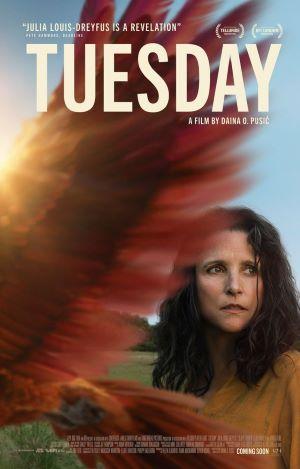

[Rating: Solid Rock Fist Up]

In Theaters Friday, June 14

A 21st century fable about loss and grief that harkens back to humanity’s earliest creation/destruction mythologies, Tuesday probes the literal struggle, the actual fight, of life and death. Conceptually simple, yet bold in every other arena that matters, the film considers what it means to die from every angle, pondering it from the perspective of the patient, the aggrieved, and even the vessel of death itself. There’s still a lot of questions by the closing credits, yet again, in all the places where it matters, the story resolves itself and has an emotional thru line with a meaningful beginning, middle, and end.

Filmmakers have had a lot of fun personifying death over the years, jumping between Max von Sydow to Brad Pitt with a dash of William Sadler and a few others between (and since). Tuesday supposes the elemental force of nature is a Macaw Parrot that can shrink, grow, appear, and disappear at will. Death (voiced by Arinzé Kene) is bouncing from job to job with a constant, piercing ringing in his feather-shrouded ears beckoning him to ever more clients when he happens upon a chronically ill young woman in London named Tuesday (Lola Petticrew).

Just before her “release,” Tuesday shares a joke with the parrot and offers the oil-stained creature a bath: a rare gesture of kindness that endears Death to her as he laments that, “All beings in the world fear and despise me.” Death and Tuesday bond over the idea of just one day without pain, connecting over Ice Cube’s “It Was a Good Day” and a vape pen before Tuesday asks that her departure be delayed until her mom gets home. The request is granted, yet when the mother, Zora (Julia Louis-Dreyfus), returns, there’s no goodbyes, just arguments and literal fighting against nature’s calling.

To say much more would ruin the process of discovery as Tuesday gets through its second act, which is stocked with a couple of twists that are equal parts predictable and shocking. Zora’s refusal to accept her daughter’s fate, even in the face of personified Death itself, serves as the backbone of the picture, yet it’s more than just an allegory for the process of letting go. Tuesday’s delayed departure is a pebble whose ripples disrupt the very fabric of existence, and writer/director Daina Oniunas-Pusic is interested in how this speaks to the A-plot’s particulars on both an emotional and practical level.

It’s also telling that the best parts of the movie occur in between the most consequential scenes, like when Tuesday and Death discuss the latter’s run-ins with historical figures like Stalin and Jesus, or when Zora and her daughter have a difficult conversation about the former’s career and finances. In the grand scheme of what is happening in Tuesday, these might seem like trivial moments, yet besides mining the best comedy and drama of the piece, it demonstrates Oniunas-Pusic’s complete mastery of the story as a vessel for deeper truths. These interstitials provide more than just texture to these characters and their world, they speak to the picture’s broader themes about how all creatures, even elemental forces of nature, feel, love, hurt, and grieve.

The visual look of Tuesday with its over-emphasized shadows and low lighting reflects its thematic intentions, bringing its characters out into the sunlight only when they have a respite from the oppression of their lives. Zora, who spends her days selling items and heirlooms to pay for her daughter’s medical care, slinks around in the dark crevices of daytime London, even going so far as to fall asleep when she attempts to get a little fresh air in a park. In an ironic twist, Death’s arrival in Tuesday’s life comes during a private moment in a sun-soaked garden, and many of their encounters remain basked in radiance as a reflection of their bonding over shared trauma.

Petticrew, JLD, and Kene are the MVP’s here, though, and each imbues their character with a dump truck’s worth of lived-in history colored with pain, squelched joy, and resigned apathy. JLD balancing Zora’s avoidance of her daughter early on against her pathological need to hold on to her after Death’s appearance is masterful and demonstrates a complicated range of emotions that make sense despite their seeming contradiction. Kene is also as funny a version of Death as any that has appeared on-screen, and while he isn’t a joke machine by any stretch of the imagination, his dry wit, direct nature, and sarcasm are a boon to a picture with more than its fair share of heavy scenes.

Every human culture has worked up some form of Death as a personified entity, whether it is the buffalo-riding King Yama from the Hindu scriptures, the star-swallowing Mictecacihuatl of Aztec mythology, or the bad-ass and extremely metal Pale Horseman in the Book of Revelation. None look like a Macaw Parrot, or each other, yet all represent an immoveable force greater than the will of any mortal who thinks (incorrectly) that their needs stand any chance against the larger forces at work around them. Tuesday considers this age-old question from not just Zora and her daughter’s perspective, but Death’s as well (and not just in a cheeky “I’m on vacation with Anthony Hopkins” sort of way). Although the movie doesn’t break new ground in this age-old conversation, like the use of a tropical bird as the mythological force of nature, it is a fun, new take on an ancient, endlessly relevant story.

Comments on this entry are closed.