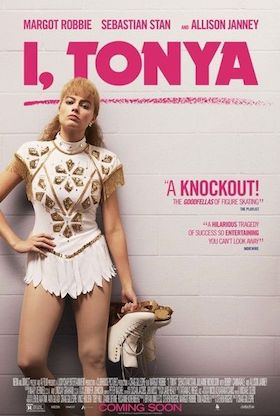

An inside look at maybe the biggest non-O.J. or Clinton news story of the 90s, I, Tonya manages to both inform and entertain. It details the early life, professional rise, and spectacular fall of figure skater Tonya Harding (Margot Robbie), who the film paints as a tragic figure who had the misfortune of being dealt a rotten hand in life. And while most people will come to this film to devour the juicy bits of gossip related to the Nancy Kerrigan incident, the most striking portions deal with the personal struggles of Harding, who got further with fewer favors than anyone in her position could have dared hope for.

I, Tonya is presented faux documentary style, with the actors giving interviews to the camera as lead-ins to the reenacted drama. It opens with a make-up aged Robbie speaking about her childhood, and how her mother (Allison Janney) willed her into figure skating in the same way that a blacksmith forges steel. This brute force parenting is presented with a healthy dose of physical and mental abuse that sets the tone for Tonya’s relationships and personality throughout life. As an adult, Tonya is as abrasive and mean as one would expect considering her upbringing, and when she falls in love, it ends up being with an abusive man, Jeff Gillooly (Sebastian Stan), who is as bad, if not worse, for Tonya as her mother.

Raised on a steady diet of abuse, paranoia, and cruelty, Tonya emerges into adulthood as an exceptional figure skater who nevertheless can’t help but to argue with judges, intimidate opponents, and snap back at any perceived slight. One of the interesting things that director Craig Gillespie does when presenting all of this is to keep rotating between narrators to give a fully informed yet sometimes contradictory account of Tonya’s life. This is a neat trick, as it provides enough coverage of the events to give audiences a general idea of what happened without ever siding with one person or version. Indeed, to do so would have been inappropriate, for real life is never clean-cut enough to separate people like Tonya Harding, her mother, or Jeff Gillooly into strictly good/bad categories. The truth always lies somewhere between the stories, and by revealing the contradictions between the narrators, I, Tonya manages to bolster its believability.

The performances of Robbie, Janney, and Stan aid this effort immeasurably, and are the biggest factors in the ultimate success of the picture. What does or does not work begins and ends with Robbie, who carries the film as Tonya Harding over a span of twenty-plus years. She takes turns being charming, insecure, scared, tough, and admirable, yet never loses sight of the tragic figure she inhabits. Sebastian Stan is also magnificent as Gillooly, who comes off as an idiot who is just smart enough to know that he’s not all that smart. This depressing self-awareness is wrapped up in an abusive ball of timidity that lashes out at Tonya like so many small men who turn to violence as their only available resource.

Yet if anyone deserves credit for putting I, Tonya over the top by way of a dynamic, jaw-dropping performance, it is Janney. As LaVona (Harding) Golden, Janney is a snarling, pitiless viper with a singular purpose: to make her daughter a champion. It would have been easy to play the role of the evil sports mom with a one-sided selfishness that allowed for the film to simply be about Tonya and her struggle, yet there’s serious nuance at work, here. At one point, Tonya’s mom tells her adult daughter that Tonya has every right to hate her, but at least that hate fertilized something special. LaVona herself had a terrible mother that she despised, but she never got anything out of the relationship; at least Tonya got a skating career, she says. It’s a striking take on the role, and one that allows for just enough daylight between the cracks to see a human being in there, somewhere.

This is ultimately a film about class, both in the social (stratified) sense, as well as the personal (manners). I, Tonya views these two aspects of “class” as unique, yet argues that they exist in the same related place: like the opposite sides of a coin. Tonya Harding grew up poor, and in a family that lived in a different universe than most of the others that circulated in the figure skating world. Throughout the film, she runs up against this establishment, which informs her in all frankness that she doesn’t have the desired “look” of an American skating champion.

This is only one side of the coin, however, and as I, Tonya progresses, it becomes clear that who Tonya is as a person is just as much to blame as where she comes from. She might not have the expensive clothes and refined tastes of the other skaters, but her attitude, bearing, and the company she keeps is what will ultimately sink her. The question then becomes one of fate, and whether Tonya Harding ever really had a chance.

Could Tonya have ever overcome her lack of social class to develop some on a personal level? Did the prodigal figure skater ever have a shot at success, or was a rotten mother, an empty bank account, and an unfair world too steep a hill to climb? This is perhaps the film’s only failing: its refusal to plumb these depths. There’s a sort of winking admiration for Tonya Harding beating like a pulse throughout this film, and it is this recurring undercurrent that never allows for a full, meaningful analysis of the woman. And while this isn’t enough to derail the film, it does make for a pressing “what if” when considering the places I, Tonya might have gone. Opening today, I, Tonya is worth checking out, both for the paths taken, and the few it didn’t.

Comments on this entry are closed.