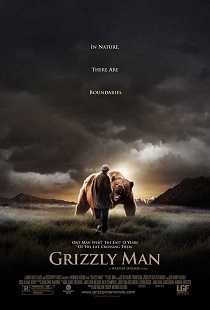

Knowing that one of legendary director Werner Herzog’s (“Aguirre: The Wrath of God,” “Fitzcarraldo”) favorite subjects is the futility of man to overcome nature, I went into his newest documentary “Grizzly Man” expecting a sobering story of a conservationalist do-gooder who tempted fate one too many times and ultimately lost out to nature.

Knowing that one of legendary director Werner Herzog’s (“Aguirre: The Wrath of God,” “Fitzcarraldo”) favorite subjects is the futility of man to overcome nature, I went into his newest documentary “Grizzly Man” expecting a sobering story of a conservationalist do-gooder who tempted fate one too many times and ultimately lost out to nature.

What struck me about halfway through one of the title character’s bizarre rants was that Herzog is also equally attracted to sheer madness.

“Grizzly Man” is an absolutely fascinating portrait of humanity at its most brutally honest, and is so much more than merely a cautionary tale. Timothy Treadwell slept with a teddy bear. He wanted to be a bear, or at least an animal. I didn’t say it, he did, on videotape that he shot out in the Alaskan wilderness, where he lived the last thirteen summers of his life. He claims he was living among the bears, completely unarmed, in order to protect them. One local resident interviewed by Herzog says that by living among them, he was making them more dangerous, crossing a line that had been respected by natives for years.

In October 2003, he and his girlfriend were mauled and eaten by a bear near their campsite in Alaska’s Katmai National Park and Reserve. They were the first known victims of a bear attack in the park.What starts off as a nature documentary featuring up-close, amazing footage with these fierce creatures begins to run off the rails pretty quickly. Herzog shows us the footage that Treadwell eventually wanted to use for his own wildlife documentary, but not quite as the man intended it to be seen. Treadwell kept the camera running between takes, and the raw footage between his narration is by turns confessional and just plain wacky.

Certainly Herzog is as captivated by the danger of the moment as the viewer is, but what materializes because of his choice is not an informational piece about bear habitat, but the paranoia and loneliness of one very troubled man.

The same technique is used in the interviews of Treadwell’s friends and family. The medium of film is subjective, and documentaries by nature, are artificial. People act different when they know a camera is filming them, and Herzog’s extended takes not only illuminate Treadwell’s on-camera persona, but shows the difference between what his interviewees want to project and their own insecurities about the “grizzly man.” As the coroner goes through the lurid details of the bodies’ conditions, a glint appears in his eye. Is it a revelation, a window to the man’s soul? Or is it a minor uncomfortable moment when his enthusiasm went a little too far? You be the judge.On that fact, Herzog lets the viewer decide, but not on all of them.

The director’s voice-over narration will be an annoyance to many people who see this movie. Although people like to believe in objectivity, the editing process itself inherently builds a “story.” The director chooses what he wants you to see in what manner he will present it. Usually, however, the narrator will refrain from out-and-out editorializing. This is not the case with Herzog. He’s been toying and teasing the audience with the ambiguousness of many images and interviews, but every now and then he comes right out and offers his personal take on the footage he is showing you.”This is where I differ from Treadwell,” he says, over an unguarded moment where Treadwell discusses the “harmony of nature” into his camera lens. Herzog goes on to offer a darker opinion; that nature is indifferent and its disposition is something closer to murder.

Such candor is nothing for a Michael Moore film, but it’s jarring when it only briefly interjects on the action. I defend the director’s right to say what he wants, and believe this film as a whole benefits immensely from the eccentricities of its maker, offering insights that others might have passed over as “unjournalistic.”At the heart of “Grizzly Man” is the amazing raw footage of a Timothy Treadwell living out on the edge of wilderness and his own sanity. A former actor who claims that he lost the role of the young bartender on “Cheers” to Woody Harrelson, Treadwell always wanted to be a star. After a bout with alcoholism, Treadwell turned to the bears, and credits them for saving his life and giving him purpose.

Ironically, living with the bears made him (in)famous enough to make an appearance on the “Late Show with David Letterman.” It is in the moments that he is all alone and talking to the camera that he unknowingly reveals so much. Pinned down in a tent by a sudden torrent of rain, Treadwell seems to be the happiest he’s ever been. He had just crossly prayed at and not to, “God, Jesus, that Christ guy, Allah, or Hindu floating thingy,” screaming at the top of his lungs for more rain so the bears he loved so much could feed on another salmon run up the river. So there he is, crouched down with the tent collapsed over him and a big smile on his face. The rain came, miraculously. He got his wish. During his last days, he was a frayed man and, after his usual time spent in the wild, refused to go home. He ventured out into the “grizzly maze,” as he calls it, way later in the season than usual. The bears he knew were all in hibernation, and all the only bears still there were unfamiliar with Treadwell.

If we are to believe Herzog and he many people he interviewed, Treadwell once again got his wish.

Comments on this entry are closed.