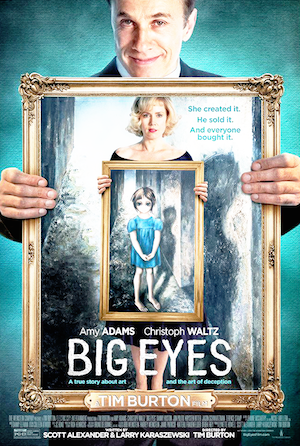

How could Tim Burton possibly lose with a story like Big Eyes?

Margaret Keane (Amy Adams) is as complex a character as one could want. Meek enough to suffer through two marriages with restrictive and manipulative men, somehow Margaret Keane found the inner strength to leave both men in an era that did not look favorably on women who did such things.

If only as an exploration of gender roles in the 1950s and 1960s, Burton already has a wealth of material in Margaret Keane’s story, but there is so much more.

In the 1950s Margaret leaves her first husband to strike out on her own as a single mother. She is a passionate painter and devoutly religious, but her works are seen as a mix of strange and sincere. She falls in with a charismatic salesman, Walter (Christoph Waltz), who sees the emotional appeal of Margaret’s work.

Walter also has the showmanship to sell the paintings to the public. He provides the story behind these flat, sad big-eyed waifs, and in so doing takes the credit for them. Since the world now thinks that Walter is responsible for Margaret’s paintings, she is forced to work in seclusion, keeping their secret until she once again finds the strength to leave her husband and ultimately battle him in court.

You can see how one need just get out of the way of such a story, but Burton and screenwriters Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski rush the plot and only give a cursory nod to the crushing psychology of Margaret Keane’s unique situation.

You can see how one need just get out of the way of such a story, but Burton and screenwriters Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski rush the plot and only give a cursory nod to the crushing psychology of Margaret Keane’s unique situation.

They suffer from what I like to call bad history teacher syndrome. Burton et al are too interested in the what and not enough in the how or the why.

Why does a woman whose paintings are hugely popular, but contentious and hated within the fine arts community, allow someone else to take credit for her work for a decade? Where would Margaret Keane be without her manipulative, controlling, carnival-barker husband Walter?

These questions point to the struggles embedded in Margaret Keane’s situation, but the film avoids asking them or answers them all too quickly. When we see Walter as a bigger liar than we thought, a point that is anticlimactic to say the least, and a drunk, then Margaret leaves for Hawaii with little consequence. She becomes a Jehovah’s Witness and decides that she can no longer live a lie.

These questions point to the struggles embedded in Margaret Keane’s situation, but the film avoids asking them or answers them all too quickly. When we see Walter as a bigger liar than we thought, a point that is anticlimactic to say the least, and a drunk, then Margaret leaves for Hawaii with little consequence. She becomes a Jehovah’s Witness and decides that she can no longer live a lie.

These simple answers for hugely complex issues just don’t satisfy.

Maybe the script and film suffer from the fact that Margaret Keane is still alive. Had the film been made after her death, the writer and filmmaker would be forced to speculate about her motivation and emotional struggles.

This speculation is what Big Eyes sorely needs.

Comments on this entry are closed.