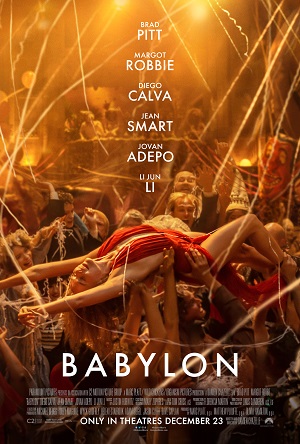

[Rating: Minor Rock Fist Up]

In theaters Friday, December 23

A dizzying kaleidoscope of debauchery, excess, and pre-code gonzo filmmaking, Babylon is less a movie and more a vibe. Alternatively a love letter to and repudiation of Hollywood’s earliest, basest nature, the film is at its best when it celebrates the raw insanity of its little corner of the history (and at its worst when it reveals the hollow characterization of its guides, there). Which sucks, really, because when Babylon hits, finding its balance of scene staging, acting, score, and purpose, it lands with explosive vitality with no cinematic peer…making the scenes when it fails in all these regards all the more painful.

Babylon opens in the underdeveloped land outside of 1926 Los Angeles, where studio lackey Manny Torres (Diego Calva) is doing prep work for a raging party set to commence that evening. This event is the audience’s introduction to silent-era Hollywood, which is populated by a rogue’s gallery of cowboys, musicians, vaudeville performers, runaways, and wild-eyed roughnecks who have all found an adoptive family within this relatively new scene. Throughout this 30+ minute cold-open, the audience witnesses unrestrained debauchery that’s Biblical in nature, with no vice, sin, or transgression left unexplored in a packed mansion full of the guilty.

During this party, we meet Nellie LaRoy (Margot Robbie), an unknown from out of town whose introduction is a car wreck into the mansion’s grounds. Another party attendee is Jack Conrad (Brad Pitt), the industry’s biggest movie star whose nearly 20 years at the top of the marquee represents the pinnacle of this era’s success on the big screen. Nellie and Manny, both desperate to break into the business, form an instant bond over cocaine, big dreams, and the fact that this party is their unofficial invitation into Hollywood’s inner-circle. Babylon follows all three as they take turns on different rungs of the industry ladder over the next few years, tracking their movements within a professional ecosystem on the verge of reinvention and upheaval.

This isn’t just the story of Hollywood’s transition out of the silent era into “talkies,” though: Babylon is part of writer/director Damien Chazelle’s ongoing examination of what it means to dream big and get everything you wish for. Whether it’s a music conservatory student entering the gauntlet of greatness, two 21st century Hollywood hopefuls balancing love against ambition, or an astronaut striving to move humanity into its next phase, all of Chazelle’s movies contend with this “careful what you wish for” trope. Babylon is no different, though its focus is less precise, and too often gets lost in the ecstasy of spectacle over substance.

Even so, Chazelle does a fine job during the movie’s first act setting up not just this world, but the kind of characters who inhabit it. Nellie’s entrance into the film, literally crashing the scene, is indicative of a lost time in the industry when a person could just waltz into Hollywood and land a studio gig in one day. None of these people grew up dreaming to be movie stars for the simple reason that motion pictures didn’t exist at that time, but like Gold Rush miners, they’ve all flocked to the new promised land to strike it rich, and are acting with the same devil-may-care attitude that exemplifies any new industry popping up on the fringes of society.

And in this regard, Babylon works and then some. These early scenes showing the unshackled chaos of the pre-code studio system where sets regularly burned, extras died, and asbestos filled in for snow (and fire suppression devices) are electric and capture the manic energy of the period and its players. It also serves as a fascinating snapshot of a time before minorities were elbowed out of the business, as Babylon carves out some time to explore the journey of jazz band leader Sidney Palmer (Jovan Adepo) and singer-actress Lady Fay Zhu (Li Jun Li).

Most of the middle portion of the picture also works well: showcasing the uneasy transition into the sound era in a studio set scene that is simultaneously fascinating, hilarious, and nerve-wracking. Having arrived at this place, Chazelle and Babylon don’t seem to know where to head next, though. It’s clear that the script is using the mountaintop structure, a-la Boogie Nights, with the steep rise and fall of this little world, but the movie is so big-picture focused that its characters recede into the background when they should be establishing audience currency in the back half. Indeed, by the time the new studio system and more sophisticated audiences start chewing up Manny, Nellie, and Jack, one finds it hard to care.

Having painted itself into something of a narrative corner, then, Babylon keeps doubling down on its descent, pushing the characters and the story into the darkness (literally and figuratively). It continues doing so until it crashes unceremoniously and gets the rushed exposition dump that might have saved the audience 30-40 minutes out of a painfully bloated three hour and change runtime. It ends (no spoilers) with a montage celebrating the magical escapism of cinema, yet most of the narrative leading up to it is so uniformly ugly and vapid that it makes one wonder why these people and their stories were the conveyance device.

Still, even amongst this lot, there is some character, some tender humanity: yet time and again it is buried under a fatalist blanket that refuses to allow any of this old guard through to the new era. It also doesn’t help that Robbie is blowing everyone else off the screen with her performance, with even Pitt suffering by comparison (it really is that good). Besides Robbie, the score by Justin Hurwitz is among the film’s consistent highlights, reminiscent of his “City of Stars” motif from La La Land, and just as warm and delicate.

Chazelle flirts with a stable narrative at times, using his three leads as a rotating chorus in support of each other, yet time and again he and the movie make way for a “wow factor” scene that betrays the larger piece. Far too long and with no idea how to put a bow on all of this, Babylon fizzles out with the same tragic whimper that characterizes its doomed characters. Worth seeing for the moments that shine (of which there are many), Chazelle and the movie’s 3rd act ultimately sell the larger effort short.

Comments on this entry are closed.