[Rating: Swiss Fist]

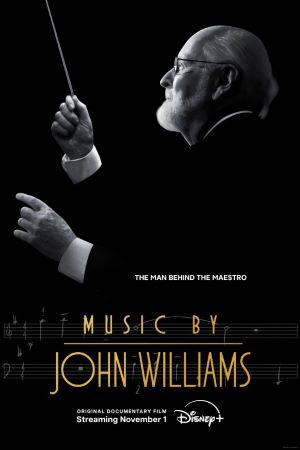

Streaming on Disney+ Friday, November 1

A toothless love fest that too often coasts on the goodwill of its eponymous subject, Music by John Williams is the best kind of “book report” documentary in the same way that a Big Mac is the best kind of “fast” food. Both are nostalgic, filling, tasty, and appealing to the masses, yet neither will nourish a discerning customer looking for depth, nuance, or surprises.

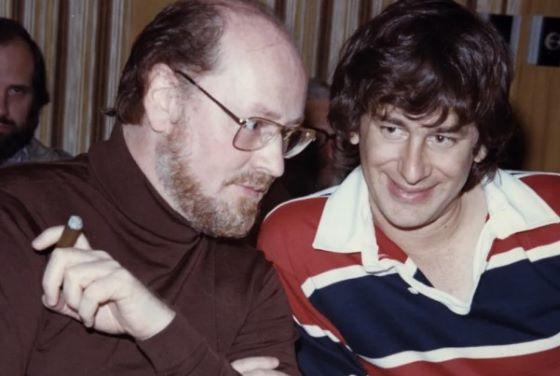

After a best-of talking head montage to start things off, all of whom extoll conductor/composer John Williams’ creativity, originality, and textbook knowledge, it falls to Steven Spielberg to explain how the two came to collaborate in the 1970s. Spielberg explains that scores were falling out of favor at that time, with source music from the likes Simon and Garfunkel in The Graduate on the rise. The director and composer shared a common vision about the importance of original instrumental music as a component of the narrative, and starting with 1974’s Sugarland Express, one of the most successful Hollywood collaborations was born.

Director Laurent Bouzereau shifts the doc’s focus from here to Williams’ upbringing, his introduction to score composition, his love of jazz, and the composer’s first job in St. John’s, Newfoundland. It sticks with the linear biography for a bit, touching on Williams’ early days as a studio musician for a number of television series while juggling a marriage and 3 kids at home. His transition into film composition comes next, including his credit change from “Johnny” to “John,” which signaled a stylistic shift in his output right around the time he hooked up with Spielberg.

Bouzereau uses the remaining hour-plus to highlight the seemingly endless catalogue of Williams scores that have burned a hole through the nostalgic fabric of western pop culture. Williams himself talks through the composition process of his pieces in Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Raiders of the Lost Ark, E.T., Harry Potter, Star Wars and more, with Spielberg and others lending a few now-legendary anecdotes (like Williams’ unveiling of the Jaws theme on his living room piano). It’s not just fluff, either, as George Lucas, Ron Howard, Alan Silvestri and a host of others talk about the ways these movie scores did more than just entertain: they supplemented narrative and character development to make those films what they were.

Indeed, J.J. Abrams says at one point, “That’s the thing about John Williams: as good as the material he’s getting [is], he always makes it better. He always finds a way to tap into the essence of what makes it moving, or meaningful, or resonant.” All of which is to say that the documentary makes an iron-clad, nay, impenetrable case for Williams’ brilliance, influence, and creative insight.

Here’s the thing, though: no one would argue against that, not even the stuffy classical music snobs that briefly drove Williams out of the Boston Pops in the 1980s. Bouzereau is selling water to the thirsty, here, and never delves too deeply into anything that might challenge the hagiographic narrative propping all of this up.

There are interesting flashes that pop up for a few vanishing seconds, like when Williams’ oldest child talks about her father’s long absences from home and somewhat hands-off parenting. Another comes when Williams is reminiscing on the phenomenal success of Star Wars, which he admits was a turning point in his life. Someone excitedly told him about people lining up around the block to see the film not long after its release, yet Williams admits he shrugged the moment off, remarking, “I didn’t experience that at all. I was so completely occupied with what was in front of me.”

Although Bouzereau doesn’t seem to think so, this fleeting moment forces one to wonder if it was all worth it, if one more movie score was enriching or meaningful enough to take a pass on some well-deserved enjoyment of the moment (or more time with his kids). Perhaps an exploration of those ideas and questions are a different documentary altogether, but at least that one would have explored territory not already known to most audiences. And to be fair, it’s hard not to smile throughout most of this, nor to marvel at the texture Williams’ music has added to some of the most memorable movie experiences of the last 50 years.

There are a few scenes that showcase archival footage of Williams at work (like during the E.T. composition with Spielberg), and it’s a fascinating peek inside the magic-making process. But that’s all Music by John Williams is or strives to be: a backstage pass into a familiar world where cherished movie music comes to life. A thrill for a time, sure, and good enough for a few casual stories about what goes on out of sight and behind the scenes, but there’s not much here for those already familiar with Williams or the industry at large.

Comments on this entry are closed.