In 1954, two films starring the phenomenal Toshiro Mifune effectively defined the Western idea of Samurai cinema. One of those films is unarguably one of the most influential films of all time (Seven Samurai), while the other won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film (Samurai I: Musashi Miyamoto), spawned two sequels, and went on to be a cultural powerhouse.

In 1954, two films starring the phenomenal Toshiro Mifune effectively defined the Western idea of Samurai cinema. One of those films is unarguably one of the most influential films of all time (Seven Samurai), while the other won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film (Samurai I: Musashi Miyamoto), spawned two sequels, and went on to be a cultural powerhouse.

Sadly, both of those films would be upstaged for Western audiences by another 1954 film that defined a wholly more visceral genre of Japanese filmmaking: Gojira.

While we’ve all got love for Japan’s most famous rubber-suited radioactive dinosaur, it’s the Samurai trilogy that left an indelible mark upon Japanese culture, tapping into the then very-current desire to return to the samurai culture (much in the way Westerns tapped in to America’s own post-war restlessness). Based off of Eiji Yoshikawa‘s wildly popular (and highly fictionalized) biography of Japan’s most famous swordsman, director Hiroshi Inagaki offered up a historical epic equal parts hero’s journey, love story, and blueprint for manliness that was about as accurate as using Star Wars to explain World War II, which of course caught fire with Japanese audiences.

Criterion has seen fit to honor up the Samurai trilogy with their recently released two Blu-Ray set that restores the series to its vibrant Toho-vision glory, so my question revisiting the trilogy for the first time in 15 years was: How well do these films hold up?

Criterion has seen fit to honor up the Samurai trilogy with their recently released two Blu-Ray set that restores the series to its vibrant Toho-vision glory, so my question revisiting the trilogy for the first time in 15 years was: How well do these films hold up?

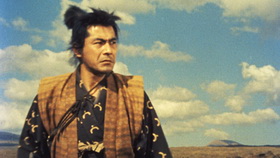

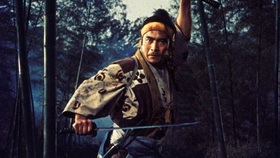

Certainly Toshiro Mifune (already an established star at this point) is at his growly-wise man finest, gifting the young and callous youth Takezo with his trademark seething rage and then showing us his transformation into the calmer, but still restless Musashi until we’re left with a man who has utterly defined his place in the world. He’s impossible to take your eyes off of, and ever bit of the magnetism that prompted Kurasawa to make him a stock player is on display.

However, once you set aside the performance from Mifune (or Koji Tsuruta for that matter, who portrays Musashi’s long-time rival, Sasaki Kojirō), what’s left is a film just steeped in traditional Japanese gender roles and performances that can be almost hilariously off-putting for Western audiences.

However, once you set aside the performance from Mifune (or Koji Tsuruta for that matter, who portrays Musashi’s long-time rival, Sasaki Kojirō), what’s left is a film just steeped in traditional Japanese gender roles and performances that can be almost hilariously off-putting for Western audiences.

As previously mentioned, the film (nor the source novel) could in no way be considered historically accurate beyond getting the names of the players right, and far, far too much time is given over to the various women who fall madly in love with the talented swordsmen who is equally baffled and oblivious to his effect on the fairer sex. Now to be honest: Toshiro Mifune could read the phonebook and I’d probably half fall in love with him myself, but three wholly imagined non-romances across three films just detract from his journey to becoming the man who redefined swordfighting.

Now that’s not to say there’s a lack of real drama or tension in the films: The duel scenes are AMAZING. Tense and suspenseful, and putting Mifune’s tightly coiled power on perfect display with nothing but long, beautifully framed shots of opponents fighting fiercely with stance alone before a single stroke occurs. But unfortunately these moments are few and far between, and the film (rightfully) assumes a level familiarity with the nuances of Shogun-era Japan that might leave some wondering what the hell is going on when it gets to the subtle politics of currying favor from the courtly set.

Now that’s not to say there’s a lack of real drama or tension in the films: The duel scenes are AMAZING. Tense and suspenseful, and putting Mifune’s tightly coiled power on perfect display with nothing but long, beautifully framed shots of opponents fighting fiercely with stance alone before a single stroke occurs. But unfortunately these moments are few and far between, and the film (rightfully) assumes a level familiarity with the nuances of Shogun-era Japan that might leave some wondering what the hell is going on when it gets to the subtle politics of currying favor from the courtly set.

In short these films are vastly important from a cultural impact point-of-view in that they’re effectively Gone With the Wind + Braveheart + Last of the Mohicans times 1000 in terms of their lasting effect on keeping Musashi Miyamoto such a vibrant and relevant figure some 365 years after his death. Those of us who remember the Japan-a-mania of the late 80s/early 90s recall how Musashi’s treatise on swordfighting and philosophy, Go Rin No Sho (Book of Five Rings) was a go to manual for business sharks looking for a little more edge than Sun Tzu’s Art of War. But that impact translates poorly to American sensibilities as the formal style of presentation can read almost too comical for its own good without some background on mainstream Japanese cinema in the 50s.

All in all, I was glad to revisit the trilogy I was so deeply enamored with in younger days (especially restored to such colorful luster and vibrancy), but those looking for Kurasawa-esque adventure and drama may well find themselves disappointed.

Comments on this entry are closed.