from ruin.

Later Rhett says that Mammy is the only person whose respect he desires, and rightfully so. She is an astute judge of character, she is loyal, and she is just.

As a large black woman in the 30s, 40s, and 50s, Hattie McDaniel was type cast for her entire career as a house servant or maid. It is unfortunate, because she proves that with limited screen time she is capable of creating a complex and insightful character. In spite of the fact that she did it while playing a slave, then servant, McDaniel earns her Academy Award, the first ever awarded to an African American.

With Twelve Oaks destroyed, Ashley stays on to work the fields at Tara. It is not long until he and Scarlett find themselves alone together.

The carpetbagger landlord soon distracts Scarlett from her thoughts of Ashley. He demands his rent, and it is more than Scarlett can come up with in so short a time. She hears that Rhett has been captured and is being held in Atlanta. Scarlett rushes off to seek his aid.

Scarlett turns Frank’s general store into a lumber mill. By employing ruthless business practices, Scarlett quickly regains her fortune and status, but her arrogance leads her into trouble.

Returning home one evening, Scarlett takes her carriage through the nearby shantytown. She is accosted by one of the squatters, but Big Sam, her father’s former field foreman, helps her get away.

In retaliation for the assault, Frank, Ashley and a number of other men decide to go into the shantytown and rout out the people living there. Rhett comes to warn Scarlett, Melanie and the other women that the plot has been found out, and the local Union soldiers are looking for Ashley and Frank.

Without waiting for Scarlett to get into another opportunistic marriage, Rhett marries her. Rhett sees their paring as that of equals, both are ambitious, bordering on unscrupulous. Scarlett never seems to love Rhett and simply sees the marriage as a way to secure her fortune, home in Atlanta and Tara.

Scarlett continues to harbor feelings for Ashley, but does so more to keep Rhett at arms distance and exert her independence. Rhett and Scarlett struggle through the birth and accidental death of their child, Bonnie. It is not until Melanie falls ill and on her deathbed tells Scarlett to take care of Rhett that Scarlett understands what Rhett means to her.

When Scarlett asks him where she should go and what she should do, Rhett delivers his most famous line.

Watching “Gone with the Wind” this time around made me long for the days when a film could be four hours long because the story warranted it. This allows for characters to be well rounded, and thought out. They can make mistakes, then grow from them. They can become tarnished, yet wonderful. They can feel real to us.

An incredible film driven by a single female character, “Gone with the Wind” is a brilliant hybrid of popular and cinematic culture, and though it has fallen two spaces to #6, its place somewhere high on AFI’s list is assured for some time to come.

Up Next #5 “Singin’ in the Rain” (1952)

1 Year, 100 Movies #7 Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

1 Year, 100 Movies #8 Schindler’s List (1993)

1 Year, 100 Movies #9 Vertigo (1958)

For links to #10-19, click on 1 Year, 100 Movies #10 The Wizard of Oz (1939)

For links to #20-29, click on 1 Year, 100 Movies #20 It’s a Wonderful Life (1946)

For links to #30-39, click on 1 Year, 100 Movies #30 Apocalypse Now (1979)

For links to #40-49, click on 1 Year, 100 Movies #40 The Sound of Music (1965)

For links to #50-59, click on 1 Year, 100 Movies #50 The Lord of the Rings: Fellowship of the Ring (2001)

For links to #60 – 69, click on 1 Year, 100 Movies #60 Duck Soup (1933)

For links to #70 – 79, click on 1 Year, 100 Movies #70 A Clockwork Orange (1971)

For links to #80 – 89, click on 1 Year, 100 Movies #80 The Apartment (1960)

For links to #90 – 100, click on 1 Year, 100 Movies #90 Swing Time (1936)

{ 2 comments }

Trey this is a fantastic review; very true and honest about Gone With The Wind.

There were two points that I was waiting for you to mention though. The first being that one night when Rhett carries his vaguely struggling wife up the stairs to rape her, and right before that when he also calls her out on her habit a sipping some brandy before going to bed (earlier too, when he’s courting her and she tries to wash her mouth out with cologne to disguise the scent of brandy).

I know that Scarlett is the pleasure loving sort but it is fascinating to me that she may be an alchoholic, which I think of as a very large weakness.

The morning after his ravaging, she looks at him with almost a fond smile that vanishes the instant he opens his mouth to speak. Which I find to be very strange.

I always felt an affinity with Scarlett because all of her scheming and bitchiness made her seem very human, and made me feel better about all the selfishness I have. She points it out herself, when she and her sisters are picking cotton: “I’m not asking them to do anything more than me.” The problem is her sisters ARE wilting flowers versus her steel magnolia.

Her attraction and devotion to Ashley mystified me, and I’ve had to resign it to a “you always want what you can’t have.” Margaret Mitchell apparently based this affair upon a real story of unrequited love in her family history, but I hope the real Ashley Wilkes wasn’t as mealy-mouthed and waffly as the one on screen.

Strong women are often depicted as mean, undeserving characters, who prey upon weaker men; almost sucking the life force from them. But the actual truth is that quite often they’d prefer someone who matches them in strength

Rosie, I totally agree on your assessment of strong female characters, and even your astute comment about Scarlett’s possible alcoholism. As far as the scene where Rhett forces himself upon Scarlett, I too am bothered by that scene, but did not feel that I could give it the proper amount of time to really explore the meaning and ramifications within the overall story.

I wanted to write about Scarlett first and foremost, and that particular scene felt like a digression, though an admittedly important one. Ultimately I chose the coward’s path and avoided the topic all together. My thought in regards to all of my columns is that if I miss something and it is important to the readers then they’ll bring it up in the comments.

So I thank you for not only being a commenter, but a contributor.

Comments on this entry are closed.