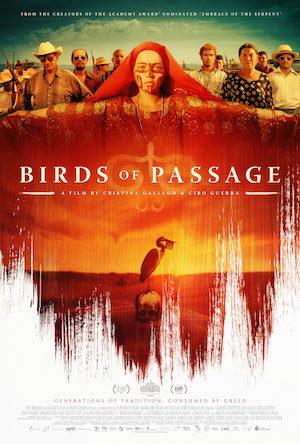

[Rating: Solid Rock Fist Up]

A sober exploration of family, tradition, honor, greed, and colonialism, Birds of Passage (showing now at the Tivoli) slices through expectations to present a film that is laser-focused on a specific time, people, and place. Tracking the birth of the modern drug trade in Columbia during the second half of the twentieth century, Birds of Passage spreads its wings to cover the intersection of modernity and indigenous Columbian culture with devastating honesty. And while it is a sometimes challenging watch, the film is an essential primer for any examination of modern Pan-American sociopolitics.

Starting in the early 1960s, Birds of Passage opens with a traditional indigenous courting ceremony for young Zaida (Natalia Reyes), who is a member of northern Columbia’s Wayúu tribe. The Wayúu may be living in the 1960s, but their customs and traditions date back centuries, and little has changed for them in that time. For example, when a young man named Rapayet (José Acosta) proposes to Zaida, visions and omens inform much of her family’s decision whether or not to accept, along with considerations that weigh the transgressions of the man’s ancestors.

Rapayet is an interesting guy, though. Unwavering in his loyalty to Wayúu customs, yet just as determined to earn the money needed to pay for Zaida’s dowry, Rapayet wants to have his cake and eat it, too. When he learns that there’s money to be made selling marijuana to “gringos” from the north, he partners with a friend to begin moving product. For a time, he’s able to balance the practicalities of both the new and old worlds, yet as the strains of family versus business loyalties wear on him, it becomes clear that this precarious arrangement will not last.

Directors Cristina Gallego and Ciro Guerra wisely keep the film moving by breaking Birds of Passage into chapters that jump a handful years between each section. Each chunk of the picture presents one integral piece of the story, establishing a narrative connection to the next with the time between serving like an incubator for the decisions made. What starts out early on with a couple dozen pounds of weed on mules develops into a sophisticated operation with private runways and planes. Where a knife or machete was carried early on, a pistol, and then a machine gun, follows. It’s not just the drug operation, either: entire communities transform, as do the people, their attitudes, and even their children (and none for the better).

Birds of Passage isn’t just talking about the literal realities of the drug trade in Columbia with all of this, but the process of colonialization and the encroachment of the “new world” on any indigenous people. Rapayet is a smart guy and knows that in order to get what he wants (Zaida), he’ll have to dip his toe into a world that is fundamentally at odds with his people. Like any reasonable person, he tries to uphold the ideals of his community while mingling with those that don’t understand the nuances of a unique and proud people. Whether it is Columbus, Cortez, or the pilgrims, the story is always the same: the outsiders want more than can be offered, and the stain of that interaction will reverberate through untold generations like poison seeping into a water table.

As the film moves through its different sections, spanning the 60s and 70s during the early boom of Columbia’s drug economy, Rapayet remains the ostensible focus of the script, which is one of the few stumbling points of Birds of Passage. Acosta plays the character with a stoic and impenetrable fortitude that doesn’t reveal much, and while it seems to be a deliberate choice, this bottled-up disposition makes him tough to identify/sympathize with. Zaida drifts in and out of the story as well, and is indeed important to its resolution, yet she too is somewhat under baked as a character and exists as more of an idea than a real person.

Rapayet’s friend and business partner, Moisés (Jhon Narvaez), is a departure in this regard, as is Leonidas (Greider Meza), a young man who comes of age during this turbulent period. Their outsized personalities and obvious disregard for local customs set them apart and represent the region’s future, when the modern world will eventually obliterate what little remains of northern Columbia’s old ways. This juxtaposition of personalities seems altogether appropriate, then, and while not always cinematic, it is at least true to the land and her people. Much like the color-drained landscape that surrounds the Wayúu, which Gallego and Guerra come back to again and again, there is beauty in desolation, made all the more striking when viewed next to something lusher (and dangerous).

At a breezy 125 minutes, Birds of Passage doesn’t feel like a film that crosses the two-hour mark, moving with a gradual inevitability that builds like a tsunami with each passing chapter. This tidal wave analogy is particularly apt when considering the score by Leonardo Heiblum, which creeps through the film with an ominous consistency that betrays the smooth surface for the chaos just beneath it. Ambitious in its scope, thoughtful in its presentation of Columbia’s history, and devastatingly honest, Birds of Passage is a magnificent examination of what it means to live in a larger world that has no understanding (or concern) of the past it’s hurrying into history.

Comments on this entry are closed.