Before the advent of home video, a film’s legacy and reputation were based on the memories of people who saw it and whether it continued to play on television.

Starting with its premiere on October 25, 1978—in Kansas City no less—John Carpenter’s Halloween earned its reputation slowly, at theaters and drive-ins around the country, before its legacy was enshrined afterward on television.

Halloween may not have invented the slasher film, but it’s ground zero for every slasher movie that came after it. When watched today, the undisputed horror classic still plays, but it is more like a greatest hits collection of slasher tropes than an organic work unto itself. Forty years later, director David Gordon Green’s new Halloween faces the challenge of recalling the same cinematic feel and paying tribute to its original, while knowing that four decades of slasher films have both ripped off (and evolved from) the 1978 classic.

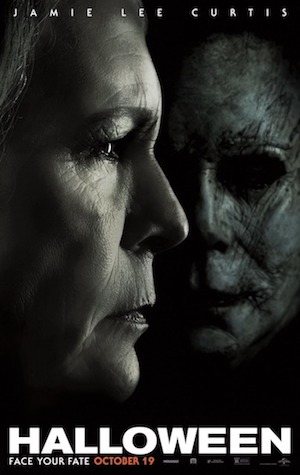

For better or worse, that’s exactly what it does. Ignoring the nine films in between, the 2018 Halloween depicts final-girl survivor Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis) as a grandmother haunted and obsessed by that fateful night in 1978 when her friends were murdered and she barely escaped the deranged knife-wielding boogeyman. We know Michael Myers will be back, and we know there will be another murder spree. Once the dots start to connect, Halloween isn’t quite as satisfying as it is inevitable.

Green has taken special care to evoke the original, from its clever opening credit sequence (a resurrection of sorts) to several strikingly familiar stalking sequences and cat-and-mouse situations—and these touches give the new film a fun sense of symmetry. He even hired Carpenter, who not only directed the 1978 film but also composed its iconic score, to co-create a new score with a similar flavor.

This new Halloween also tweaks the formula by upending just enough plot and character expectations for a couple minor surprises and some well-designed modern-day cultural resonance. The most interesting thing about the new script is that Laurie isn’t just the damaged victim who went on to ruin her daughter’s childhood by stockpiling guns and being paranoid, she is also a force of nature who essentially wills this rematch into existence.

One stylistic choice that distinguished Carpenter’s Halloween but is sorely missing from Green’s film is the slow, menacing movement of the camera up and down the block. I’m not talking about the infamous long POV shot of young Michael (which Green references as directly as possible). No, I mean the perspective that turned the audience into voyeurs, that turned suburbia into a dangerous place. Maybe Green felt the pressure of the quicker pace of modern filmmaking, but that feeling of dread and foreboding just isn’t present here.

The new Halloween was never going to live up to the legacy of its predecessor. But it does evoke the original and take into consideration how audiences have changed since then, which is a minor miracle, I suppose, and it is light years better than the nine films in between.

This review is part of Eric Melin’s “LM Screen” column that appears in the upcoming winter edition of Lawrence Magazine.

Comments on this entry are closed.