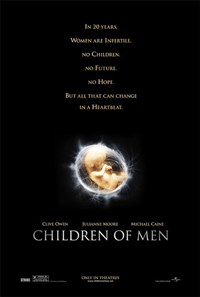

A rare blend of serious science fiction and pulse-pounding action, director Alfonso Cuarón’s Children of Men is the best film of the year. Despite a gloomy apocalyptic setting (that serves as a cautionary warning for us all today), it remains a movie about hope against all odds. The kicker is that this catastrophic future is one that closely resembles an all-too-familiar present.

Men who were once peace activists are now despondent low-level bureaucrats like Theo Faron (Clive Owen). On his way to work in London, a suicide bombing takes place mere yards away. Homeland Security has checkpoints at virtually every curb to keep illegal immigrants out because the last civilized place left on Earth is England, and it is a fascist state.

Men who were once peace activists are now despondent low-level bureaucrats like Theo Faron (Clive Owen). On his way to work in London, a suicide bombing takes place mere yards away. Homeland Security has checkpoints at virtually every curb to keep illegal immigrants out because the last civilized place left on Earth is England, and it is a fascist state.

Islamic fundamentalists forced into internment camps are organizing for a violent uprising. An 18-year old nicknamed Baby Diego –whose idol worship brings to mind shades of Princess Diana—is assassinated after refusing to sign an autograph. His claim to fame? He was the youngest person on the planet.

Children of Men takes place in the year 2027, where women are no longer able to get pregnant and the human race is dying out. This is the future, yes, but there are no spaceships or ray guns. In fact, technology seems to have advanced very little from today. The human race’s sudden infertility is unexplained, and that’s okay. It is merely a device, a metaphor for the loss of hope in the face of destruction. Think of it as a more aggressive extension of today’s global issues. This sense of immediacy is strengthened by two of the most thrilling sequences in recent memory.

Theo’s ex-lover Julian (Julianne Moore) is the leader of a terrorist group called the Fishes. When she and Theo become keepers of a world-changing secret, we are right there with them in a car during a terrifying ambush. What begins as a visceral kick ends tragically, and moves beyond the realm of sheer escapism. The camerawork is more than skilled. Ultimately, it is unsparing, and its first person point-of-view jars us out of complacency. We are no longer simply watching a movie; we are in the middle of a nightmare.

Theo’s ex-lover Julian (Julianne Moore) is the leader of a terrorist group called the Fishes. When she and Theo become keepers of a world-changing secret, we are right there with them in a car during a terrifying ambush. What begins as a visceral kick ends tragically, and moves beyond the realm of sheer escapism. The camerawork is more than skilled. Ultimately, it is unsparing, and its first person point-of-view jars us out of complacency. We are no longer simply watching a movie; we are in the middle of a nightmare.

Bleakness is everywhere in the frighteningly detailed production design. A visit to an empty elementary school includes unused desks and an empty playground, overgrown with weeds and devoid of children’s voices. Refugees are jam-packed into buses, while armed security guards randomly pick out people for execution.

Throughout, Children of Men finds optimistic poignancy in the unlikeliest of places—like a raging battle sequence that takes place right out in the streets. Echoing some of the images we have seen from Iraq, a handheld camera follows Theo in and out of rubble-strewn buildings, dodging no less than three warring factions. The choreography to pull this off is immense, since it was all done in one single take. Unexpectedly, the violence is stopped cold for a brief moment, as all involved see something miraculous. In the midst of chaos, everyone becomes suddenly in touch with their own humanity.

Throughout, Children of Men finds optimistic poignancy in the unlikeliest of places—like a raging battle sequence that takes place right out in the streets. Echoing some of the images we have seen from Iraq, a handheld camera follows Theo in and out of rubble-strewn buildings, dodging no less than three warring factions. The choreography to pull this off is immense, since it was all done in one single take. Unexpectedly, the violence is stopped cold for a brief moment, as all involved see something miraculous. In the midst of chaos, everyone becomes suddenly in touch with their own humanity.

Theo is the perfect modern hero — a cynical, emotionally bruised man who must rise to the task when he is given a huge responsibility out of the blue. Owen carries Theo’s burden with the rugged determination of someone who hasn’t had a reason to live in years. In this smog-filled, blue-hued dystopian world, everyone gets by in their own way.

Michael Caine plays an old hippie who has also given up. He cares for his invalid wife in seclusion, occasionally waxing nostalgic about his radical glory days. Danny Huston is Nigel, Theo’s rich cousin who holes up in London’s famous Battersea Power Station, collecting famous artwork like Michelangelo’s “David.” Cuarón’s distinct vision blends the new classics with the old—floating just outside the power station’s immense windows is Pink Floyd’s famous flying pig from their “Animals” album. Despite blocking out the harsh realities of the outside world, both characters find their own ways to aid Theo in his mission.

Michael Caine plays an old hippie who has also given up. He cares for his invalid wife in seclusion, occasionally waxing nostalgic about his radical glory days. Danny Huston is Nigel, Theo’s rich cousin who holes up in London’s famous Battersea Power Station, collecting famous artwork like Michelangelo’s “David.” Cuarón’s distinct vision blends the new classics with the old—floating just outside the power station’s immense windows is Pink Floyd’s famous flying pig from their “Animals” album. Despite blocking out the harsh realities of the outside world, both characters find their own ways to aid Theo in his mission.

While some may ask why this fate has befallen the world of twenty years yet to come, they would be skirting the questions that Children of Men raises. How we raise our children, or more specifically—how we change our world for those who will inherit it—is a measure of whom we are as a people.

Without shoving any specific political messages down our throats, Cuarón reminds us that in even the bleakest of circumstances there may always be hope.

Comments on this entry are closed.