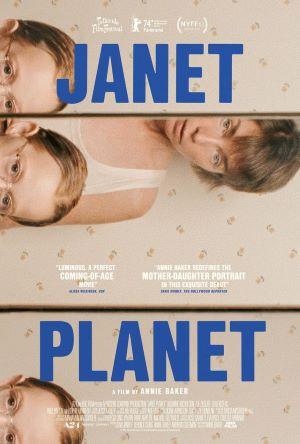

[Rating: Minor Rock Fist Up]

In Theaters Friday, June 28

A slow, often tedious film that rewards a viewer’s patience and resolve, Janet Planet will likely pass through the sieve of the masses like so many life-changing moments lost to a pre-teen’s perspective. An emotional two-hander about a daughter and mother navigating a turbulent and uncertain world with seemingly low stakes, the film revels in the micro-moments that formulate the ways children absorb and reflect their own reality.

The debut directorial effort by playwright Annie Baker, Janet Planet opens with 11-year-old Lacy (Zoey Ziegler) calling her mother, Janet (Julianne Nicholson), from summer camp. Lacy says everyone there hates her, and she’ll kill herself if a rescue isn’t imminent, yet her sudden departure endears a level of sympathy that she hadn’t expected, leading her to go back on her request (to no avail: a partial refund was provided). Once home, Lacy must fight against Wayne (Will Patton), the live-in boyfriend, for Janet’s attention, leading to increasingly bad behavior that culminates in a breaking point for the adult relationship.

Other grownups pass in and out of the lives of Lacy and her mom as well, including the latter’s friend, Regina (Sophie Okonedo), and Avi the actor (Elias Koteas). These chapters allow Baker to create a series of emotionally tactile moments to outline what is essentially a memory piece for a child shot verité-style. Bereft of friends her age (except for a forced playdate with Wayne’s daughter), and essentially in orbit of the eponymous Janet, whose life proceeds in spite of Lacy rather than in service to it, the movie is a meditation on the ways children engage with the character and ethics of the world around them.

The script (also by Baker) is sparse and padded out with scenes unafraid to breathe via long, extended takes shot both close and from afar. It can be frustrating when the seemingly pivotal moments come without any reaction cuts, like during a conversation between Lacy and Janet on their daily mailbox visit, but as the film goes on, the intention comes into focus. Janet Planet is interested in the ways an 11-year-old sees and processes the world around them, asking the audience to experience the characters and events of the picture as Lacy might. The movie isn’t concerned with the pacing and visual rhythm of each scene any more than a child cares to understand the social ethics of a conversation or the power of a line like, “you should break up with him.”

Ziegler does a fine job selling the clever arrogance of a clingy kid that has learned how to leverage the obligated love of an exhausted single parent, yet as the title of the film suggests, this is Nicholson’s show. Janet comes off as a person rubbed raw by single parenthood, crumby romances, and unrealized dreams, and while lesser movies would use the mother-daughter relationship to anchor some kind of redemption for her, Baker doesn’t take the bait. Janet is an overwhelmed person increasingly succumbing to the malaise of a decidedly “mid” life, and Lacy is the echo that will reverberate from it.

It’s thus a brutal and honest look at adolescence, adulthood, aging, and the crushing inevitability of life. If developmental psychologist Robert Kegan is to be believed, humans are meaning makers, and Janet Planet seems to be an exploration of what it means to construct a personal epistemology to make sense of the world (via Lacy’s perspective and Janet’s example).

It might not always be the most fun, but Janet Planet commits to the conceit of its broader intention, allowing the audience to understand what it feels like to absorb an outlook and personality through uninterrupted moments of confusion, tedium, longing, and despair. The world is a strange and ever-shifting platform upon which any stability is hard-won, especially for a pre-teen trying to make sense of conversations and relationship dynamics well above their paygrade. Again, a more sentimental (and less brave) film would have presented a story with an enduring, courageous mother shepherding an adorable child through the rigors of a quirky life, but Baker is searching for something more genuine, here.

Lacy kind of sucks; Janet’s life kind of sucks; the people orbiting Janet kind of suck (though some less than others). That’s life, though, isn’t it? Again, Janet Planet isn’t an especially entertaining movie to watch, and the characters in it aren’t a very good hang. The story is about as sincere as they come, though, and rings with an authenticity that is aided in no small part by Baker’s set-ups and shot selections (for better and worse). At once a thesis on meaning-making at a formative age as well as a treatise on the legacy of parenthood, the film is a revelatory slog.

Comments on this entry are closed.