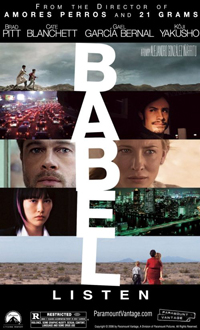

Spanning five languages and three continents, Mexican-born director Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Babel proves film’s unique ability to reach beyond cultural barriers.

Essentially a plea for international tolerance, the movie showcases images that are among the most breathtaking of the year. Iñárritu is at his most poetic when he illustrates humanity stripped of its differences and lets the pictures speak for themselves.

Essentially a plea for international tolerance, the movie showcases images that are among the most breathtaking of the year. Iñárritu is at his most poetic when he illustrates humanity stripped of its differences and lets the pictures speak for themselves.

If the biblical legend of the Tower of Babel is used to explain how humanity became racially divided and why it speaks different languages, then “Babel” is a movie that suggests we are more alike than we think.

After the phenomenal success of last year’s Crash, there will be a temptation by some to label Iñárritu’s film as a natural result of the success of said overbearing Best Picture winner. Both feature multiple character storylines connected by a common thread, but Babel’s treatment is thankfully much more subtle.

A deaf Japanese teenager (Rinko Kikuchi), struggling in the wake of her mother’s suicide, is desperate to connect with her friends. Her father, while vacationing in Morocco, gave a rifle as a gift to a sheepherder whose son accidentally shoots an American tourist (Cate Blanchett) through a tour bus window. Her husband (Brad Pitt) must rely on the kindness of local strangers to get his wife medical attention in the middle of the desert.

Meanwhile, their Mexican nanny (Adriana Barraza) in San Diego has taken their kids to the wedding of her son (Gael García Bernal) in Mexico, and things get hairy when they cross through border patrol.

Meanwhile, their Mexican nanny (Adriana Barraza) in San Diego has taken their kids to the wedding of her son (Gael García Bernal) in Mexico, and things get hairy when they cross through border patrol.

Babel unfolds slowly and mostly in chronological fashion. The stories overlap in time just slightly to add dramatic tension. After the young boys stupidly shoot toward the bus, time shifts backward so we can watch the Americans’ story progress and ultimately collide with the Morrocans.

Waiting for the inevitable moment to arrive is dreadful, and it is that kind of anticipation that fills the entire film. The editing serves to build the movie’s emotion, even as it cuts across countries and languages.

The movie works best when its characters are given a chance to showcase their humanity through some truly expressive cinematography. Iñárritu wields his camera eloquently, using tightly framed close-ups and point-of-view shots to let us inside their heads, especially when there is no dialogue.

The movie works best when its characters are given a chance to showcase their humanity through some truly expressive cinematography. Iñárritu wields his camera eloquently, using tightly framed close-ups and point-of-view shots to let us inside their heads, especially when there is no dialogue.

He also utilizes silence, an underused tactic in modern movies, just as much as subtitles. What results is a seamless brand of storytelling that mimics the movie’s theme of unity.

It is also refreshing to see a movie in which the two Hollywood stars are no more and possibly less important than the unknown actors starring in the other major roles.

Kikuchi and Barraza are particular standouts, lending authenticity and vulnerability to a story that gets temporarily distracted when Pitt is onscreen. Don’t get me wrong, Pitt plays a fully realized character here, it’s just that his very presence throws the film off balance at times.

Kikuchi and Barraza are particular standouts, lending authenticity and vulnerability to a story that gets temporarily distracted when Pitt is onscreen. Don’t get me wrong, Pitt plays a fully realized character here, it’s just that his very presence throws the film off balance at times.

Babel works in a visceral way, as several different dramas unfold at a natural, unhurried pace. No character is on hand to neatly tie up the film’s themes (like how we all Crash into each other), but there is an overall feeling of empathy for everyone that does not come at the expense of a realistic ending. Just because a movie has a downbeat ending doesn’t mean it has to make you feel like crap.

Comments on this entry are closed.