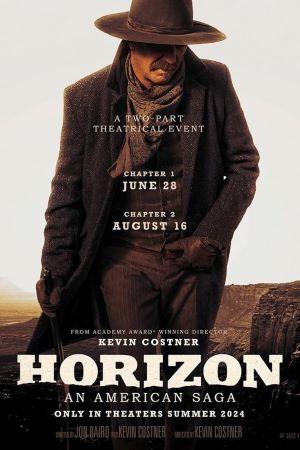

[Rating: Solid Rock Fist Up]

In Theaters Friday, June 28

“I’m going to John Ford the shit out of this thing.” -Kevin Costner (probably)

A fearless opening broadside for a massive story that assumes viewers have the balls to stick with it over the course of twelve-ish hours and 4 installments, Horizon: An American Saga – Chapter 1 is nothing less than astonishing. It’s rough going at times, with sometimes spotty acting clashing against the overly sentimental tone of a few set pieces, yet what co-writer/director/producer/co-financier Kevin Costner is going for, here, is crisp, clear, and stunningly concise for a 181-minute movie. Sporting the look of a wide-scope western with all the visual trimmings of the classics crossed with 21st-century narrative sensibilities, the movie is as vast as it is daring.

Costner and his script bounce between a few different locations, time periods, and character groups, starting with southern-Arizona territory circa 1859, where a local Apache contingent murders a trio of white surveyors. Three years later, a small community of settlers numbering about 100 has built a modest tent city in the same area, which a land speculation flier identifies as “Horizon.” This new settlement is likewise attacked by Apaches, leading the survivors to split into two factions: the larger one retreating to the relative safety of the nearby cavalry fort, the other forming a posse to hunt the natives responsible for the attack.

1859 also marks the start of a different plot thread, this one up in the Montana/Wyoming territories, where a woman shoots a sleeping man and steals (reclaims?) a baby from him. The man survives, and his sons, led by Junior Sykes (Jon Beavers), set out to find the perpetrator and the child. Three years later, this leads them to a confrontation with horse trader Hayes Ellison (Costner) and a different woman, Mary (Abbey Lee), who form an unlikely partnership to keep the child (and each other) safe.

Horizon then introduces yet another location and set of characters with a wagon train passing through Kansas, led by trail ‘Captain’ Van Weyden (Luke Wilson), who is struggling to keep a couple dozen families moving west and out of conflict. This host includes a dandy British couple, a family bearing the same name as one of the surviving Horizon clans, a pervy set of European immigrants, and others besides. In this story and all the others, the characters chase, consider, and/or contend with Horizon as not just a physical place/settlement, but as an idea tied up in uniquely American notions about Manifest Destiny and the siren song of the West.

People are going to say that the film is a throwback to an earlier time, a halcyon era of long-dead filmmaking: but that’s utter bullshit. No one has ever made a high-concept, long-arc narrative, multi-movie western before! If Dances with Wolves was Costner’s Hobbit, Horizon: Chapter 1 is his Fellowship of the Ring, his announcement that he’s blowing out his most cherished shit and injecting it with fucking nitro.

The audacity is astonishing, and not just in terms of the scope of the narrative. Costner sets this story just before/during the American Civil War, putting these characters at a figurative and literal crossroads at the same time as their country. The idea of Horizon is as much a character as any other in this story, and how the people in this world interact with that concept underpins the broader story writ large. Again, the settlement in southern Arizona represents more than just a place, it portends doom for the Natives, a chance at rebirth for the white characters, and a hell of a lot of question marks for everyone else.

There’s time given over to ideas of class, ethnicity, and gender in each of the stories, and while Horizon is coded as a decidedly white story, it doesn’t exist in that bubble alone. The film is interested in how the Native tribes are contending with this social and physical movement west and highlights the ways people of color and women fit into this story. There are a couple tough scenes that harken back to mid-20th-century “wild injun’” tropes (the Apache murder the shit out of some extremely white people) yet they serve to develop the larger story in an authentic way rather than bog it down in expired archetypes.

Visually, Costner uses the landscape of the western United States like a goddamned Howitzer, blasting the screen with achingly beautiful sky scapes, Monument Valley panoramas, and pine-crested valleys. Director of Photography J. Michael Muro isn’t shy about going wide on his establishing shots, showing where Costner’s bank account got got with fully built-out mining settlements, wagon trains, and the eponymous Horizon itself. Horses and their wranglers aren’t cheap, and neither is casting and dressing a couple hundred actors in period-appropriate costumes, yet Costner doesn’t seem to care.

And why should he? If nothing else is clear throughout its 181-minute runtime, it is that Horizon Chapter 1 is a safe space for bold filmmaking free of studio notes and multi-quadrant planning. Like any good piece of art, it is the product of a singular, confident vision that knows what it wants to be and pursues that end with a devil-may-care attitude. Standing somewhere on the cinematic spectrum between Orson Welles and Tommy Wiseau, Costner has planted his flag and seems willing to die fighting at its base in a last stand that would make Custer blush. It’s an old-fashioned image, and daring, but what is Horizon if not that?

Comments on this entry are closed.