[Rating: Rock Fist Way Up]

Re-imagining a story that’s stitched into the hearts and minds of fans by way of not just the source material but also by other film adaptions is no easy task, yet director Greta Gerwig isn’t in the “easy” business. No, Ms. Gerwig has achieved both commercial and critical success as a female director in Hollywood, so it stands to reason that her next near-impossible task would be to take a swing at adapting one of the most cherished literary works in the American canon. True to form, she has absolutely knocked it out of the park with her take on Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, which is as affecting as it is relevant.

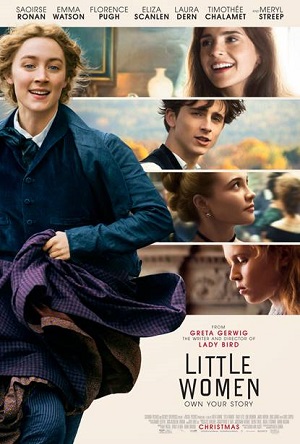

For those that haven’t read the book or seen the roughly half-dozen film adaptations to date, Little Women spans about five years in the lives of the March sisters in 1860s Massachusetts. These four siblings live with their mother (Laura Dern) in a modest cottage across the way from the wealthy Mr. Laurence (Chris Cooper), whose grandson Laurie (Timothée Chalamet) is more or less a 19th century manic pixie dream boy. The four sisters from oldest to youngest are Meg (Emma Watson), Jo (Saoirse Ronan), Beth (Eliza Scanlen), and Amy (Florence Pugh), who all love each other dearly, yet struggle to varying degrees to find their own unique place in the world.

Gerwig’s take on the novel abandons the traditional linear narrative structure and starts near the end of the story, when all four sisters have separated into their own adventures and are reflecting on a shared life of happiness and heartbreak. One of Alcott’s greatest accomplishments with the original text was crafting genuine, lived-in characters for all four sisters, imbuing them with realistic and relatable dreams specific to each. Gerwig’s adaptation is no less thoughtful in its presentation of the March girls, from the independent-minded Jo, to the shy Beth, the repressed but pious Meg, and the jealous but oft-overlooked Amy. And yet there are a multitude of shades to each young woman, so none of the ladies is wholly defined by any singular attribute or event.

When the book was first published in 1868, it served as a unique coming-of-age tale to a demographic that rarely saw any nuance in their presentation in popular entertainment. Reflecting very real attitudes of women not just of that era but throughout history, the novel acknowledges a wide array of personalities that transcend the faithful homemaker model. Indeed, Little Women has given voice to generations of young ladies that found/find some measure of representation in a story about women written by a woman.

Gerwig’s debut feature, Lady Bird, received a great deal of well-deserved praise for its presentation of teenage angst in the 21st century, so her move into Alcott’s world is something of a lateral one. Much like if John Hughes had pointed his lens at Huckleberry Finn or even The Catcher in the Rye, there’s a connective tissue across generations that speaks to the universal plight of passing from childhood to adulthood, and some writers/directors just get it. Gerwig certainly does, anyway, as evidenced by her willingness to slow down and allow her characters to be human beings that alternate between silly (as when Jo and Laurie dance outside of a party) or serious (Amy’s confrontation with Laurie near the end). Yet these aren’t framing moments for the narrative, or even the characters, but rather fleeting memories whose existence coalesce over time to tell the audience more about these people than any monologue or narration ever could.

Little Women as directed by Gerwig is also a strikingly beautiful film with visuals that compliment the patience of the script. Just as the story pauses to revel in the life-altering minutiae of a single dance or conversation, so too does the film stop to drink in the beauty of a cloudy day at the beach or a sunny walk on a ridge above town. Gerwig also makes wonderful use of lighting to denote the frequent jumps between time periods while simultaneously evoking distinct emotions for the different eras portrayed, desaturating scenes that reflect a loss of warmth or innocence. They represent small details yet demonstrate the thoughtful nature of every aspect of this production, from the script right down to the costume and set designs (which are exquisite).

It’s difficult to single out any of the performances, as all ring true with a trusted aura of personal conviction that speaks to each actor’s jealous guardianship of their role. And while Ronan has perhaps the most to do by way of the structure of the narrative, it is Pugh who stands out amongst the leads as Amy, who must layer her performance with equal parts impetuousness and sincerity. On the supporting side, Chalamet seems to be having a blast as Laurie, who manages to be everything to everyone in the story, yet it is Meryl Streep as Aunt Josephine, the miserly widow with a heart of gold, who really shines when coming off the bench in this one.

Perhaps most impressive of all is how the film manages to feel as relevant and identifiable 150 years after the period in which it is set. So much is made about the evolving nature of adolescence in the era of millennials that it seems ludicrous that a story about four young 19th century women could resonate as clearly as 2019’s Little Women does. Gerwig and her actors give voice to universal experiences like sibling rivalry and gender non-conformity that allows it to bridge the gap between the epochs, and while Ms. Alcott certainly deserves a share of that credit, Gerwig’s take on the material breathes new life into it. Superbly acted, thoughtfully assembled, and beautifully presented, this iteration of Little Women has all the ingredients necessary to stand the test of time, where audiences prefer, “imaginary heroes to real ones, because when tired of them, the former could be shut up in the kitchen till called for, and the latter were less manageable.”

Comments on this entry are closed.