[Rating: Minor Rock Fist Down]

French Exit is playing in theaters in limited release.

Less of a film and more of a collage of character quirks mashed together into something resembling a coherent narrative, French Exit tries (and fails) to skate by on eccentricities alone. Adapted from the book of the same name by Patrick DeWitt (who also penned the screenplay), what few characters the movie invests in do little to move the emotional needle of the story, and are sidelined time and again by a raft of supporting players who seem to exist for chuckles and little else. Lethargically paced and cut together like a late-season T.V. clip-episode, French Exit has a few moments where its characters approach intriguing, yet they’re lost in a story that doesn’t seem to know how to make use of them.

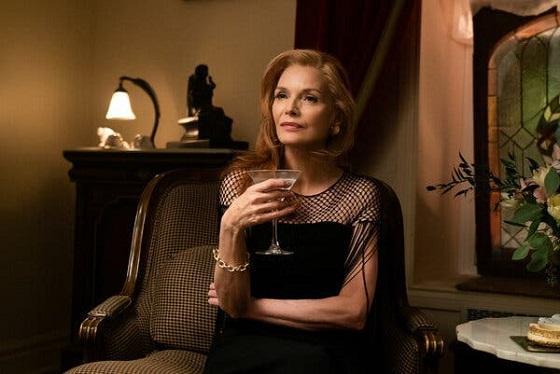

On the face of it, the plot is straightforward enough. Widowed Manhattan socialite Frances Price (Michelle Pfeiffer) learns early in the film that she has just finished burning through the remaining balance of her estate’s funds and must now strike out on her own to make ends meet. Selling her jewelry, art, and other assets net her a small nest egg, but she’s got no place to live and no concept of how to support herself or her 20-something son, Malcolm (Lucas Hedges). A friend, Joan (Susan Coyne), offers her Paris apartment to Frances and Malcolm so the pair can figure out their next steps, so with no better ideas available, mother and son set sail to Europe for an adventure.

The whole thing has a sort of low-key Wes Anderson aesthetic, in that it is a 21st century story populated by characters who seem stuck in the 1960s or 70s. People travel on cruise liners, write postcards, hire P.I.’s, and shop with cash, and while it does position Frances and Malcolm as displaced within the context of their story (i.e., they’ve been rich enough to avoid modern reality), the story never really intrudes on their bubble. Throughout French Exit, Frances trades barbs with waiters and lonely neighbors, yet the world never seems to encroach on her little fantasy. As the fallen socialite peels off €100 notes in one last parade of privilege and wealth, quirky moments litter the film, yet none of them come together to engage the audience in a way that develops the characters or a broader set of themes.

It’s not enough that Malcolm is listless and devoid of inspiration, or that Frances is utterly unconcerned with the whispers of a rumor mill that has a lot to say about her husband’s demise. These are flavor notes, not the narrative entrée the film seems to think it is. Instead of exploring the flaws and hypocrisies of these two leads, the film keeps diverting to add quirky texture to their surroundings, throwing in a clairvoyant con artist (Danielle Macdonald), an attention-starved American expat (Valerie Mahaffey), an honest private investigator (Isaach De Bankole), and a talking cat (Tracy Letts). The combination of all offer a few chuckles and do reveal a richer side to Frances, yet their combined presence feels like a distraction rather than the grand character tapestry it seems to be reaching for.

A side-plot about Malcolm’s inability to commit to his girlfriend (Imogen Poots, who is utterly wasted in this film), further weigh down the story, and is resolved in the most preposterous moment in the film: an amazing feat considering there’s not one, but two seances in this picture. To her credit, Pfeiffer does her best to anchor the larger effort with her steely patrician vibes, which pulsate off the actress with a seemingly effortless series of shrugs and poses. Frances is a woman whose wealth has allowed her to move through life with a genuine disregard for the opinions of anyone else, and yet she still manages to convey a private and profound affection for her son in her more guarded moments. This balance of fierce maternal warmth mixed with an icy, impenetrable exterior make for a riveting performance whose magic is snuffed out by the poorly conceived side acts mugging for attention all around it.

And that’s the problem, aside from some gorgeous cinematography, there’s little else to hold one’s attention throughout French Exit aside from Pfeiffer. Hedges is making a choice to play Malcolm without any shred of charisma or purpose, and while it works within the context of his journey, it’s a bore to watch. There are a few moments where the deep, largely unspoken bond between mother and son shine through, yet this relationship gets sidetracked by the nonsense surrounding the lost cat or Malcolm’s ex-girlfriend drama.

Whether it is a script that can’t quite manage to transfer the enchantment of the novel’s eccentricities, or the direction of Azazel Jacobs, who just can’t seem to assemble any of this into something that reads on-screen, or even the lifeless performance of Hedges, who is all but daring the audience to fall asleep, French Exit just doesn’t come together. Pfeiffer is delightful as the fearless, past her prime blue blood with nothing to lose, yet even her character, the most fleshed out of any in the picture, isn’t entirely well-conceived. For a woman whose one redeeming feature is her unshakable maternal instincts, she doesn’t seem that concerned with what might become of Malcolm once the money she’s so frivolously spending runs dry. Oh well, at least they worked the weird, unexplained, unearned slumber party into the third act. An odd choice, to be sure, but for a movie that consistently swerves away from substance to dabble in quirkiness, at least remains on-brand to the bitter, not at all satisfying end.

Comments on this entry are closed.