The Japanese master filmmaker Yasujiro Ozu (Tokyo Story, Late Spring) is not known in the Western world for his comedies, even though he came into the Japanese film business writing gags in a pinch for early comedy shorts.

No, he is famous as the top purveyor of the Japanese family drama, and his films are prone to quiet moments of devastation and poignancy. Decidedly anti-melodramatic, his formal rigor (developed over a lifetime working in the Japanese film industry) puts his audience on the same level as his characters, delivering instant empathy. His stories often seem like deceptively simple slice-of-life narratives, but the deeper truths they reveal come directly from the strict filmmaking strategies that he perfected over time.

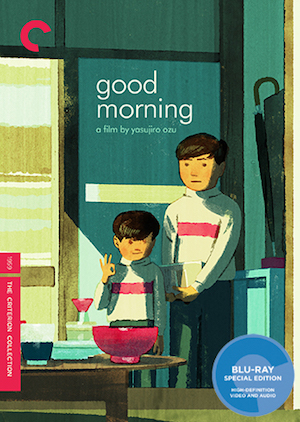

1959’s minor-key comedy Good Morning, or Ohayo, is a late-career color movie, one of only six the director would ever make. The Criterion Collection has just released a stunning new 4K restoration on Blu-ray that will no doubt resuscitate its name, along with Ozu’s reputation, for being just as skilled with a fart joke (or 100) as he his with unspoken feelings and pained loyalties.

Good Morning takes place in a Japanese suburban neighborhood, but unlike most of his films, everyone lives very close to each other. This makes it easier for a comedy of misunderstandings, as they pile up a lot quicker when people are in and out of each others’ houses all day. It’s almost as if the people who live on this block are actually members of the same family. This is put to fine staging use through a recurring shot of the busy walkway between houses — and it’s reminiscent of silent comedies.

In fact, Good Morning has been labeled as reimagining of Ozu’s own 1932 silent classic I Was Born, But…, which is included in its entirety on this wonderful Blu-ray as an extra feature. This black-and-white treasure has the subtitle “A Picture Book for Grown-Ups,” and follows two mischievous kids growing up in the suburbs who slowly realize their Dad isn’t invincible. Ozu hasn’t he doesn’t have all the signatures of his style set in stone yet, or his expertise with extended-family plots yet. He has all that in place by the time he makes Good Morning, however, so the two films are more spiritual cousins than Good Morning is a straight-up remake.

Good Morning also follows two young brothers, but the film’s central complication isn’t the slow realization of the complications of adulthood. In that vein, I suppose, Good Morning mocks Japanese fussiness, though — specifically, the culture’s embrace of meaningless small talk. The kids are accused of talking too much by their father and they fight back, saying all adults do is talk, talk, talk, about nothing that matters. Making fun of it, the boys and their friends go on a “silent strike,” and they develop their own form of communication that doesn’t rely on language at all, but rather, farts.

Yes you read that right, this is known as Ozu’s “fart movie.”

(It’s hilarious in one of the Blu-ray’s extra featurettes to see legendary film academic David Bordwell explain the subtleties of the characters’ farts: “The farts in the movie are not, I would say, completely real farts. They’re tuned farts. They’re kind of toned farts. They have different registers.”)

Just as the slightest deviation in the sounds of different characters’ farts is funny, so are the slight differences in behavior of all the people crammed together in this small space. This kind of atmosphere, of course, forces one to be polite. The families rely on daily pleasantries to make like bearable, but ironically, a certain amount of gossip is also okay, as long as it’s not in the form of grand accusations.

I mentioned earlier Ozu’s signature way of developing empathy for his characters. Part of it comes from his consistent camera placement. It’s always low to the floor, never looking down on them. His characters look almost directly into the camera, (I have to believe that Errol Morris is an Ozu fan.) and especially in Good Morning, the conversation spaces are matched almost perfectly when he cuts back and forth using the reverse angle.

Especially since Good Morning was shot in Technicolor and so much of it takes place in meticulously designed, often time symmetrical interiors, it will be impossible for any modern filmgoer not to be reminded of Wes Anderson. Ozu’s set design is impeccably well-lit throughout the frame. There are clean lines throughout, with strategic swaths of matching color that draw your eye. in short, pause this movie on any random shot and you’ll find something would make any decent photographer supremely jealous.

I had seen I Was Born, But… once before and was thrilled to find out it would be released on this Blu-ray, thinking it was reason alone to get a copy of it. But Good Morning is such a fantastic surprise, and worthy of discussion among any of Ozu’s better known dramatic works. In addition to the silent feature and the Bordwell featurette, there’s an enlightening video essay from critic David Cairns, and the 14 surviving minutes of Ozu’s 1929 silent film A Straightforward Boy.

Comments on this entry are closed.