In the wake its 2017 Best Picture Academy Award win, Moonlight is receiving an expanded release by distributor A24, appearing in some 500 additional theaters nationwide. If that award–or the Best Actor honors bestowed on Mahershala Ali, or the film’s Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar– has raised even the slightest interest in you, here’s why you should make sure to get out to see it.

In the wake its 2017 Best Picture Academy Award win, Moonlight is receiving an expanded release by distributor A24, appearing in some 500 additional theaters nationwide. If that award–or the Best Actor honors bestowed on Mahershala Ali, or the film’s Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar– has raised even the slightest interest in you, here’s why you should make sure to get out to see it.

Even more importantly, if Moonlight doesn’t sound like the film for you, here’s why you should see it anyway.

One of Moonlight’s greatest strengths is also its biggest marketing challenge: it defies easy classification. A coming-of-age film, a black film, a gay film, a “life in the ghetto” film–Moonlight is all of these yet both larger in vision and more intimate in scope than such labels suggest.

It tells the story of a young black male, Chiron, growing up in an impoverished area of Miami as he wrestles with his identity, his sexuality, and his place in this often brutal environment. At the same time, it’s not an “issue” or “message” film.

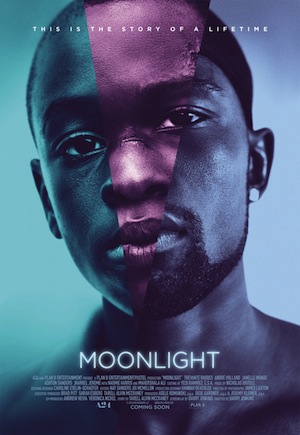

Director / screenwriter Barry Jenkins presents Chiron’s story in three chapters, each at a different age and featuring a different actor: Alex Hibbert as the fearful child the other kids mockingly call “Little”; Ashton Sanders as the quiet, introspective teen; and Trevante Rhodes as the adult now known as “Black.”

Along the way, Chiron attempts to understand the bullying he experiences, the homophobia that surrounds him, and his own confusing sexual urges. He struggles to reconcile his mother’s (Best Supporting Actress nominee Naomie Harris) crack addiction with his affection for Juan (Mahershala Ali), the drug dealer who has taken him under his wing. He finds a confidant, shares a first kiss, and suffers the pain of betrayal.

Throughout, Jenkins never settles for the simplistic, sidestepping or outright contradicting the easy clichés that often come with this narrative territory. Juan doesn’t take Little under his wing to enlist him as a drug runner; he takes him back to his (decidedly middle-class) home and offers him soup and a place to stay for the night.

And in one of the film’s most touching scenes, Juan brings Little to the ocean and teaches him to swim by showing him how to float–how to relax and trust in the water, and in Juan’s cradling arms. This floating is literal and metaphorical, a reflection of Chiron’s search for people and places that will support him and will afford him the opportunity to discover and be himself.

The gorgeous cinematography by James Laxton portrays these events in the colors of a bruise: rich blues, blackish purples, and yellowish ochre, contrasted from time to time with Miami’s ice cream pastels and the vivid blue of the ocean.

Most importantly, Jenkins respects his characters. He portrays them not as good or bad, but as complex and challenged. They’re not symbols or role models or cautionary tales. They’re scared and brave, flawed and heroic, honest and deluded. The conclusion, as it is, finds the adult Charon an active agent in his own life, yet still in development, still conflicted.

Moonlight provides a rare opportunity to share their experience and, in particular, to get a glimpse into Charon’s journey. And that is one of cinema’s great gifts.

Comments on this entry are closed.