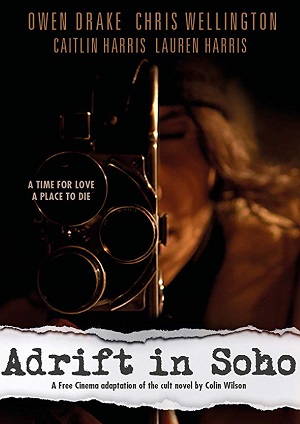

[Rating: Rock Fist Way Down]

A jumbled, chaotic mess of imagery, character sketches, bad jazz, and even worse storytelling, Adrift in Soho is just that: adrift. Abandoning any pretense of approachable character arcs, narrative momentum, or even an established sense of time and place, the film by director Pablo Behrens surrenders itself to the bohemian soul of the 1961 novel on which it is based and finds itself utterly lost in the ethereal vibe serving as the film’s backbone. The finished product is a confusing and unfocused pastiche of scenes that rarely cut together with any cohesion, which are themselves hampered by acting performances that are middling at best, and cringe-worthy at worst.

So, what is this film about? Well, that is hard to say, and is something Adrift in Soho makes its audience work hard to discover. The opening scenes do not establish a time or place for the events portrayed, with characters engaged in random conversation talking about “Soho-itis” without any further explanation. Repeated mention of Soho-itis in these chats between characters not set up or introduced in any way draw out the fact that the picture is indeed set in London’s west end, though it isn’t until a lunch conversation over an hour into the movie that the date of 1955 is established.

Behrens doesn’t seem to think it’s important that the audience know when or where the film is set, which would seem like an odd choice on the face of things if he didn’t also abandon any attempt to introduce his characters before throwing them at the audience mid-conversation. Sure, this technique can work for a time (think of Vincent and Jules’ introduction in Pulp Fiction), but Behrens doesn’t do this to create layered characters via conversational juxtaposition (i.e., setting the mundane chit-chat of burgers in France against contract murder). In Adrift in Soho, it seems to be an attempt to translate the breezy, unmoored lifestyle of English beatniks into a cinematic aesthetic.

It simply doesn’t work, though. By the time the audience learns enough about the characters to understand their position in the story and the journey they are on, the film is nearly over and any opportunity to relate or learn from these people has vanished. There’s the aspiring writer, Harry (Owen Drake), his actor/grifter friend James (Chris Wellington), the “free filmmakers” Myra (Lauren Harris) and Marcus (Angus Howard), and American student Doreen (Caitlin Harris), all of whom just sort of drift in and out of the narrative with little purpose for the majority of the film. And as bad as all that is, none of them do particularly good work in their scenes, which seems to be the result of not just limited acting ability, but wholly atrocious dialogue put on the page for them.

As the scenes tilt between pub conversations, marijuana parties, commercial shoots, and other seemingly random slices of life from the period, some semblance of a story begins to take shape for the characters. There’s Myra and Marcus’ struggle to maintain artistic purpose in the face of commercialism (with a dash of communist struggle thrown in), James’ never-ending quest to survive and thrive without a job, and Harry’s transition into adulthood between the opposing forces of art and proper society. If assembled well, these characters and their various journeys could have woven together into something with a lot to say not just about mid-20th century London society, but the unmoored and lost experience of any 20-something struggling to give their life purpose and direction.

Again, though, by the time any of this begins to take shape as a recognizable arc for any of the characters (if indeed it ever does for some of them), the audience has no investment in what’s going on with these people. It would be like if Pulp Fiction was just about Vincent and Jules, and the film ended with them leaving the apartment with Marvin (alive). Some atmosphere has been established, and there’s a rough understanding of who these people are, yet to what end? The languid, lazy jazz scored throughout the picture doesn’t provide any answers, though it does tease at the possibility that a 1940s private detective might start monologuing over it at any time.

What is Behrens trying to say with Adrift in Soho? Sadly, this reviewer was unable to parse that out. In trying to capture the Kerouac-esque spirit of carpe diem escape from societal expectations, the movie has abandoned any pretense at character establishment or narrative cohesion. This feels like a film unbound by the restraints of convention, which may well by in line with the novel on which it was based, yet translates poorly to the screen. The actors don’t seem capable of bridging the gap between the ethereal and the tangible, and fail to connect the audience on an emotional level to that which the script and movie writ large can’t manage. About the only thing this one does right is connect to the title of its source, for this picture is truly, unquestionably adrift.

Comments on this entry are closed.