[Rating: Solid Rock Fist Up]

[Rating: Solid Rock Fist Up]

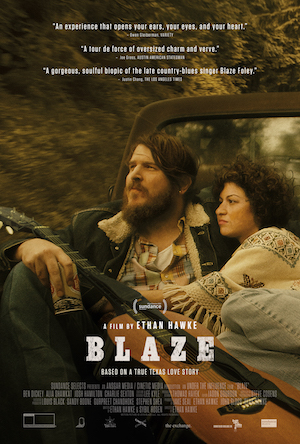

Blaze is a film that fits neatly within the classic tortured artist archetype: the pure of heart protagonist briefly ascends via their art before getting crushed by a world that isn’t ready for their groundbreaking form of expression. Through a tragic stew of substance abuse and/or mental illness, they burn brightly for a time only to die too soon, leaving a world scrambling to comprehend what it just lost. Whether it’s Amadeus, Bird, Pollack, Basquiat, or Sid and Nancy, it’s a story that filmmakers keep going back to. And while Blaze doesn’t break much new ground when viewed through this lens, it does succeed in telling an earnest story within this familiar framework.

Co-writer and director Ethan Hawke employs a lot of time jumps to tell his story about country and blues legend Blaze Foley (Ben Dickey), who enjoyed a small level of success during his lifetime, only to blossom into a certified legend following his untimely passing. The narrative is framed within three time periods: one that tracks Foley’s relationship with his muse, Sybil Rosen (Alia Shawkat), another that follows Foley on the last day of his life, and the third during a radio interview with two of Foley’s musical contemporaries. The three segments piece together the components of a story about a person yearning to find the perfect avenue for his unique brand of art, and how this struggle ultimately destroyed Blaze Foley.

This isn’t as easy as it might appear at first glance, because unlike Mozart, unless a person runs in Merle Haggard or Willie Nelson circles, Foley’s name and art isn’t something that rings out. Hawke’s script does a fine job of pulling out the understated, minimalist magic of Foley’s music, primarily through the story of that man’s relationship with Sybil. How the pair transforms from a content hippie commune couple into a broken shadow of what they once were comes off as genuine, and true to the spirit of the man’s songs. Foley’s inability to hold his liquor combined with a relationship that couldn’t endure the drama of alcoholism (which then leads to more drinking) is a familiar story, but feels earned, here.

It’s a credit to Dickey and Shawkat that this component of the story sells as well as it does, as both actors give nuanced, lived-in performances that sparkle with the radiance of familiarity despite the cliché set-up. The scenes from this segment imbue Foley with the humanity he desperately needs when he starts succumbing to drink and insecure rage, thereby forming the basis for the tragedy that is his life. Like so many artists of his ilk, Blaze Foley was a man that could have had it all if he’d just managed to get out of his own way, yet this was not his fate.

It’s a credit to Dickey and Shawkat that this component of the story sells as well as it does, as both actors give nuanced, lived-in performances that sparkle with the radiance of familiarity despite the cliché set-up. The scenes from this segment imbue Foley with the humanity he desperately needs when he starts succumbing to drink and insecure rage, thereby forming the basis for the tragedy that is his life. Like so many artists of his ilk, Blaze Foley was a man that could have had it all if he’d just managed to get out of his own way, yet this was not his fate.

This is something his friend and musical collaborator, Townes Van Zandt (Charlie Sexton), speaks to during his radio interview, the segment in Blaze that provides the structural framework for the narrative. In many ways, it is the laziest of the three bits, as it contextualizes in plain English what’s going on throughout Foley’s journey. It does tie in well with the final segment, detailing Foley’s last few hours, and is bolstered by an amazing performance by Sexton, yet it often feels like an unnecessary addition to a film with an aggressive 128 minute runtime.

A lot of attention is going to be paid to director Ethan Hawke and his work behind the camera, here. Overall, it is a commendable and entirely enjoyable effort by a guy with an obvious grasp on how to shoot a scene while making his actors look good in the process. Although some components of the script are a bit frivolous, and probably the result of a director reluctant to part with some damn fine (albeit indulgent) work, Hawke knows when to end a scene. For a movie that breaks the two-hour mark, Blaze never feels long, and this is a credit to Hawke’s ability to keep the picture well-paced and clipping along.

The measured use of light creates a shy, almost pensive ambiance that feels appropriate to Foley’s story, and the thematic and narrative ground covered, here. Indeed, this is the story of a man who hid in the shadows of life and seemed to make a conscious decision to stay shrouded there. Whether it was through booze or his own self-destructive tendencies, Foley did things his own way, and while the script does fall short when establishing a reason for this pent-up trauma (a great pair of scenes with Kris Kristofferson as Foley’s dad comes close), the consequences of this lifestyle are laid bare. The fact that this is a mostly-true story only adds to the tragedy of all of this, and adds some lead to the glove of Blaze.

The measured use of light creates a shy, almost pensive ambiance that feels appropriate to Foley’s story, and the thematic and narrative ground covered, here. Indeed, this is the story of a man who hid in the shadows of life and seemed to make a conscious decision to stay shrouded there. Whether it was through booze or his own self-destructive tendencies, Foley did things his own way, and while the script does fall short when establishing a reason for this pent-up trauma (a great pair of scenes with Kris Kristofferson as Foley’s dad comes close), the consequences of this lifestyle are laid bare. The fact that this is a mostly-true story only adds to the tragedy of all of this, and adds some lead to the glove of Blaze.

Steeped in tragedy, love, regret, and a giddy appreciation for art in its purest form, the film is a celebration of what makes art so special. Simultaneously liberating and the source for that which can most easily crush us, art is the ultimate double-edged sword: just as capable of cutting he who wields it as he who would be attacked. Hawke does a fine job retelling this age-old story using a mostly unknown subject, and as a result, Blaze does indeed sparkle.

Comments on this entry are closed.