[Rating: Solid Rock Fist Up]

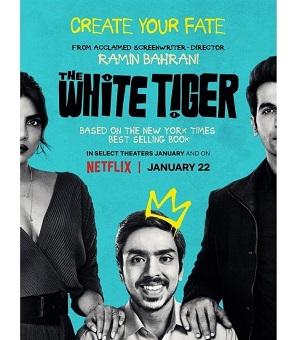

In select theaters and on Netflix January 22.

A gritty meditation on class, globalization, family, and destiny, The White Tiger is a film that is nearly as bold as its main character. Adapted from the novel of the same name by Indian author Aravind Adiga, it’s the story of one man’s struggle within and against an ageless system engineered for his exploitation and disposal, and has a lot to say about a rapidly evolving world uninterested in righting this wrong. The film’s strength lies in its ambiguity, however, for while the primary narrative sells the audience on the power of individualism, of a brutal bootstrap pull out of poverty, lots of folks need to get stepped on to make this happen.

Told through the narration of Balram (Adarsh Gourav), a 20-something north-Indian entrepreneur writing a letter to Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao in 2010, The White Tiger opens with a flashback to Balram in the backseat of a luxury SUV a couple of years before. This moment is the most consequential of Balram’s life, yet as he explains, it’s not the best place to start the story, so he recounts his early years in Laxmangarh, a small Indian village run by a regional landlord of sorts, nicknamed The Stork (Mahesh Manjrekar). Born into a lower caste, Balram becomes aware of the lopsided state of the world while still a boy as his father, and later his brother, fall victim to the region’s endless cycle of exploitation and familial obligation.

When Balram makes a play to get driving lessons so that he can become the chauffer for The Stork’s youngest son, Ashok (Rajkummar Rao), he does so not to escape this cycle, but to set himself up more comfortably within it. Born into a reality where a sort of indentured servitude is the best one can hope for, Balram feels lucky to sleep indoors, wear a uniform, and absorb the verbal and physical blows that come with his regular paycheck. The SUV incident glimpsed at in the opening minutes of The White Tiger brings the reality of this arrangement crashing down upon him, however, and challenges Balram’s already tenuous grasp on his place in the world.

Throughout the film, Balram keeps going back to an analogy he introduces about local poultry vendors keeping their animals locked up in rooster cages. He remarks that these roosters and hens see those around them getting slaughtered, yet never try to escape, saying, “They know they are next, yet they cannot rebel. They do not try to get out of the coop.” The SUV incident and the resulting fallout bring home the reality that even with his big chauffer come-up, Balram was never more than a very comfortable rooster in a cage that was just a little further back in the kill line than the others.

There’s a way out of the cage, but it isn’t pretty, and in a not-at-all veiled swipe at another Indian rags-to-riches tale, Balram sneers, “don’t think for a second there’s a billion rupee gameshow you can win to get out.” Director Ramin Bahrani, who also penned the screenplay, is juggling several themes and ideas with this story, and manages to develop all of them through the lens of Balram. Ashok and his wife Pinky (Priyanka Chopra), whose American roots are even deeper than her husband’s, represent the growing influence of globalization in 21st century India. They embody a conflicted duality to this movement, for they talk to Balram about the importance of his individuality (which does indeed inspire him), while representing an industrial movement whose very presence in the region relies on the exploitation of a cheap labor force.

There’s an element of performative allyship in the way Ashok and Pinky treat Balram, and after the SUV incident, all their talk to him about living his own life without the yoke of servitude reveals itself as hollow. Their relationship was always one of an exploiter and the exploited, and all of Pinky and Ashok’s Yankee wokeness goes out the window when the going gets tough. The exploitation comes from all sides, too, as Balram’s brother and grandmother demand their cut of his salary and his return to Laxmangarh to marry a woman pre-selected for him. Every element of his existence, from his family, to his employer, and even his government: all of it is manufactured to keep him in his rooster cage until it is time for his symbolic slaughter.

Bahrani shows that the escape isn’t the difficult part, it’s the moral jump necessary to accomplish the act that is tough. Another analogy that Balram deploys throughout the story is one of light and dark, and how India is divided between those who are exploited (in the dark) and doing the exploiting (in the light). Balram transcending his roots to become a successful entrepreneur (as seen through his present-day wealth and power) wasn’t the result of some plucky, harmless initiative: it takes more than this to flee the dark. Without going into spoilers, it should suffice to say that Balram’s escape from the rooster cages, from the darkness, comes with consequences, and no amount of kind behavior or reformed business practices once on top can wash this off his hands.

It’s a cruel, desperate, and violent world, and Balram’s place in it does little to help anyone except Balram and a lucky nephew with impeccable timing. Gourav has to carry the whole weight of this story on his shoulders, and with a lesser actor it might not have worked. Luckily for Bahrani and the film, Gourav is more than up for the challenge, and allows the audience to track Balram’s development from a wide-eyed, just-happy-to-be-here manservant to a jaded, desperate creature just hopeless enough to make the awful choice that is the key to his liberation.

Making good use of American hip-hop as a thematic soundtrack to the rebellious, outsider path Balram is tempted by (Fat Joe, Jay-Z, Gorillaz), Bahrani has crafted a complex, relevant, and faithful adaptation of Adiga’s novel. And while the second act drags a bit, and the third doesn’t quite know which ending cap it wants (and so keeps them all), the sum of its parts makes for a bracing drama that is light on its feet. Led by Gourav in a star-making turn, The White Tiger has teeth big enough to hold on long after the credits roll.

Comments on this entry are closed.