[Rating: Swiss Fist]

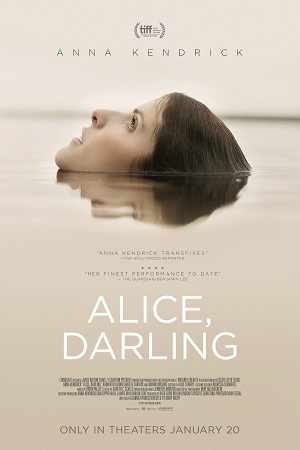

In Theaters Friday, January 20

Five pounds of movie stuffed in a 10-pound bag, Alice, Darling has its heart in the right place (even if it can’t manage that trick for its characters). Framed by micro-aggressions yet constructed as a broad meta-text on psychological abuse, the piece struggles to ground the drama amidst the push-pull of these two worlds. Buoyed by the performances of leads that convincingly sell the trauma and heartbreak of it all, the movie is less of a story and more of a snapshot: teasing the profound while never quite arriving there.

When Alice (Anna Kendrick) meets up with friends Tess (Kaniehtiio Horn) and Sophie (Wunmi Mosaku) one evening, everyone seems to be walking on eggshells. Tess and Sophie are drinking wine and talking about an upcoming birthday trip at the lake while Alice is nervously checking her phone with every chime. It’s clear these women share a healthy and deep history together, yet something is off, and no one is addressing it between the steady stream of iPhone text alerts. Furtive glances and scowls passed when Alice isn’t looking speak volumes, especially once the audience meets the sender of all the messages: Simon (Charlie Carrick).

Handsome, outwardly charming, and quietly cruel, Simon lords over girlfriend Alice with a gentle, measured consternation that would make Nurse Ratched envious. Although the full scope of his psychological abuse doesn’t come into complete focus for a bit, Alice’s behavior tells the audience most of what they need to know. Rehearsed excuses for the smallest inconveniences, manic hair-pulling, and panic attacks at the mere hint that Simon might get upset all paint a picture of an abuse victim trapped within the prison of their trauma. When the three girlfriends escape to a cabin for their planned birthday trip, hard truths (and even harder decisions) emerge that threaten to reshape the nature of their relationship.

The unspoken dynamics of the Alice-Tess-Sophie friendship triad do much of the narrative heavy lifting early on and remain a strength of the picture throughout. A hidden wince when Alice opts out of sharing wine in favor of a vodka-soda, or the knowing glances passed between Tess and Sophie when their friend hides a full dinner plate under a napkin speaks volumes, and bring the audience up to speed on where this friendship stands. The trio are close, and Alice’s behavior is obviously a departure from the dynamic, yet as the movie dives into its second act, the focus stays on the trauma itself rather than those experiencing it.

Sophie and Tess’ behavior indicate that Alice wasn’t always like this, that Simon has contributed to an unhealthy change in their friend, yet who that person was (or could be) remains unclear throughout. Alice uses her job as an excuse/prop to go on the birthday trip, but it’s never revealed what she does, or who she is outside of a (girl)friend. And while this may be the point (that she’s lost in her trauma), it doesn’t give the viewer any idea of what this story and its characters looked like before Simon arrived on the scene.

And while the audience feels bad for Alice, the script doesn’t give them much of a reason to root for her (Tess and Sophie are far more sympathetic in this regard). It’s clear that she’s become so consumed by the strictures of this relationship that the real Alice got swallowed up by this manic creature pulling out her hair by the fist-full, yet seeing who that person was would have gone a long way towards establishing some much-needed audience investment. A subplot about a search party for a missing girl near the lake house teases at both the metaphor surrounding Alice’s own emotional disappearance, as well as foreshadowing a possible future for abuse escalation, yet that’s all this movie does: tease at bigger ideas.

The broader macro-narrative of Alice, Darling is clear—so clear, in fact, that it takes all of 15 minutes to take the temperature of the whole affair. Abuse comes in many forms, and the way people process their trauma, and the form that takes, can appear in a variety of shapes and sizes. It takes more than a bad guy and a victim to make a story work, though, and that’s pretty much all this one has going for it.

Director Mary Nighy and cinematographer Mike McLaughlin make all of it look nice, even if the settings don’t evince any particular region or locale (this could take place pretty much anywhere). And while Kendrick does a decent job in the lead, doing a lot of capital-A Acting that believably alternates between placid and panicked, it’s Mosaku and Horn who are the true standouts here. Both actors do magnificent work dancing around their friend’s trauma, and have the harder task of selling the pained exhaustion of trying to pull a friend back from the brink without accidentally pushing them over that same ledge.

Even so, it’s less of a film and more of an idea of one, highlighting some very genuine and real human interactions without any of the legwork of establishing who those people are. Authentic to the world it creates (however narrow it might be), as well as the trauma of a broken, abusive, one-sided relationship, there’s enough here to hold one’s interest, even if the end result is something akin to an uninvested shrug.

Comments on this entry are closed.