Those who complain that Woody Allen’s best creative years are behind him aren’t paying attention to his full body of work. He’s been more or less releasing one film a year since 1971, and while folks are quick to remember the likes of Annie Hall and Manhattan, with the occasional flash of brilliance like last year’s Blue Jasmine thrown in, they often neglect to realize that the auteur’s lesser films aren’t limited to the last decade-plus.

His frenetic, always-on approach is also responsible for A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy, Radio Days and Mighty Aphrodite. The point is, no matter the artist, churning out work at such a fast pace removes the guarantee of always producing greatness. There’s an equal chance you’ll end up with an artistic equivalent of rice pudding.

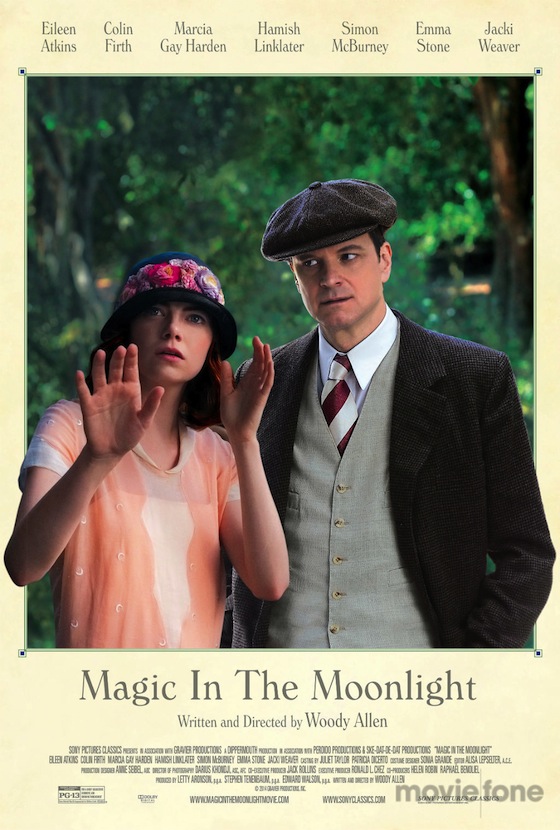

This is where Allen’s latest, Magic in the Moonlight, lands. It’s not terrible, but it’s far from his best. This is Allen playing it safe, with material that’s familiar both in the setting, which bears close resemblance to Midnight in Paris, and the theme (spirituality and skepticism, unlikely romance). It’s entertaining enough, but doesn’t make much of an impression.

This time around, the plot centers on another of Allen’s favorite subjects, the world of professional magic. Colin Firth is Stanley Crawford, a stage magician in the 1920s who performs tricks as the fashionably exotic Wei-Ling Su, a self-proclaimed Oriental master. After he’s approached by a fellow magician and old school friend (Simon McBurney), Stanley travels to a vacation house on the Cote D’Azur, where a wealthy American family is hosting a beguiling young psychic (Emma Stone). Stone’s Sophie Baker appears to be the genuine article, but Stanley is determined to reveal her as a fraud.

This time around, the plot centers on another of Allen’s favorite subjects, the world of professional magic. Colin Firth is Stanley Crawford, a stage magician in the 1920s who performs tricks as the fashionably exotic Wei-Ling Su, a self-proclaimed Oriental master. After he’s approached by a fellow magician and old school friend (Simon McBurney), Stanley travels to a vacation house on the Cote D’Azur, where a wealthy American family is hosting a beguiling young psychic (Emma Stone). Stone’s Sophie Baker appears to be the genuine article, but Stanley is determined to reveal her as a fraud.

While the dialogue is light, witty and fun, and the actors (particularly Firth, Stone and McBurney) do an excellent job with the material, Magic in the Moonlight often feels like the product of lazy writing. The film suffers from an overabundance of “exposition-speak,” explaining plot details and relationships with obvious, unnatural lines of dialogue instead of showing them in subtler ways.

Also, on an intellectual level, Allen’s exploration of spiritual vs. logical thinking ends not so much with any conclusions, but with a noncommittal shrug of the shoulders. One gets the feeling that, after years of asking those big questions that used to occupy his mind so much; he hasn’t really come up with any answers so much as he’s stopped caring.

On the other hand, the technical details of the film are really quite impressive, from the costumes to the set design to Darius Khondji’s lush cinematography. Even if the movie leaves much to be desired in other areas, it excels in all things visual and atmospheric.

On the other hand, the technical details of the film are really quite impressive, from the costumes to the set design to Darius Khondji’s lush cinematography. Even if the movie leaves much to be desired in other areas, it excels in all things visual and atmospheric.

In the end, Magic in the Moonlight is decent fun to watch, but doesn’t really leave the viewer with any food for thought. On the whole, the film is about as challenging as an episode of Masterpiece Theater. While that kind of comfort can be nice coming from a lesser filmmaker, with someone of Allen’s intelligence and talent, it’s disappointing. The writer-director’s latest offering is a trifle, a minor artistic whim painted onto a great big canvas simply because he had the resources to do it.

Comments on this entry are closed.