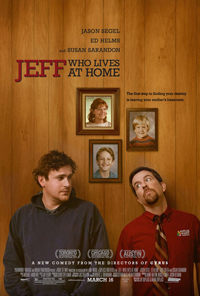

Mumble Core pioneers Jay and Mark Duplass continue their trek in to the mainstream with their latest film Jeff, Who Lives at Home. This intimate portrait of a broken, yet lovable family gives viewers a quirky story, fascinating characters and compelling performances, but the hands-on camera work and the almost claustrophobic framing upends most of the film’s emotional appeal.

Mumble Core pioneers Jay and Mark Duplass continue their trek in to the mainstream with their latest film Jeff, Who Lives at Home. This intimate portrait of a broken, yet lovable family gives viewers a quirky story, fascinating characters and compelling performances, but the hands-on camera work and the almost claustrophobic framing upends most of the film’s emotional appeal.

Since the death of his father, Jeff (Jason Segel), an aimless, pot-smoking 30-something, has been searching for his destiny. His obsession with the movie Signs is as hilarious as it is sad, and has shaped Jeff’s worldview. Simple day-to-day events aren’t just random ruptures to a meaningless landscape, but a vast and purposeful tapestry of meaning each leading to Jeff’s purpose.

Even a trip to the local hardware store becomes a trial or adventure, either a distraction from the quest Jeff is on or the very reason for his existence. Neither Jeff’s mother, Sharon (Susan Sarandon), nor his brother, Pat (Ed Helms), understands Jeff’s outlook.

Even a trip to the local hardware store becomes a trial or adventure, either a distraction from the quest Jeff is on or the very reason for his existence. Neither Jeff’s mother, Sharon (Susan Sarandon), nor his brother, Pat (Ed Helms), understands Jeff’s outlook.

Sharon believes that a difficult childhood caused Jeff to become stuck, while Pat sees Jeff as actively avoiding adult responsibility. Either way, a wrong number and a request for wood glue set Jeff on a path that will soon include Pat, Pat’s wife Linda (Judy Greer), and her co-worker and possible lover. All of this occurs while Jeff searches for a mysterious Kevin.

I struggle with how successfully Jeff, Who Lives at Home tells its story. Just as in Signs, every name, gesture, or personal trait leads to an ending that is manipulative in a way that calls for either a groan or a chuckle. This overt construction may give us a means to discuss the nature of created narrative.

I struggle with how successfully Jeff, Who Lives at Home tells its story. Just as in Signs, every name, gesture, or personal trait leads to an ending that is manipulative in a way that calls for either a groan or a chuckle. This overt construction may give us a means to discuss the nature of created narrative.

Why do we continue to create and tell stories, and what function do they serve in our contemporary world? Should they simply reflect life, or should they manufacture the type of meaning and structure that “real” life lacks and we as individuals desperately desire? Jeff, Who Lives at Home may emerge from some hybrid of these queries.

As a cerebral film, Jeff, Who Lives at Home is interesting. Jeff follows a series of “clues” that could never lead to the outcome that he arrives at anywhere but within the context of a constructed narrative. It is not believable, but I’m not convinced that it is supposed to be. This quandary would more satisfying had the execution of the story been more elegant and emotionally appealing.

As a cerebral film, Jeff, Who Lives at Home is interesting. Jeff follows a series of “clues” that could never lead to the outcome that he arrives at anywhere but within the context of a constructed narrative. It is not believable, but I’m not convinced that it is supposed to be. This quandary would more satisfying had the execution of the story been more elegant and emotionally appealing.

The Duplass brothers have some compelling performances to work with. Segel is often utterly vacant and at the same time engaging. We feel sorry for Jeff and drawn to his lack of cynicism. He is a believer. Helms also crafts a multidimensional character in Pat, who is insecure and guarded, but desperately wants to be vulnerable and connected.

These performances are squashed by the Duplass brothers’ devotion to overt and jumpy camera work that gives the viewer almost exclusively single shot close-ups of each character.

These performances are squashed by the Duplass brothers’ devotion to overt and jumpy camera work that gives the viewer almost exclusively single shot close-ups of each character.

The jump of the camera and its constant reframing feels almost entirely unmotivated. There is never enough consistency in the movement to denote any reinforcement of the onscreen content, nor does constant movement serve the emotional tone of the film. It is a distraction throughout.

The single shot close-ups draw us into each character individually and keep them emotionally separate from one another.  Though this serves the film early on, I was desperate for a two shot that could illustrate some growing emotional connection between the characters later in the film. One moment between Pat and Jeff in a hotel bathtub had me breathing a sigh of relief once I finally saw the two framed together, but these moments are too few especially late in the film and we are left with a bunch of separate characters that never really seem to fit together.

Though this serves the film early on, I was desperate for a two shot that could illustrate some growing emotional connection between the characters later in the film. One moment between Pat and Jeff in a hotel bathtub had me breathing a sigh of relief once I finally saw the two framed together, but these moments are too few especially late in the film and we are left with a bunch of separate characters that never really seem to fit together.

This lack of connectivity between characters may serve to underline that this is a story full of made up characters, which do what the storytellers tell them to do. If that’s the case then Jeff, Who Lives at Home may be an interesting exercise or cinematic talking point, but its overt and handsy camera work and lack of surprises or any satisfying emotional appeal undermine the strength that it could have had.

Comments on this entry are closed.