[Rating: Solid Rock Fist Up]

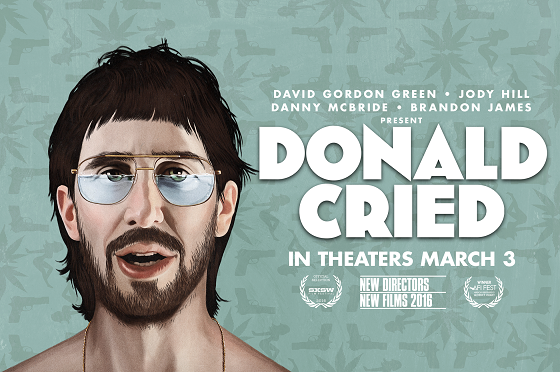

Movies about people coming home to face a deliberately forgotten past have been around almost as long as the medium itself, but few examples rival Donald Cried in the sheer force of will of that past struggling against erasure. Writer-director Kris Avedisian has crafted a film that’s an uncomfortable meditation on what it means to disconnect from that part of yourself that you’re ashamed of and want to forget, and what happens when that piece of you is personified and refuses to disappear.

Donald Cried opens with its lead, Peter (Jesse Wakeman), getting out of a cab in a snow-packed Rhode Island suburb. As he exits the vehicle, Peter realizes that he lost his wallet on the bus that brought him to town, and despite pleas with his driver, Peter can’t convince the man to take him back to the terminal to find it. In town to settle the affairs of his recently deceased grandmother, Peter is stuck without any I.D., money, or even a car. Unable to get anyone he knows to wire him some cash, Peter is left with no other alternative but to walk across the street to call on a childhood friend he has avoided for the better part of two decades.

When the audience meets this friend, Donald (played by Avedisian, who wrote himself a softball with the role and knocks it out of the park), it becomes painfully clear why Peter has kept his distance. Donald seems to have stopped maturing at around 15, and while Peter has grown into a serious Wall Street type, his childhood friend’s biggest news is that he recently met his favorite porn star. Donald agrees on the spot to drive Peter around town to settle his grandmother’s affairs, yet it’s clear that the favor comes with just one caveat: Donald.

Donald is desperate to reconnect with Peter, probably the last (only?) real friend he’s had. And while Donald comes off as something of a man-child, his street-smarts have advanced beyond the 15 year old level. Indeed, although he’s about as mature as a high school sophomore, the guy has been around long enough to know when he’s being lied to, or avoided. Using something of a Columbo approach, Donald confronts Peter on some social media dickery, and manages to keep his old friend from ditching him despite several concerted efforts. As the two old friends spend the day together, Donald holds onto Peter tighter as his friend works harder and harder to break free of that grasp.

Donald Cried sticks its landing at nearly every turn because it refuses to side with either Donald or Peter, who take turns being awful. Although Donald is an insufferable menace with no social I.Q. or tact, Peter comes across as equally selfish and cold. As it concerns their friendship, both have sins to atone for, and while Peter is content to skim the surface of this history, Donald insists on diving right back in for a few laps. These two men used to be best friends, and the only way they can get back to that place in Donald’s eyes is to physically wade through their history together. As they drive around town running errands, they meet forgotten acquaintances, revisit old haunts, and relive memories Peter is eager to forget: all to Donald’s delight.

As Avedisian’s movie progresses, the humanity within both Peter and Donald seeps through, and allows for a few humbling moments for both men. One scene in particular where Donald talks about a previous relationship and custody battle paints him as a man on the verge of an emotional breakthrough, yet without the moral encouragement to make that happen. Donald is a mess, to be sure, but it seems plausible that he might be less of one with someone like Peter in his life. And while it’s questionable whether Peter would enjoy a similar benefit from Donald’s continued friendship, by the end of the film, there’s an argument to be made about what humanity exists in the prodigal son that wasn’t there at the beginning. At its core, Donald Cried is about what people lose when they abandon their past, and what folks have to both risk and gain by dredging it back up to the surface.

Avedisian does great work behind the camera, yet the picture owes most of its success to the performances. Wakeman plays his part with a halting, screaming-on-the-inside intensity that allows him to say a lot while speaking very little. It’s easy to identify with Peter while still sighing at his assholery, a tricky feat to be sure, and one Wakeman deserves all the credit for. Yet none of this works without Donald, who has the unenviable burden of being both insufferable and the heartbeat of the picture. Avedisian lights up the screen when he’s in frame: his wide-eyed, childish glee bursting through every seam of his face. There’s a sadness floating just beneath the surface of his existence, however, and the picture works because it tries to understand this rather than exploit it for the sake of Peter’s story.

A brisk film at just under 90 minutes, Donald Cried feels like the two-headed love child of Manchester By the Sea and the Trailer Park Boys. It’s about loss, the reconciliation of past failures, and northeastern rubes with all the class of a carnival barker. Out now at Screenland Armour, Avedisian’s film is worth seeing as much for what it says as for what it doesn’t.

Comments on this entry are closed.