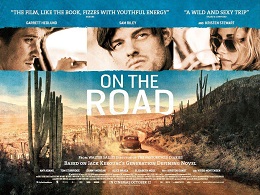

On the Road, the long-awaited movie adaptation of Jack Kerouac’s seminal literary masterpiece, really purrs when it is working, yet falters when director Walter Salles veers off-course and pushes his characters into a hyper-realized state of self-importance. When it is at its best, the film finds the perfect symbiotic balance between Kerouac’s prose and the solemn beauty of the open road, where the adventures of a young dreamer plant the seeds of not only one man’s future, but an entire generation of literary hopefuls. And while there are a few instances where the picture stumbles, it’s not enough to completely sour On the Road for any except the die-hard Beatnik fanatics, who will no doubt quibble with a few of the movie adaptation’s deviations.

On the Road, the long-awaited movie adaptation of Jack Kerouac’s seminal literary masterpiece, really purrs when it is working, yet falters when director Walter Salles veers off-course and pushes his characters into a hyper-realized state of self-importance. When it is at its best, the film finds the perfect symbiotic balance between Kerouac’s prose and the solemn beauty of the open road, where the adventures of a young dreamer plant the seeds of not only one man’s future, but an entire generation of literary hopefuls. And while there are a few instances where the picture stumbles, it’s not enough to completely sour On the Road for any except the die-hard Beatnik fanatics, who will no doubt quibble with a few of the movie adaptation’s deviations.

The first of these changes comes early on, when Kerouac’s literary alter-ego, Sal Paradise (Sam Riley), meets his future traveling buddy, Dean Moriarty (Garrett Hedlund). Although Moriarty would answer the door buck naked later in the book (which the picture also showcases), the novel is quite clear about the fact that “Dean came to the door in his shorts” this particular time. In retrospect, this almost feels like a deliberate choice, as if the director is signaling his intention to liberally deviate from the narrative to serve his purposes, and those bearing any grudge against this ought to go ahead and bolt while the going is still good.

Indeed, Mr. Salles takes a number of liberties, including the expansion of Neal and Carlo’s relationship beyond what is simply implied in the book, and a total reworking of the Plymouth man’s interaction with the boys from Part Three of the novel (there was no sex in the book, and in the film he was driving a Chrysler). Some of these elaborations and deviations make sense when viewed with an understanding eye, for the book and corresponding film are both about the same thing: Dean Moriarty. The latter work’s expansion on the former’s core might not be faithful in the technical sense, yet all changes (except for the Plymouth becoming a Chrysler, that’s just weird) seem to serve the purpose of adding more definition to Dean’s character, albeit with details from Kerouac’s later works.

Indeed, Mr. Salles takes a number of liberties, including the expansion of Neal and Carlo’s relationship beyond what is simply implied in the book, and a total reworking of the Plymouth man’s interaction with the boys from Part Three of the novel (there was no sex in the book, and in the film he was driving a Chrysler). Some of these elaborations and deviations make sense when viewed with an understanding eye, for the book and corresponding film are both about the same thing: Dean Moriarty. The latter work’s expansion on the former’s core might not be faithful in the technical sense, yet all changes (except for the Plymouth becoming a Chrysler, that’s just weird) seem to serve the purpose of adding more definition to Dean’s character, albeit with details from Kerouac’s later works.

This is understandable, as Dean acts as the catalyst for Sal’s adventures on the highways and back roads of the United States, and allows the young writer to grow into the man that would inspire millions. Although it seems an impossible feat, Mr. Salles uses the expanded Dean character to weave together a stable, coherent narrative out of the handful of trips and years that make up Kerouac’s literary opus. Admittedly clunky to start, for the film doesn’t give its audience any time to get used to the self-aggrandizing characters or their lofty prose, On the Road eventually settles into the tone of its source, and never looks back.

Scenes of Sal wandering across the mid-west against the backdrop of a setting sun, or leaning casually in the back of a flatbed pickup, notebook and pencil in hand, color in the movie’s blank spots and give an unspoken voice to the novel’s presence just under the surface. For fans of the book, most of what one might hope for is there, including a hilarious encounter with Sal’s family during a Christmas feast, where Dean, Marylou (Kristin Stewart), and Ed Dunkel (Danny Morgan) swing through to scare the squares. Dialogue is often pulled straight out of the book’s pages to fill the back and forth banter of the movie’s characters, along with Sal’s own narration, which is a real treat.

And for those unfamiliar with Kerouac’s work, it should give some insight into the romantic draw of the man, and why his brand of iconoclastic self-discovery speaks to so many people. It’s quite simple, really: Sal’s quest is an inherently American proposition. In the country where any person is supposed to be able to write their own future, to make their dreams come true, one young man’s journey west, into that old land of promise, speaks to a national trait as unique to this country as baseball or jazz. The film adaptation successfully portrays this theme in its leads’ several adventures, and shows how Sal matures and comes to realize that he needs no muse, no guide; that the cult of Dean Moriarty is a sham: that the road is his one true religion.

And for those unfamiliar with Kerouac’s work, it should give some insight into the romantic draw of the man, and why his brand of iconoclastic self-discovery speaks to so many people. It’s quite simple, really: Sal’s quest is an inherently American proposition. In the country where any person is supposed to be able to write their own future, to make their dreams come true, one young man’s journey west, into that old land of promise, speaks to a national trait as unique to this country as baseball or jazz. The film adaptation successfully portrays this theme in its leads’ several adventures, and shows how Sal matures and comes to realize that he needs no muse, no guide; that the cult of Dean Moriarty is a sham: that the road is his one true religion.

Yet as good as the film is, it pulls up just short of great. When the picture is cooking, and going at full-tilt as it is during the jazz club and New Year’s Eve scenes, it is a blast. Yet when Salles’ On the Road veers off to dip into the sordid love triangles kicked up in the wake of Dean’s tramping, it stalls. The decision to spend so much time here seems curious, for these sub-plots were never more than percolating just beneath the surface in the novel, and though it was definitely an important component of Dean’s make-up, it didn’t define the literary work as much as what’s seen in the cinematic adaptation.

Still, special mention should go to Kristen Stewart and Garrett Hedlund, both of whom really commit to their roles with a brutal honesty and fearlessness that should not be overlooked. Viggo Mortensen is, as always, absolutely stunning as well, for his portrayal of Old Bull Lee (William S. Burroughs) is nothing short of a revelation.

Still, special mention should go to Kristen Stewart and Garrett Hedlund, both of whom really commit to their roles with a brutal honesty and fearlessness that should not be overlooked. Viggo Mortensen is, as always, absolutely stunning as well, for his portrayal of Old Bull Lee (William S. Burroughs) is nothing short of a revelation.

In Sam Riley (Sal Paradise/Jack Kerouac), the film has its one weak link, and being the lead, it’s a pretty big one. He possess neither the rugged physical stature of Kerouac, the proper vocal intonation, nor the onscreen presence to match Hedlund’s un-caged animalism. Like the film as a whole, Riley does a good enough job to get the nuts and bolts of the story across, and even has a few flashes of brilliance, yet there aren’t enough of these moments to string together into something properly brilliant.

{ 1 comment }

It sounds as though I need to stick with Heart Beat, the 1980 John Byrum film which is so oft overlooked.

I think it did two things exceptionally well, which it seems were missing from On the Road. The first is to give emotional substance to Kerouac’s writing which is mostly frontal lobe even when he’s discussing matters of the heart. The second is that Heart Beat is not an adaptation of On the Road, and avoids the pitfalls of direct comparison.

To be honest, I think the Beats are self-indulgent pricks who seem to push the bounds of what’s acceptable not because of the injustices that those bounds create, but simply because there is a boundary. This comes with an utter disregard for damage done to anyone nearby, but Heart Beat is still an incredibly touching film that explores the lives of Kerouac and the Cassady’s in a way that feels vibrant and vulnerable.

Comments on this entry are closed.