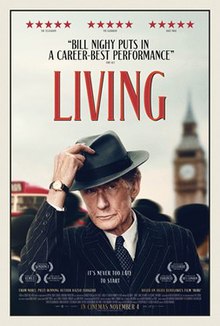

[Rating: Solid Rock Fist Up]

In Theaters Friday, January 20

A story about the holding patterns people put themselves in while waiting for life to happen, Living uses the journey of one man to paint a broader tapestry of self-inflicted injustice. Exploring themes of deathbed regret and circular bureaucracy, the picture will sneak up on a viewer if they aren’t careful, lulling them into sleepy complacency before dropping an emotional hammer.

The film opens at a train station platform on the outskirts of London in the early-1950s, where Mr. Wakeling (Alex Sharp) is taking the temperature of his new co-workers on his very first day. Stoic, officious, and without any inclination towards small talk, these public works employees take after their boss, Mr. Williams (Bill Nighy), whose cold, humorless demeanor sets the tone for the office. A model of bureaucratic inefficiency and adherence to protocol, it is taken as nothing short of earth shattering when Mr. Williams declares that he will be leaving work early that day.

The audience learns the reason for this premature departure is a doctor’s appointment, where a physician informs Mr. Williams that he has just 6-9 months to live. Widowed, and living with a son and daughter-in-law who care more about their inheritance than the patriarch, Mr. Williams finds himself adrift and looking back at a life that seems to have added up to little. After taking some money out of his savings, Mr. Williams goes on a search for meaning and experience, starting first with a broke poet as his guide (Tom Burke), then moving on to a free-spirited woman from his office, Miss Harris (Aimee Lou Wood).

The journey itself isn’t much of a revelation, exploring familiar carpe diem themes through the lens of a terminally ill old man who ultimately realizes that it’s never too late to make a difference, yet the route there is rich with texture and nuance. Although Nighy remains at the center the story, the screenplay by Kazuo Ishiguro makes good use of Mr. Wakeling as an audience surrogate to peel back the layers of truth that Mr. Williams is himself only just discovering. This broadens the scope of the picture outside of one man’s journey and speaks to the specific time and place Living exists.

A remake of Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru, which itself was crucially and meaningfully set in post-war Japan, Living is similarly looking both forward and backwards. After all, this is about more than just one man’s surrender to functionary monotony, but an entire culture’s capitulation to obedience over individuality. Some might point to the war as the cause for this seemingly noble trade-off, but as Mr. Williams points out late in the picture, he’d always dreamed of being little more than a proper gentleman: his ambitions never rising much higher than respectable anonymity.

Director Oliver Hermanus wisely uses Sharp, Wood, and others to dress the scenes so that Nighy can color them with just a single grunt, nod, or pained sentence. The way he frames many of the scenes to put barriers between Williams and those around him (and the absence of them at other times) adds thematic depth to the story and fills in the gaps left by character silence. Likewise, the muted color palette, while period appropriate, allows for narrative flourishes that guide the audience emotionally without being too direct or explicit.

This is the Bill Nighy show at the end of the day, however, and while the orchestra he leads is a large one, he’s the conductor. Again, the broad themes of the picture are clear early on and leave no doubt about where all of this is headed, yet Nighy manages to infuse each scene with just enough pained (and guarded) truth to make each development and revelation impactful. A scene early on in Living where Mr. Williams practices his “I’m dying” speech, yet can’t manage to get the words out for fear of breaking the stoic shield he’s faithfully held up for 70+ years, is both shattering and crucial to who he is.

It’s an affliction the audience sees passed down from father to son, and is a peek into a broader social chain that keeps these seeds re-planted in each generation. Nighy, who probably grew up in a sea of Mr. Williamses, plays the role with a lived-in familiarity that allows the actor to escape wholly into the role (and it’s a delight to witness). His posture, bearing, and even the way he hooks an umbrella over his forearm put him squarely in this world and communicate an authenticity impossible to fake. Seemingly robotic, it serves as a foundation for the sincerity that drips out of Mr. Williams when he begins to take honest stock of a life barely lived.

It is a rich, devastating, yet ultimately heartwarming performance within a movie that is a bit fat in the third act, and just a touch too slow in its first. Hermanus wisely leans on Nighy throughout it all to carry Living, which he does and then some, helping to craft a movie that is more than just a remake, but rather a reimagining of an already familiar tale. Making good use of the supporting cast to broaden the story outside of one man’s look back on a disappointing life still in progress, Living finds the honesty in both its characters and the world they inhabit.

Comments on this entry are closed.