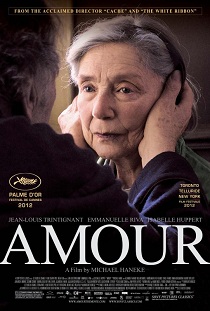

I saw Michael Haneke‘s new interior drama Amour in early December and it took my breath away. Put simply, it already feels like a classic.

I saw Michael Haneke‘s new interior drama Amour in early December and it took my breath away. Put simply, it already feels like a classic.

I knew then it would be number one of my Best Movies of 2012 list, but I dreaded writing about it. Amour is a film that so completely took me over and affected me emotionally that I was scared to revisit it in an in-depth review.

Now that it is opening in wide release, I can’t avoid it any longer. The rest of the cinema world has already embraced it so fully, even in as mainstream an award show as the Oscars, which gave it five well-deserved nominations — a big deal for a foreign film. So I am the last in line, but I’ll try here to add something new to the conversation.

Much has been written about Haneke’s proclivity to torture his audience. The term “provocateur” gets thrown around a lot. Certainly, Amour is provocative as well. It’s an unsettling movie about fragility and mortality that features an elderly French couple nearing the end of their lives. It mostly takes place in their apartment. But don’t let the single setting and depressing premise fool you: Amour is not merely a clinical exercise, as much of Haneke’s work has been categorized. There’s enough honest and wrenching observations about love and death in Amour to fill a Tolstoy novel.

The credit for the warm undertones beneath the anguish should go to Haneke’s extraordinary actors, whose own life experience is on display here. It is key to the movie’s success that the upperclass Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant) and Anne (Emmanuelle Riva) have a rich past together, especially since only glimpses of it are actually referred to in Haneke’s efficient, clear-eyed screenplay. It is this economy of theme paired with the subtle richness of character that make Amour so powerful.

Georges and Anne’s spacious Parisian apartment has been the setting for much shared joy and tenderness but soon it takes on quite a different tone — one that neither of them are prepared for, despite their many contented years together. Anne’s quick decline in health following a stroke forces Georges into caretaker mode, a role he accepts with determination, for he trusts no one else to treat his wife with the respect she deserves. But Haneke’s tough screenplay isn’t interested in showcasing the quiet nobility of the caregiver. His concerns are more pressing and angry. Anne’s condition debilitates both of them, and this place of refuge slowly becomes a tomb, quite literally.

When their middle-aged daughter (Isabelle Huppert) shows up with her own “life crisis,” it’s all noise to Georges. He’s also not willing to accept any talk of plans for the inevitable future. His daughter is of no use to him now. He wants to be alone with his grief. Georges’ selfishness is completely understandable and defensible, and it flies in the face of the “brave warrior” mentality that is generally accepted and perhaps preferred in this situation. Of course its preferred because it makes it easier on other family members, no matter how well meaning they are. This subject matter is ripe for sentimentalization, but Haneke resists it at every turn, opting instead for unflinching honesty.

Haneke’s choice to shoot Amour with a static camera and lots of long takes illustrates the loneliness of the apartment, even as it foreshadows the complete stillness soon to come. (Not to mention a jarring opening scene that lets us know right away what kind of tone will be taken.) There is no score to guide the audience’s emotions either, only the diagetic sounds of classical music as played or listened to onscreen.

The apartment is most certainly empty by film’s end, and when it arrives, it is an absence deeply felt. But it’s not before several startling moments of revelation — and many quiet ones as well. These moments are organically sewn into Haneke’s script and brought to stunning life by Trintignant and Riva’s performances. On one hand, it’s a beautiful notion that a couple happily married for a lifetime can still learn something new about each other in their 80s.

On the other hand, death is a cruel hand to be dealt, and it comes for the wealthy and proud just as it does for the rest of the world’s citizens.

{ 3 comments }

Great review!

This was by far the best movie I’ve seen in 2012, it’s nice to see it being loved overseas aswell.

Thanks, Brendan. For me, it works on all levels: as an intellectual exercise and an emotional one.

We saw Amour last night and were mezmerized by it. It amazes me that the reviews seem to focus on the story line without recognizing that the characters in the movie represented differing attitudes of people surrounding those in their difficult last moments of life; the daughter who loves her parents but cannot tune into what they are experiencing; the nurse whose efficiency precludes caring and understanding; the caregiver who I think the director intentionally made the husband not the wife since wives are the more usual caregivers so the point of helplessness in care giving can be made more dramatically. Each prototype of personality can be forgiven their insensitivity since the force of life is greater than death. So we turn away from the inevitability of our own deaths.

I could go on. It is an amazing film.

Comments on this entry are closed.