[Rating: Minor Rock Fist Down]

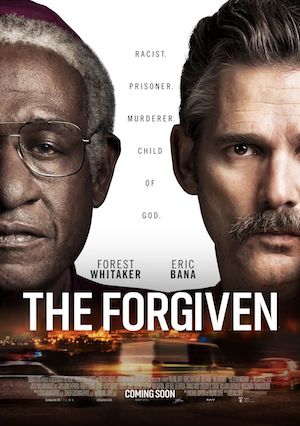

There’s an interesting movie floating around somewhere in the soup that is The Forgiven, but few of the necessary components are in place to bring it out. The film tells the story of Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s (Forest Whitaker) Truth and Reconciliation commission…or, no, actually, it is concerned with Tutu’s relationship with the incarcerated killer, Piet Blomfeld (Eric Bana)…wait, that’s not right, it actually focuses on a murder mystery involving police corruption and one mother’s quest to learn the truth about her missing daughter…well, except when the movie wants to be a hardcore prison drama that has little to do with any of this other stuff, so…shit.

Director Roland Joffe tries to tell so many different, competing stories in The Forgiven that none of them develop in any satisfying way, and instead undercut the focus that might have been applied to any of them. The film opens with two flashbacks, then hops forward into 1996, where the story is set during the early days of South Africa’s democratic government. The country is on the verge of tearing itself apart with racial violence, yet rather than set up war crimes tribunals to investigate the countless accusations of rape, kidnapping, torture, and murder, newly-elected president Nelson Mandela appoints Tutu as the head of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

The Commission’s mandate is to investigate apartheid crimes, and give the accused an opportunity to make a full confession. In short, if the victims, their families, and the Commission decide that a confession was made in earnest, it has the power to grant amnesty to the accused. One of the country’s most notorious criminals, Piet Blomfeld, reaches out to Tutu to see if he might be heard, which pits two men with wildly different morals and worldviews against each other. The ways in which these men challenge each other and encourage emotional and spiritual growth is one of the highlights of The Forgiven, yet Joffe’s movie is not content to explore just this.

A B-plot about a woman’s missing daughter, likely the victim of an apartheid death squad, keeps nudging its way into the narrative, as does a C-plot involving a prison gang called the 28’s, which operate in the same facility that houses Blomfeld. And just when the movie seems as if it couldn’t possibly bloat out any further, characters only tangentially related to the A, B, & C plots pop in from time to time to advance narrative elements that could have easily been carried by the established leads.

A B-plot about a woman’s missing daughter, likely the victim of an apartheid death squad, keeps nudging its way into the narrative, as does a C-plot involving a prison gang called the 28’s, which operate in the same facility that houses Blomfeld. And just when the movie seems as if it couldn’t possibly bloat out any further, characters only tangentially related to the A, B, & C plots pop in from time to time to advance narrative elements that could have easily been carried by the established leads.

And that’s just the problems The Forgiven has with its story. Forest Whitaker has the thankless job of portraying a globally recognizable and beloved figure who is as burned into the social consciousness as anyone alive today. The prosthetics and make-up do a decent job approximating the physical likeness of Tutu, yet Whitaker’s voice, size (Tutu is not a large man, and Whitaker absolutely is), and bearing don’t quite fit. His scenes with Bana, who is very good as Blomfeld, are the best of the film, yet they aren’t enough to elevate the effort beyond its baked-in limitations. Whitaker has to carry this movie as its lead, after all, so whenever his portrayal veers into imitation (as it sometimes does), the audience is shaken out of the drama.

On a technical level, there are other problems. Many of the scenes that take place outside have sound mixing issues, with dialogue recorded after the fact (ADR) not quite lining up with the actors in their scenes. Making matters worse, this dialogue is often clunky, and exposition-heavy, likely owing to the fact that the script is an adaptation of an existing play (‘The Archbishop and the Antichrist’). As a result, few of the film’s progressions feel earned, or developed in an organic way. Characters say aloud what they feel or think at any given moment, betraying the fundamental “show don’t tell” rule of filmmaking.

All of this adds up to disjointed, confused, technically deficient movie with uneven acting laid over subject matter that leaves little room for error. Decades of horrendous human rights violations drudged up generations of pain and despair when the South African apartheid ended, which led to a historic reckoning devoted to reconciliation and understanding rather than anger and revenge. An entire country had to learn how to come together and rethink deeply embedded notions of self as framed within the context of race and the nation as a whole, and to do so without tearing itself to shreds in the process.

All of this adds up to disjointed, confused, technically deficient movie with uneven acting laid over subject matter that leaves little room for error. Decades of horrendous human rights violations drudged up generations of pain and despair when the South African apartheid ended, which led to a historic reckoning devoted to reconciliation and understanding rather than anger and revenge. An entire country had to learn how to come together and rethink deeply embedded notions of self as framed within the context of race and the nation as a whole, and to do so without tearing itself to shreds in the process.

The Forgiven hints at this struggle (a scene early on with a scared and angry policeman interrogating Tutu is very effective), and how that ties in to the pain, fear, and frustration felt by both the white and black communities of South Africa at this time. Yet the script is never able to integrate this with the story it wants to tell about Blomfeld, or the missing daughter, or the prison drama side-story. To be fair, all of these threads are hastily tied up in the last ten minutes or so, yet “hastily” is the key word, here, for it all feels a bit tacked on, as if it is there simply to justify their existence in the story.

Opening this week in theaters and on VOD and Digital HD, The Forgiven tells an important story poorly, which sucks, because there is a lot of prescient, interesting stuff at play in the movie. Hampered by Whitaker’s uneven performance, and a script that doesn’t know how to tell the kind of story it wants to relate, the picture struggles under the burden of several competing narrative threads. An important movie, to be sure, it just isn’t a good enough one to do its subject matter justice. Its heart seems to be very much in the right place, however, so for that, perhaps The Forgiven can be forgiven.

Comments on this entry are closed.