Listening is a skill that few people master, but the men of the Meyerowitz family are particularly awful at it.

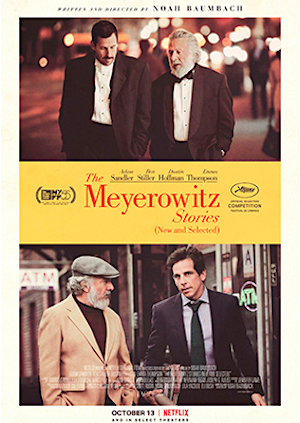

There’s probably no one worse at listening than recently retired art professor Harold Meyerowitz (played by Dustin Hoffman), the self-centered patriarch of writer/director Noah Baumbach’s latest NYC-set dramedy The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected), streaming on Netflix now. We see this in the second act, as Meyerowitz’s son Matthew (Ben Stiller) tries to talk to him about important financial matters, but Harold talks over him at every turn—obliterating the idea of the word “turn.”

Harold does the same with his other grown-adult son Danny (Adam Sandler), though he’s even more cruel and dismissive. All three of the Meyerowitz men are varying degrees of dismissive of Harold’s daughter, Jean (Elizabeth Marvel), although they seem to be aware of this as if it’s an accepted family dynamic.

The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected) returns to the artistic-cultural NYC world explored in Baumbach’s last two NYC dramedies, While We’re Young and Mistress America. And the director’s newest release is most certainly in the mold of his breakout 2005 film, The Squid and the Whale, a semi-autobiographical drama about a sniping family of Manhattan intellectuals. What is remarkable in this script is how much sympathy Baumbach generates for his characters, who in lesser hands would be one-dimensional brutes. Hoffman, Stiller, Marvel, and especially (I can’t believe I’m writing this) Sandler are up to the task, creating memorable portraits of insecurity that will linger long after the closing credits.

It’s appropriate that The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected) has a literary mouthful of a title, not just because of its setting, but because it’s initially structured as a set of semi-self-contained short stories, concentrating on one relationship at a time. Near the end of the movie, these storylines converge in a hilarious and emotional climax that’s not unlike the endings of Baumbach’s other NYC dramedies.

One could accuse Baumbach of repeating himself, but when the writing and directing is this sharp, who cares? The neuroses and contradictions of the Meyerowitzes go beyond their specific milieu and become relatable to anyone who’s had a difficult relationship listening to or being heard by their family.

This review is part of Eric Melin’s “LM Screen” column that appears in the winter 2017 edition of Lawrence Magazine.

Comments on this entry are closed.