This movie review of Mr. Turner appears at Lawrence.com.

This movie review of Mr. Turner appears at Lawrence.com.

[Solid Rock Fist Up]

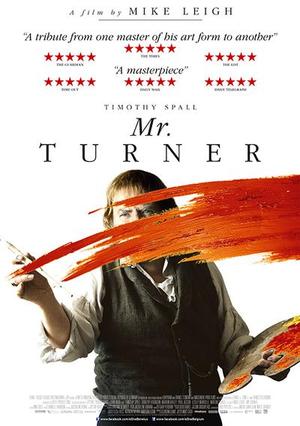

Early-19th-century artist J.M.W. Turner is now regarded as an innovator, elevating landscape and maritime paintings to high art. But by the time of his death in 1851, his work had fallen out of favor for being too abstract.

Director Mike Leigh’s biopic of Turner isn’t exactly abstract, but it’s definitely hard to pin down because it so carefully avoids the pitfalls of the genre. Rather than the standard series of career highlights and easy motivations told in flashbacks, Mr. Turner is almost a pure character piece. The facts of his life must often be inferred while everyday moments that are seemingly inconsequential to the “plot” of the movie build a rich portrait of a man full of contradictions.

Timothy Spall plays Turner, a waddling middle-aged chipmunk of a man who speaks mostly in grunts. His passion — which excludes all other pursuits in life — is capturing natural light and the sublime beauty of nature on canvas.

Turner lives a simple life with his beloved father (Paul Jesson), who makes sure he’s in constant supply of paint and canvas, and a soft-spoken housekeeper (Dorothy Atkinson), whom he casually takes advantage of sexually when the mood strikes him.

He neglects his former lover and their kids, brushing them off with the same indifference that he gives to art critic John Ruskin (Joshua McGuire), who is actually an enormous supporter of Turner’s work.

Mr. Turner covers 25 years of the contradictory painter’s life, and it often feels like it, moving at a languorous pace over its two-and-a-half hours. Like it’s subject, however, the film has an irascible charm. Leigh strips away the myth of the vaunted artist; the highly evolved being with special knowledge that sees into the souls of others. He also avoids the clichés that come with portraying an artist of Turner’s stature.

In London’s snobbish Royal Academy of Arts, Turner toys with the chattering gossip hounds and his fellow Romantic painters. Craving approval, his compatriots swirl around the great halls — filled to the brim with works of art — while Turner relishes his position of standing. With one tiny yellow speck of paint dust, added to one of his masterpieces on the spot, he silences them all.

Leigh’s unusual screenplay strategy is well documented, and it pays dividends here once again. He and his actors research and rehearse extensively without a script to place them in the characters’ present. Through these improvisations, a narrative is formed. All the actors have an unassuming naturalistic acting style per usual, but it’s also clear that Leigh did his own extensive research on Turner’s life, incorporating very specific and personal details, right down to the painter’s last words.

In contrast to the understated acting, the cinematography is expansive and stirring. Director of photography Dick Pope received a completely deserved Oscar nomination for his ravishing work on Mr. Turner, which emulates and achieves the rich, dramatic colors of its subject’s paintings.

For all of his gruffness and contradictions, Turner is a man who revels in the sublime beauty of art. An early scene in Mr. Turner encapsulates his paradoxes. At a party, Turner is so moved by a girl playing a Purcell aria on a harpsichord that he stops to sing along. It’s a moment that mirrors his place in the art world, as Turner’s voice is scratchy and off, even as his deep appreciation for the music is so finely tuned.

Comments on this entry are closed.