Director Joe Wright finally makes the film he should have been making all along. Anna Karenina is his best film yet, and may end up being his magnum opus.

Director Joe Wright finally makes the film he should have been making all along. Anna Karenina is his best film yet, and may end up being his magnum opus.

Wright has always had a tendency towards melodrama. His films Pride and Prejudice and Atonement both show this, but the Soloist shouts it from the mountaintops.

With his 2011 film Hanna his propensity for melodrama becomes rooted in his visual metaphors. Hanna is a thriller children’s story in the vein of the Brothers Grimm, full of manipulative parents, evil witches, and gingerbread houses.

Though I appreciate portions of Hanna, the first half of the film is excellent, its odd pacing and unbalanced use of his visual metaphor gave me the feeling that Wright was dabbling. All of the Grimm-ish flourishes were awkwardly motivated. So instead of just having blood all over the teeth of the antagonist to promote a wolfish grin, Wright makes her obsessed with dental hygiene.

Though I appreciate portions of Hanna, the first half of the film is excellent, its odd pacing and unbalanced use of his visual metaphor gave me the feeling that Wright was dabbling. All of the Grimm-ish flourishes were awkwardly motivated. So instead of just having blood all over the teeth of the antagonist to promote a wolfish grin, Wright makes her obsessed with dental hygiene.

In Anna Karenina, Wright throws caution to the wind.

Wright’s latest film is reminiscent of Peter Greenaway’s best. The Cook the Thief His Wife & Her Lover and Prospero’s Books had incredible talent in each cast, but Greenaway relied almost entirely on the sets and framing compositions to tell his stories.

Wright’s latest film is reminiscent of Peter Greenaway’s best. The Cook the Thief His Wife & Her Lover and Prospero’s Books had incredible talent in each cast, but Greenaway relied almost entirely on the sets and framing compositions to tell his stories.

Wright relies on the elaborate sets and remarkable visual transitions to spin his tale. Set largely on a theatrical stage, Wright unapologetically creates a consuming visual metaphor, and makes no excuses for a film that the viewers must acknowledge as a construction.

Anna Karenina takes place at the end of the Russian aristocracy in the late 19th century. The pretense and façade inherent in the sociopolitical arena of Russia at that moment was itself theater. It feels as though Wright has simply put the story where it belongs.

Anna Karenina takes place at the end of the Russian aristocracy in the late 19th century. The pretense and façade inherent in the sociopolitical arena of Russia at that moment was itself theater. It feels as though Wright has simply put the story where it belongs.

Wright uses the nooks and crannies of live theater to tell us about Leo Tolstoy’s characters. In one scene Konstantin Levin (Domhnall Gleeson), leaves the royal court of Moscow and goes to visit his brother, Nikolai (David Wilmot). Konstantin climbs the steps of the backstage up into the riggings of the theater. Here throngs of impoverished Muscovites operate the curtains and backdrops, which make possible the pageant of the wealthy aristocrats below. This is where Nikolai lives, backstage, a place that is necessary, but meant to be ignored and unseen.

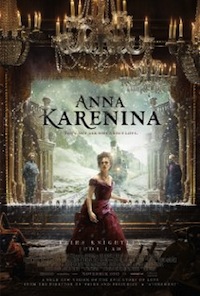

The performances in Anna Karenina are not always booming theatrical portrayals, but when they are it fits seamlessly with the surroundings. Keira Knightley, who is known for her ability to chew the scenery, is well cast and gives substance to the melodrama. This is her world. Matthew Macfadyen, as Anna’s brother Stepan Oblonsky, keeps pace with Knightley’s theatricality.

The performances in Anna Karenina are not always booming theatrical portrayals, but when they are it fits seamlessly with the surroundings. Keira Knightley, who is known for her ability to chew the scenery, is well cast and gives substance to the melodrama. This is her world. Matthew Macfadyen, as Anna’s brother Stepan Oblonsky, keeps pace with Knightley’s theatricality.

And lest I forget, there is Tom Stoppard.

And lest I forget, there is Tom Stoppard.

Stoppard has been responsible for writing the screenplay for a number of directors’ best outings. Stoppard wrote Empire of the Sun, which I often argue is Steven Spielberg’s best film, and was a project that David Lean himself abandoned. Stoppard penned Brazil, which is still endlessly watchable and defensible as Terry Gilliam’s best work. He co-wrote Shakespeare in Love, which won him his Oscar, stole some of Spielberg’s thunder, and is probably John Madden’s most notable film. Now Stoppard does the same thing for Wright’s Anna Karenina.

With the huge cast, the pageantry, camera movement, and overt visual transitions we could get confused by the swirling colors and lost in the sea of characters from Tolstoy’s classic novel. Wright and Stoppard each do their part to keep us grounded, while dazzling us with the elegance of craft that each artist brings to this collaboration.

{ 2 comments }

I always forget to keep up with what Tom Stoppard is doing in the film space, his films almost always seem to turn out well, and I love The Coast of Utopia

I finally saw this film and I adored it! Sad it was snubbed by the Oscars because I thought as well that both Wright’s and Stoppard’s work on this film brilliant.

Long have I loved this novel and I am thrilled with this new version of its telling.

Comments on this entry are closed.