Christopher Nolan solidified himself as a blockbuster filmmaker way back in 2008 when The Dark Knight made over a billion dollars, but it’s the movies he’s made after he became minted that have been fascinating. Inception was genre-bending and complicated, if not unnecessarily convoluted, caper/sci-fi flick that was as much about grief and loss as it was about invading someone’s dreams and implanting an idea.

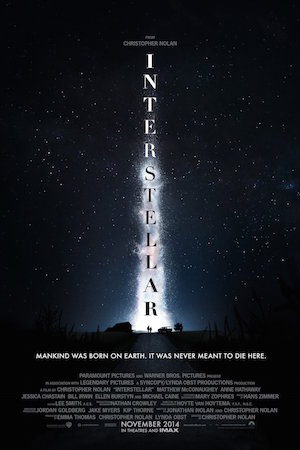

Interstellar is similar to Inception in that regard. Nolan’s film is far-reaching, galaxy-spanning love letter to the science fiction genre (partictularly 2001: A Space Odyssey) that also happens to be about familial duty and the fear of abandonment.

Unsurprisingly, it’s also his most ambitious film to date.

Taking place in the not-too-distant future, Interstellar takes place on a version of Earth in rapid decline. A second Dust Bowl has covered the U.S., entire species of crops have died out and many people with backgrounds in other fields have been essentially drafted into agriculture in a failing attempt to stave off famine. Matthew McConaughey plays Cooper, a test pilot/aeronautical engineer-turned farmer who lives in the dirt, but can’t shake the notion that mankind is meant for something bigger.

After the film’s 45-minute first act, which sets up Cooper’s family, his dilemma and the program that might help him save mankind, he’s finally given a chance to do something about the Earth’s plight. Through a series of strange, seemingly coincidental or narratively convenient events, he ends up at the center of a space mission that involves leaving this solar system behind and scouting new worlds with the hope of finding one that would support human life, and then bringing the rest of mankind along for the ride.

The premise alone is quite an undertaking to setup, and it’s always interesting in sci-fi movies what details get explained and what details are assumed. In Intestellar, Nolan forgoes a lot of the science behind space travel, suspended animation, artificial intelligence and robotics and instead spends his time on larger, more abstract concepts like relativity and the effects of gravity. Neil Degrasse Tyson will likely have a field day with how the movie explains and presents these concepts, but Nolan’s decision to focus on concepts rather than the functional reality of the world he’s creating is another more indirect nod to 2001, which does the same thing.

No matter how far Interstellar ventures from Earth, Cooper’s family remains a focal point. His son Tom (played by Casey Affleck) grows up to become a farmer, his daughter, Murph (played by Jessica Chastain), becomes a physicist and carries a suitcase full of daddy and abandonment issues with her because of Coop’s departure when she was a girl. Their story is simple and straightforward, but is cut into the more visually arresting and complicated central plot of space exploration.

I’ll spare any further plot synopsis, but the best way to think of Interstellar‘s storytelling is as a rocket launch. The movie’s nearly 3-hour runtime spends its first stage establishing the characters, conflict and rising action before achieving lift-off; its second stage is spent pushing into unfamiliar territory; and its third points us in the direction it intended us to go.

Like most science fiction, people will likely be able find cracks in it’s plotting or refuse to suspend belief on some random detail, and Interstellar has its share of sentimental, emotionally manipulative moments, but they’re delivered so convincingly by a strong cast, McConaughey especially, that they still manage to be compelling. The film’s epic scope is justly served by the IMAX format, particularly every scene in space or on a new world.

There’s a remarkable level of ambition here, and while Nolan doesn’t always accomplish what he sets out to do, the end result is still a compelling spectacle that likely won’t carry the same gravitas on a small screen. See it now, or forever hold your peace.

Comments on this entry are closed.