[Rock Fist Way Up]

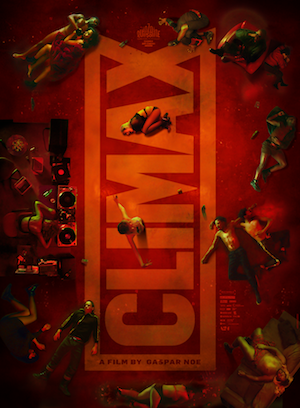

When you go see a movie by French provocateur Gaspar Noé (Irreversible, Enter the Void), it’s important to know that you’re likely in for a deeply disturbing experience. To say that his newest film Climax, a phantasmagoria of bodies bouncing off of each other in beautiful and horrific ways, is probably also his most mainstream doesn’t diminish that sentiment one bit.

I’m also using the phrase “go see a movie” because Climax begs to be seen on the big screen — huge and up close, with it’s throbbing backbeat front and center and it’s block-letter flashes of bold statements like “EXISTENCE IS A FLEETING ILLUSION” as in your face as Noé intends them to be.

The film is a perfectly structured series of stylistically formal set pieces. It features a team of 20 or so young modern dancers who are rehearsing in an abandoned school. They are about to embark on an international tour together and are celebrating their latest piece of choreography one night, but the film is about so much more than that.

As if imitating the birth-to-death and death-to-birth paradox of life, Climax begins with the ending of the movie and its end credits, soon crashing into a fixed shot of a strategically framed old CRT television that’s surrounded by books and VHS movies (Argento’s Suspiria, Zulawski’s Possession) that give us lots of clues as to the what’s in store for us and what’s on Noé’s mind. On the TV appear the supposed job interviews of the dancers who were eventually chosen by team manager Emmanuelle (Sofia Boutella). There’s inherent excitement, energy, and good-natured humor (something rare for a Noé film) in this sequence, which not only serves as a unique kind of character introduction, but also trains us to scan the frame for clues about the film’s themes.

From that static shot, cinematographer Benoît Debie (Spring Breakers; Enter the Void) leaps into the film’s centerpiece, a dazzling long-take protracted dance sequence that also teaches us to expect that the remainder of the movie will be very experiential. Debie’s camera wanders (steadily at first) from dancer to dancer as they verbally express the fears and insecurities that their confident dance moves hide so well.

“LIFE IS A COLLECTIVE IMPOSSIBILITY.”

Wth a statement like that appearing on the screen, yes, you can probably see where this is headed. Something changes within the group, and everyone’s feelings become heightened. Debie, whose camerawork so inventively portrayed a psychedelic drug POV in Noé’s 2009 epic Enter the Void, adds several new techniques to his repertoire here, and his camera’s swirling perspectives combined with the aural assault of the music reverberating in different rooms — is once again as close to mind-altering as cinema has ever been.

Whatever idealism the group was outwardly portraying begins to disappear, and things spiral out of control. Although the dancers come from a variety of backgrounds and cultures, what they go through in one hellish night is a microcosm of the big-picture experiences of life, writ large. Noé showcases all the external beauty, wonder, and hope that new opportunity can bring, and how — thanks to self-doubt and our own baser human instincts — those concepts are always just one thin wire away from chaos and madness.

Comments on this entry are closed.