[Rating: Swiss Fist] (complete neutrality)

[Rating: Swiss Fist] (complete neutrality)

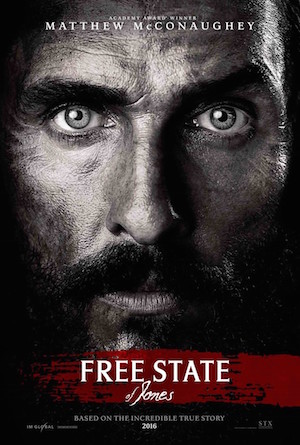

Early on in Free State of Jones, the Civil War drama starring Matthew McConaughey as polarizing Confederate deserter Newton Knight, the movie suddenly flashes forward 85 years to a courtroom. A white man is on trial, accused of being one-eighth black.

It’s a bold narrative move, and it tips writer/director Gary Ross’ intentions early on: Free State of Jones will not be a 100% historically accurate snapshot in time—it will have epic span and portray Knight’s myth through the lens of today’s social climate.

Was the real Knight driven to lead a scrappy army of Mississippian men against their own Confederate Army by a sense of righteousness against the cause of slavery? He only ever gave one interview, but this can be inferred from the five interracial children he fathered to his deeding 160 acres of land to his common-law former slave wife.

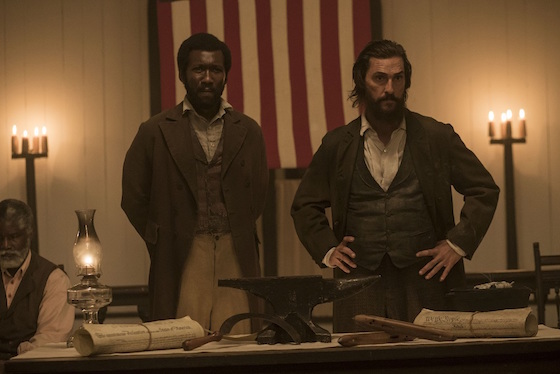

The movie’s unwieldy structure makes it a tough sell, but McConaughey’s Knight comes to this opinion slowly. His first inkling of rebellion comes from outrage over a law that exempts rich slaveholders from service in the Confederate Army for every 20 slaves owned on a plantation. The “rich man’s war, poor man’s fight” is a classic war trope with renewed relevance these days. The problematic “white savior” character (a Knight by name no less) is also a staple of socially-conscious films. Ross is aware of this as well, and to counterbalance it, he creates a fictional supporting character—a former slave (Moses, played by Mahershala Ali)—who has agency, and whose arc isn’t sugarcoated.

I admire the scope of Ross’s vision and his efforts to clearly convey a story with so many thorny issues. Does the film simplify many of them? By nature of a two-hour 20-minute running time, yes. (Ironically, the movie feels too long, but the story deserves the scope of a miniseries.)

Free State of Jones is a bumpy, imperfect tale of a troubling time in U.S. history, but it doesn’t burn with the urgency of say, 12 Years a Slave or Selma. As Selma acknowledged MLK’s extra-marital affairs, maybe Jones should have mentioned Knight’s additional nine children with his other (white) wife as well. Maybe clarity isn’t what this story needs, and there should have been more shades of gray (grey) than the ones on Confederate uniforms.

Sidenote: For a fascinating breakdown of the fictions that Ross created in Free State of Jones vs. the real story, check out freestateofjones.info—a breakdown of the entire film, written by Ross himself. It’s instructive not just to learn more about the historical “truth,” but to analyze the conventions and structures of message filmmaking and the limitations of feature-film storytelling.

This review is part of Eric Melin’s “LM Screen” column that appears in the fall 2016 edition of Lawrence Magazine.

Comments on this entry are closed.