Ex Machina does what excellent science fiction always does. It uses the tenets of the genre to pose difficult questions about our human existence.

Writer and director Alex Garland is not new to thoughtful storytelling, nor is he inhibited by genre. From his existential exploration in Sunshine, one of three collaborations with Danny Boyle, to his man against the system adaptation Dredd, Garland sees opportunities to explore specific philosophical questions through action, horror, or science fiction.

In Ex Machina, Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson), an employee at the global search engine, and Google stand-in, BlueBook, wins a contest and gets to spend a week at the private estate of BlueBook CEO and billionaire tech mogul, Nathan (Oscar Isaac). Very quickly we find out that this is no lavish vacation, but an intriguing opportunity for Caleb.

Nathan believes he may have cracked artificial intelligence once and for all. In a sealed room sits Ava (Alicia Vikander), a fully functioning humanoid robot that may be the first human-created sentient being.

Issues of consciousness, understanding, and mimicry all follow. Even the issue of Ava’s perceived gender, and her seeming awareness of her own sexuality come to the surface. How can they not? When Caleb feels not just an intellectual connection but sexual desire for a humanoid robot and Ava appears to return his affections, more than a few philosophical and ethical questions arise.

Issues of consciousness, understanding, and mimicry all follow. Even the issue of Ava’s perceived gender, and her seeming awareness of her own sexuality come to the surface. How can they not? When Caleb feels not just an intellectual connection but sexual desire for a humanoid robot and Ava appears to return his affections, more than a few philosophical and ethical questions arise.

But don’t get dazzled by the seamless special effects, or the wash of red and blue lights á la sci-fi design of the mid 1970s. Ava’s mechanical form allows Garland to talk openly, safe from the gnashing teeth of those who may bristle at more apparent and didactic filmmaking. This film is mythology. Ava, Nathan and Caleb are players in an allegory.

It is no accident that the two main human characters are male, while the sole robot is female. Ava is not allowed outside of her maze-like prison. She has never seen the world beyond her room. Caleb, her would be hero, cannot touch or directly interact with Ava. He is forced to talk to her through the glass walls of the observation room. Nathan, part Minotaur, part Minos, stands above Ava, controlling her as a possession and adversary.

It is no accident that the two main human characters are male, while the sole robot is female. Ava is not allowed outside of her maze-like prison. She has never seen the world beyond her room. Caleb, her would be hero, cannot touch or directly interact with Ava. He is forced to talk to her through the glass walls of the observation room. Nathan, part Minotaur, part Minos, stands above Ava, controlling her as a possession and adversary.

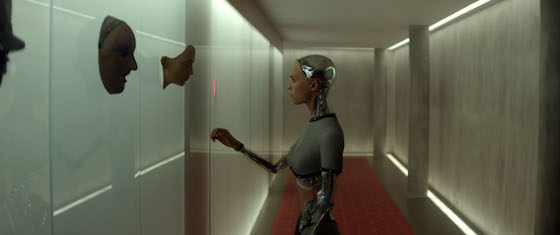

Ava’s body, though shapely, is visually mechanical. Her first impulse, as her attraction to Caleb develops, is to clothe herself. She has a shapeless calico dress and an awkward poorly trimmed wig. She is a child and also her own Barbie doll. Caleb sees Ava’s sexual understanding as childlike and naïve. He wants to protect her. He wants to save her.

Nathan, as captor, and Caleb, as savior, both see Ava as an object of control and desire.

Nathan, as captor, and Caleb, as savior, both see Ava as an object of control and desire.

So what of Ava? What does she think?

To discuss this too openly would be to give away all the surprises Ex Machina offers, but there is one moment that is telling, and worth discussion.

When Ava is able to cover herself in a synthetic skin, when she is finally able to become, at least visually, an anatomically intact cisgendered woman, she is outside of the reach of both men and surround by mirrors. She is naked, but her body exists for her alone.

And if these discussions of sexual identity, and feminism bother you, just remember, this is only a story about a robot and two computer programmers.

And if these discussions of sexual identity, and feminism bother you, just remember, this is only a story about a robot and two computer programmers.

By putting questions of gender, identity, personal motivation, and survival on to a robot and her human captors, Garland can give the viewer a safe distance from which to ponder these very human issues. Science fiction offers perspective to these human questions, when real life does not.

Comments on this entry are closed.