[Rating: Solid Rock Fist Up]

Streaming on Netflix Dec. 9

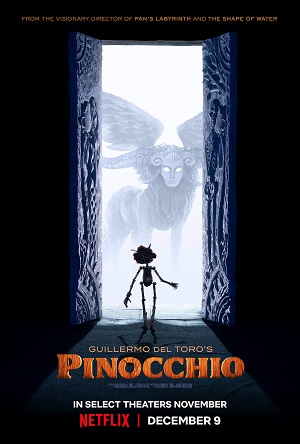

When Walt Disney got his hands on this story, a whole friggin’ island of children turned into donkeys via an animation sequence that still makes grown men reared on Liveleak and 4Chan squirm. It’s a tough act to follow, but Guillermo del Toro has spent the last 30+ years buttering his cinematic bread by smashing the whimsical against the cruel realities of this world, so it should come as no surprise that his take on Pinocchio is likewise equal parts terrifying, poignant, and beautiful. Employing gorgeous stop motion animation techniques to craft his version of the old fairy tale, del Toro reimagines all of this as only he can, sifting through the strands of heartbreak, hope, childish wonder, and social relevance to tell an old story in the freshest possible way.

Framed through the narration of Sebastian J. Cricket (Ewan McGregor), Pinocchio unfolds with linear ease, starting in early 20th-century Italy, where woodcarver Geppetto (David Bradley) lives in happy contentment with his adolescent son, Carlo (Gregory Mann). Studious, polite, and kind-hearted, Carlo dies unexpectedly, leaving his father heartbroken and mired in despair. Years pass in untethered misery before Geppetto fixes on an idea to carve a puppet in his son’s likeness: an act that so saddens a magical wood sprite (Tilda Swinton) that she grants life to the wooden boy (also voiced by Mann).

Formerly a resident of the tree out of which Pinocchio is carved, Cricket objects to his home’s radical renovation, and strikes up a deal with the supernatural fairy for a granted wish in return for employment as the new boy’s conscience. With the wooden boy alive, and his insect guardian at his post, Geppetto wakes the next morning to one hell of a surprise, which, like most developments in this movie-musical, is smoothed over by a song. And while certain details about the story are changed to fit the setting and thematic undercarriage, this first act demonstrates the relative fidelity del Toro’s version maintains to the popular 1940 Disney classic.

This isn’t just a reboot, though: far from it. While the Disney version of this story focused more on themes of obedience, devotion, and duty for its young audience, del Toro and co-director Mark Gustafson are more interested in what this fable’s implications are for the adults in the audience. Much like Dr. Frankenstein, Geppetto and the wood sprite craft new life out of whole cloth without any consideration for the consequences, leaving the creation to largely fend for itself. The boy, so enamored with the newness of everything, can hardly be blamed for the unbounded enthusiasm that sees him crashing into a world not ready for him. And while the familiar notes of the story still poke fun at the wooden boy’s rambunctious and impetuous nature, far more judgment is reserved for the community that fails him.

Also, by pulling this out of the fantasy setting and into the historical reality of Mussolini’s fascist Italy, del Toro adds stakes to the fantastical. Again, owing largely to the more adult-oriented themes of the narrative, this telling of the fable challenges Pinocchio to parse out what it means to be a “good” boy not just as a reflection of proper child rearing, but as a member of a family. The character of Podesta (Ron Perlman), the fascist government functionary obsessed with militarizing the town’s youth, goes a step further, and asks the audience to consider what it means to be “good” within the larger framework of a community: adding a fascinating layer to the story.

The music by Alexandre Desplat is at its best when leading with the innocent, crackling timbre of Mann’s young voice, which keeps the effort from veering too far off into the darker realms that populate the movie’s corners. Bradley is less successful in this regard, though the film wisely deploys his voice and those of his co-stars where they are at their best in most instances (straight dialogue). There’s a tenderness to this incarnation of the wooden boy, which again, focuses less on his impulsive nature and more on the community that fails him, and the stop-motion work feels perfectly suited to this more intimate portrayal.

Like most of del Toro’s pictures, no emotional stone goes unturned in Pinocchio: where outright evil does exist, but shards of humanity still glow like the dying embers of a fire, just waiting for compassion to breathe life into them. This take on the old fable is both entertaining and insightful, and presents the story in a visual format that is altogether new for this tale yet ideally suited for this telling. Top notch voice work, stunning animation, and a thoughtful reconsideration of the themes justify this one as more than just a reboot, but rather a fresh new take on a familiar and consequential story.

Comments on this entry are closed.