Sometimes, I watch movies and just marvel at the fact that everything has been done already.

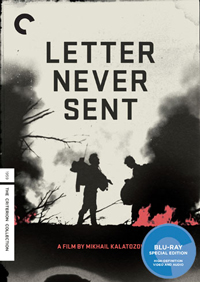

Watching the 1959 Soviet film Letter Never Sent (aka The Unsent Letter), directed by Mikhail Kalatozov and lensed by his brilliant director of photography Sergei Urusevsky, it struck me over and over again how inventive and evocative the shots were and how stale modern film language can be.

Watching the 1959 Soviet film Letter Never Sent (aka The Unsent Letter), directed by Mikhail Kalatozov and lensed by his brilliant director of photography Sergei Urusevsky, it struck me over and over again how inventive and evocative the shots were and how stale modern film language can be.

Whether its a sharply contrasted deep-focus shot with a close-up profile of a weather-beaten face (Innokenti Smoktunovsky) in the foreground and a silhouetted rescuer descending the ladder from a helicopter or a meticulously choreographed handheld shot that follows four Soviet geologists through the brush and puts you right there with them, Letter Never Sent (or Neotpravlennoye Pismo) is a visual wonder for all of its 96-minute running time.

Mikhail Kalatozov is famous for his 1957 Palme d’Or-winning war drama The Cranes Are Flying and I Am Cuba, his semi-hallucinogenic 1964 celebration of the Cuban Revolution. But Letter Never Sent is the overlooked movie that was sandwiched right in between.

What is remarkable is how quickly Letter Never Sent can whip from being a realistic survival story to an impressionistic one, sometimes within the same minute. The cinematography is also shifting POV constantly. In one frantic scene of our heroes digging desperately, it goes from menacing low-angle shots to ones that mirror the action of the pick-axes from above.

What is remarkable is how quickly Letter Never Sent can whip from being a realistic survival story to an impressionistic one, sometimes within the same minute. The cinematography is also shifting POV constantly. In one frantic scene of our heroes digging desperately, it goes from menacing low-angle shots to ones that mirror the action of the pick-axes from above.

The location footage is impressive, combining artistically framed landscape shots with in-your-face close-ups of branches, smoke, and trees ,so it’s all the more noticeable (and a little jarring but no less beautiful) when it suddenly shifts to a studio-shot scene.

Narratively, Letter Never Sent is pretty weak. It begins with some onscreen propaganda titles about the noble journey of the geologists. Three men and a woman are sent into the unforgiving Siberian wilderness in search of diamonds. The leader of the group (Smoktunovsky) continues to write a letter to his wife that he didn’t get a chance to send before their last stop in civilization. As he writes, Kalatozov superimposes images of serenity and contentment that serve as a stark contrast to their surroundings.

The other three geologists are involved in a love triangle (shared by Tatyana Samoilova) that is by turns slightly tedious and uncomfortably transparent. Thankfully, Kalatozov doesn’t let it take center stage. In fact, it is just simmering below the surface of some of the scenes that are filled with the most tension.

The other three geologists are involved in a love triangle (shared by Tatyana Samoilova) that is by turns slightly tedious and uncomfortably transparent. Thankfully, Kalatozov doesn’t let it take center stage. In fact, it is just simmering below the surface of some of the scenes that are filled with the most tension.

Certainly, the group is idealistic, but their faith in the fact that their mission will bear fruit is often shaken. Eventually, just as it seems their fate has changed, it drastically changes again. Once they are faced with a far greater challenge — survival itself — the tone of Letter Never Sent drastically changes. All of the superimpositions of fire in the preceding scenes turn out to be a literal foreshadowing as the group fights for their lives.

For a Criterion Collection Blu-ray and DVD, this edition is sorely lacking in the kind of bonus content one would expect. There is the normal high-quality booklet, this one featuring an essay by film scholar Dina Iordanova, but other than that, no bonus features. That may speak to how overlooked the movie is. I read somewhere online that Francis Ford Coppola owned one of the few prints that anyone knew about of this film, previously referred to as The Unsent Letter.

It’s a good thing Criterion has restored it, and I have no doubt that its place in history as a visual wonder will be certified, not unlike I Am Cuba‘s, after more people see it.

Comments on this entry are closed.