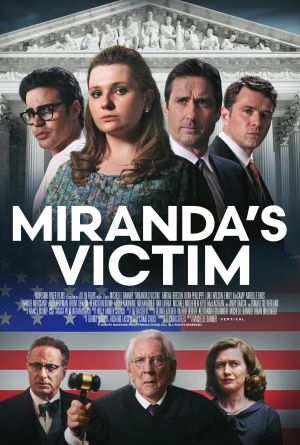

[Rating: Rock Fist Way Down]

In Theaters October 6th

Thematically adrift, morally ambivalent, and emotionally stunted, Miranda’s Victim is a special and unique kind of awful. An assembly of moments that read like audition sides stitched into a loose narrative, the movie never achieves anything resembling believability, cohesion, rhythm, or even basic continuity. An interesting idea with good intentions smothered by clichéd writing and sophomoric directing, the movie is a clinic in telling vs. showing from start to agonizing finish.

Miranda’s Victim uses the Supreme Court case of Miranda v. Arizona as its cause belli, but just what it is about in a broader sense is never defined. At times it is an exploration of the woman, Patricia Weir (Abigail Breslin), whose rape and kidnapping served as the basis for the original case against Ernesto Miranda (Sebastian Quinn). Yet the movie abandons Patricia for big chunks to focus on Ernesto and his lawyers, who argue (convincingly) that the police and legal system didn’t afford the accused man enough Constitutional protection against self-incrimination and coercion.

The movie isn’t done there, though! A good portion of the 2nd act is dedicated to the detective working the case, Cooley (Enrique Murciano), whose investigation is no less convincing in establishing that Ernesto is very much guilty of this heinous crime. A better movie would have forced the audience to grapple with their collective notion of morality and ethics by pitting the correct thing to do (fighting for the rights of the accused) against perceptions of what is just (punishing a rapist), but Miranda’s Victim never seriously explores this conundrum. No, instead it clears out space for the actors to do scene work that mines individual moments for a series of dramatic slam dunks that contribute little to the overall narrative.

Director Michelle Danner is a “world-renowned acting coach” according to her IMDb bio, and her list of notable students reads like the call sheet of this movie. One wonders how much of Miranda’s Victim might have been salvaged if the guiding force behind the project had been more interested in telling this story versus giving students enough runway to hit all of the emotional peaks in each scene. For example, a subplot about Patricia’s mother arguing against any action to report the crime is driven so far into the ground that it nearly comes out the other side, yet it gives the actors involved multiple runs at a scene that is re-worked and re-heated no less than four times.

Danner can’t be faulted for writing the clumsy, exposition-heavy dialogue, though, which operates on a 1960s-sitcom level. It all feels less like a period piece set in the 1960s and more like something crafted by people who drew their inspiration from reruns of Green Acres or My Three Sons. None of it reads as authentic, and with the exception of Murciano, the actors all fail to sell any of it as legit.

Structurally and on a technical level, things are somehow even worse, though. The film employs a series of flashbacks and flashforwards that do nothing for the emotional or narrative elements of the story, starting things in 1966, jumping back to 1963, then forward to 1965, forward again to 1967, back to ’63, and finally to 1976 for a coda no one asked for. What’s more, several scenes seem to exist just to give a bit part enough heft to lure in someone who owes a favor (cough-cough, Kyle MacLachlan), making deliberate what a good script and director could accomplish with a clever line or background bit.

It’s just sloppy, really. Hell, in one scene, a character is admonished for using “that word,” yet no such utterance is shown, meaning the moment was lost in a round of editing and no one seemed to notice. It’s almost on a Wiseau-level in its (lack of) quality and incompetence, and decisions like casting a 27-year-old as a virginal, impossibly innocent high school girl don’t help. Interesting, honest moments that explore the ways Ernesto is exploited by the police and his own attorneys, or Patricia’s remarkable courage to confront her attacker, fall by the wayside in lieu of the next dramatic interaction.

The movie’s indecision over which narrative thread to explore, and its inability to combine any of them into a challenging exploration of justice vs. morality, leaves the viewer emotionally adrift and unsure who/what to root for. The format of the narrative evolves at a dizzying rate as well, going from a character study to a police procedural to a legal drama in the span of an hour. Luke Wilson and Ryan Phillippe appear in the back half of Miranda’s Victim as dueling attorneys when it all turns into an overwrought Matlock episode, though their only real contribution is to allow Miranda’s Victim to flirt with the so-bad-its-good genre.

This is entirely by accident, of course, and is due in large part to the good work audiences have seen these guys turn in over the years. It makes what is on display here simultaneously fascinating and inexplicable: like the sight of a zebra walking on its hind legs in downtown Manhattan. It’s instantly recognizable, yet weird and beyond any reasonable explanation all at once (much like Miranda’s Victim itself). As one might with a bipedal Hippotigris, it’s probably best to just leave this one alone to its own nonsensical devices.

Comments on this entry are closed.