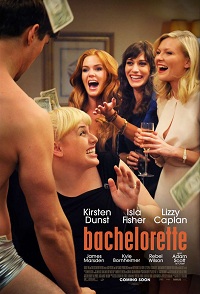

Bachelorette is available on VOD now and arrives in theaters on September 7. Editor-in-Chief Eric Melin has a way shorter video review of Bachelorette here.

In her interview with Marc Maron on his WTF podcast, Amy Poehler notes that the fundamental difference between being a man in comedy and being a woman in comedy is that the women tend to be compared to one another a whole lot more. This is indicative of issues existing in a larger context, to be sure—the same environment that fed fuel to the fire that was the backlash against Lena Dunham’s Girls—but Poehler’s point carries just as much weight in this spectrum.

In her interview with Marc Maron on his WTF podcast, Amy Poehler notes that the fundamental difference between being a man in comedy and being a woman in comedy is that the women tend to be compared to one another a whole lot more. This is indicative of issues existing in a larger context, to be sure—the same environment that fed fuel to the fire that was the backlash against Lena Dunham’s Girls—but Poehler’s point carries just as much weight in this spectrum.

It’s true: There is the tendency when discussing comedic women—be they stand-ups or comic actresses—to draw comparisons, to spiderweb, to mention what predecessor this performer “owes a great deal to.” And while I don’t think there is any inherent ill will in this type of criticism, it does seem to imply, even subtextually, that there isn’t originality or innovativeness or true creativity at work in any given text.

For this reason, and many others, I had every intention of writing about Bachelorette without once mentioning Bridesmaids. They’re completely different films—in style, in tone, and in mission statement—and it is with anticipatory frustration that I expect many a lazy journalist or blogger will link the two films in their reviews of Bachelorette, because, on the face of it, Bridesmaids is perhaps the most available and current cultural text by which to compare. I did not want to be one of those critics.

However, with the intended purpose of using the juxtaposition of the two films in order to illustrate a larger point, allow me to be that kind of critic, just this once.

However, with the intended purpose of using the juxtaposition of the two films in order to illustrate a larger point, allow me to be that kind of critic, just this once.

Bachelorette is deceptive, and was promoted ever-unfortunately with a trailer that completely belies what the film actually has to offer. Even the title sequence—distorted power-punk playing in the background, vintage yearbook photos with captions in pink marker—feels familiar, uninviting, and unworthy of opening the film. But from there on in, Bachelorette is a gem, and one of the most pleasurable cinematic experiences I’ve had this year. Here’s an attempt at trying to unpack why that is.

There’s a great line that Jenna (Lizzy Kaplan) says about 10 minutes into the film, her eyes scanning the crowd at the rehearsal dinner for Becky (Rebel Wilson) and her fiancee. She chews a straw in between her teeth, her body jittery with cocaine, and she says: “It’s like a Jane Austen novel on crack.” Having watched the film three times now, this line sticks out the most. It isn’t the funniest by a mile, but it seems to encapsulate rather nicely and concisely what’s happening in Bachelorette. The movie itself is kind of like a Jane Austen novel on crack, or, because it’s taking place in upper-class Manhattan, an Ann Beattie story on coke. [Sidenote: There hasn’t been this much coke use in a movie I love since Uma Thurman overdosed in Pulp Fiction.]

The reason I so enjoy Jenna’s distilling line is that I think it also embodies what I find so rewarding about Bachelorette, which is an emotional authenticity and complexity in character that was absent from Bridesmaids. To be sure, I thoroughly enjoy that film as well, and would agree that it deserves all of the praise it has received. It’s a strong script, a strong cast, and it’s funny as hell. But I don’t find Bridesmaids to be a challenging film. It is not a film that takes risks. If Bridesmaids proved that women can shit in the street, Bachelorette proves they can be disgusting in an entirely different way. Even when it slightly misses the mark, the film presents a set of characters with fully developed interior landscapes, and that is something more audacious and powerful than sink-shitting.

The reason I so enjoy Jenna’s distilling line is that I think it also embodies what I find so rewarding about Bachelorette, which is an emotional authenticity and complexity in character that was absent from Bridesmaids. To be sure, I thoroughly enjoy that film as well, and would agree that it deserves all of the praise it has received. It’s a strong script, a strong cast, and it’s funny as hell. But I don’t find Bridesmaids to be a challenging film. It is not a film that takes risks. If Bridesmaids proved that women can shit in the street, Bachelorette proves they can be disgusting in an entirely different way. Even when it slightly misses the mark, the film presents a set of characters with fully developed interior landscapes, and that is something more audacious and powerful than sink-shitting.

The best performance in the film comes from Kirsten Dunst, who uses the leftover existential dread from her brilliant role in Melancholia to her advantage here in her portrayal of Regan, the closest thing the film has to a protagonist. She’s the anti-hero to end all anti-heroes, and were Bachelorette a different film—distributed by a bigger studio after several focus group tests—it’s inevitable that we would have been given at least one reason to like Regan. But, mercifully, we don’t. She’s miserable, beginning to end. Writer/director Leslye Headland’s screenplay allows us instead to understand Regan rather than give her some meaningless idiosyncrasy that endears an audience to her, and that’s an important decision that catapults this film into higher quality. Regan is terribly unlikable, and yet, at least for me, depicted with an incredible amount of authenticity and humanity so as to be wholly identifiable.

She’s prone to repeating the same anecdote to anyone who will listen, one that details rather cavalierly her experience reading to pre-teen chemo patients. [“I gotta go read some books to these cancer kids,” is how she puts it.] She gets the attention of her Asian assistant by saying, “Hey, Chinatown.” Even the groom’s party agrees that, “There are serial killers and then there’s Hannibal Lecter. There are girls and then there’s Regan.”

However, somewhere near the midpoint of the film, the audience is delivered unto understanding through a terrific monologue, one that Dunst lends nuance and complexity. “You know what I keep thinking?” she says. “I did everything right. I went to college. I exercise. I eat like a normal person. I got a boyfriend in med school. And nothing is happening to me.” Jenna asks, “Are you all right?” and Regan replies, “No, I just told you, I’m fucking miserable.”

However, somewhere near the midpoint of the film, the audience is delivered unto understanding through a terrific monologue, one that Dunst lends nuance and complexity. “You know what I keep thinking?” she says. “I did everything right. I went to college. I exercise. I eat like a normal person. I got a boyfriend in med school. And nothing is happening to me.” Jenna asks, “Are you all right?” and Regan replies, “No, I just told you, I’m fucking miserable.”

Being that this is a film about brides and bridesmaids, the conditions are so much in place for the emotional makeup of our protagonist [usually our maid of honor] to be one built on jealousy. It’s in the cards, and it’s easily understandable. But what Regan has going on is far more involved, rooted, if I may wax psychological, in a deep-seated unhappiness that extends far beyond the implications of not being the first of her friends to get married. And it’s written all over her dialogue in the film; all over Dunst’s face. When her plan to replace Becky’s torn dress—the plot device that is the least important thing in the film, but does serve as a throughline—turns sour upon realizing the only dress available the night before the wedding is the one that Regan herself has always dreamed of getting married in, though in a smaller size, we come to realize that it isn’t about the dress at all. It isn’t about the wedding. It’s about living a life wherein “nothing is happening to me,” a terrific phrase that suggests unbearable stagnancy. Trevor (James Marsden) puts it best when he says, “I think you’re unhappy and you have no reason to be, and that’s why you hate yourself.”

The way the film handles tougher, grittier material like this—see also: bulimia, suicide, drug abuse, privilege—is sure to be seen by some as uninformed and exploitative, or else gimmicky and half-baked. However, the triumph of Bachelorette is in its ability to normalize behavior and situations that don’t usually find their way into films of this nature without using them as teachable moments. There’s no shooting-star, the-more-you-know lesson to be learned.

Leslye Headland—in her directorial debut it’s worth nothing—only sets out to prove the truth of a human situation, to find where the deeper stories are in a well-trodden story we’ve seen before, and the end result sets the bar incredibly high for whatever she does next.

{ 1 comment }

In your last paragraph you write, “Leslye Headland—in her directorial debut it’s worth nothing—” Did you mean to say it’s worth nothing ? Or perhaps, “it’s worth noting–” ? Big difference.

-bill

Comments on this entry are closed.