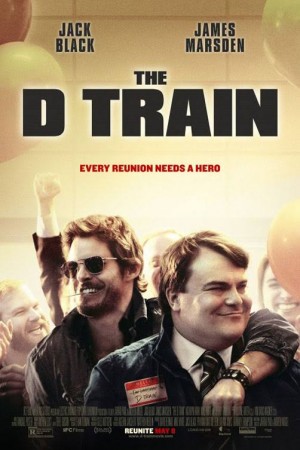

The most notable thing about The D Train, opening today, is Jack Black’s performance as a desperate loser who cannot express the repressed feelings of love that he has for an old high-school friend.

Like his character, Black reaches desperately for sympathy, but doesn’t do enough to earn it in a film about a compulsive liar who ruins his life for the sake of social status. Black uses his signature tightly wound energy to bottle up homosexual feelings underneath the façade of a stock character he and other funny actors have rehashed in other movies: the low-brow suburban man child, whose awkwardness and out-of-touch disposition are usually used for lighter comedic effect.

Black’s performance only goes so far in lending his selfish character any depth or nuance, which would have gone a long way in making him identifiable or sympathetic. The film also seems afraid to examine the main character’s sexuality. Black goes for dramatic effect, but he has difficulty shedding his comedic persona and instead chooses broad comedic strokes to bury any serious questions that The D Train could have raised about the main character’s blatant deception of his family and work colleague.

Dan Landsman (Black), a middle-aged dad from Pittsburgh, is a member of his high school’s alumni association, and is shown trying desperately to fit in with other members of the class of 1994 as they gather and try to convince their former classmates to show up to their 20th anniversary reunion. A life-long outcast among his peers, Landsman’s cloying, immature personality doesn’t endear him to his fellow classmates, who probably should have kicked him out of the alumni association when he declared himself chair of the association and refused to give the other members the password to the class reunion Facebook page.

The film unintentionally shows that Landsman’s classmates have evolved into mature adults over the 20 year interim as they quickly grow fed up with Landsman’s behavior at the beginning of the film. The D Train slips up early on when the film tries unsuccessfully to make Landsman’s immature personality endearingly comedic.

Landsman tries to change his outcast status when he sees the ridiculously named Oliver Lawless (James Marsden), an archetypal pretty-boy actor who was the cool kid in Landsman’s class, on a national TV spot for sun-tan lotion. Black’s character immediately becomes infatuated and tries to convince the other members of the alumni association to invite Lawless to their upcoming class reunion as a last-ditch effort to boost attendance.

And this is where the film’s unaddressed deception comes in. Landsman feels the unmotivated need to come up with a lie so he can fly out to L.A. and convince Lawless to make an appearance at the reunion. He lies to his wife (a sympathetic Kathryn Hahn) and to his boss (Jeffrey Tambor) when he announces that a firm in Los Angeles is interested in doing business with the company Landsman works for. Landsman does meet Lawless, and convinces him to pose as someone from the firm that Landsman and his boss ostensibly flew to California to meet. His deceitful plan works: Landsman’s boss is convinced of the lie, his wife still thinks he’s flown to California for business, and the trip ends with Landsman and Lawless having drunken sex with each other.

After flying back home, Landsman resumes his normal life, having convinced his boss and family that he’s orchestrated a successful business deal for the consulting firm, while sweeping his sexual encounter with Lawless under the rug. But under the surface of the lies that Landsman tries to hide lurk unexamined sexual feelings for Lawless, which come to the surface in the form of the sort of emotional outbursts that are signatures of Black’s comedic style. When Lawless arrives for the reunion, he stays with the Landsmans, and Black’s character continues to latch pathetically onto his former classmate. When Landsman’s lies are revealed near the end of The D Train, his marriage and the company he works for have been wrecked, and the film leaves most of Landsman’s actions unaccounted for and wrapped up neatly in facile, formulaic plot resolutions.

The events in The D-Train reach for comedic undertones. But Black’s comedic style is out of sync with a deceptive character that uses lies for his own selfish ends. The nature of Landsman’s existence as an immature husband and father who cheats and then lies to everyone around him is treated much too lightly. The film lacks any insight about Landsman’s yearning to shed the social outcast status that has seemingly haunted him for the past 20 years, and we are meant to accept him as a well-meaning guy who simply can’t tell the truth.

Landsman’s lies are treated only on the surface, as a way for him to gain acceptance among his peers, long after high school social status should matter to any normal person. We are meant to view Landsman’s and Lawless’ covert gay sex in comedic terms, which the film fails at, because there is no meaningful effect to his sexual liaison or his lies, beyond his wife finding out and only expressing surface-level disappointment that has no dramatic conflict. The D Train operates only on the surface and fails to mask Landsman’s pathological lies with Black’s humor.

Comments on this entry are closed.