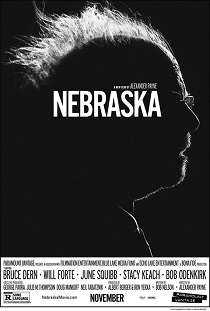

Having grown up in Omaha, Alexander Payne has long been fascinated with the Midwest. His movies Election and About Schmidt were at least partially set in his hometown, so its fitting that his sixth feature as director is tilted simply Nebraska.

Having grown up in Omaha, Alexander Payne has long been fascinated with the Midwest. His movies Election and About Schmidt were at least partially set in his hometown, so its fitting that his sixth feature as director is tilted simply Nebraska.

What’s interesting to note, however, is that Nebraska is the first movie he’s directed without a writing credit and yet it bears the familiar Payne stamp of melancholy mixed with hard-edged satire, while still feeling very personal.

Bruce Dern plays Woody Grant, a wild-haired old codger from Billings, Montana who is dead set on getting himself to Lincoln, Nebraska to claim the million dollars he says he’s won through a direct-mail sweepstakes notification. It’s no matter that his mild-mannered son David (Will Forte) and spitfire-of-a-wife Kate (June Squibb) have told him repeatedly that its a scam — he’s dead set on it.

You get the feeling that Woody hasn’t been dead set on much in his 70-plus years, so he’ll make the 800-mile trip even if he has to walk. From the opening scene where a trooper picks Woody up on the highway, I was instantly reminded of David Lynch’s The Straight Story, in which in an old man travels from Iowa to Wisconsin by lawnmower to reconcile with his estranged brother.

Nebraska has a similar leisurely pace and elegiac tone, but it’s also buoyed by Payne’s acute familiarity with Midwestern stoicism and his uncanny ability to squeeze absurd comedy from the most banal of situations. David’s job as a home-theater salesman isn’t going so well and his girlfriend recently moved out, so he decides that maybe a spur-of-the-moment road trip to his family’s home state is just what he needs. Besides letting the old man live out his fantasy of becoming rich man, he’ll be able to reconnect with him as they drive through Wyoming and South Dakota.

Nebraska has a similar leisurely pace and elegiac tone, but it’s also buoyed by Payne’s acute familiarity with Midwestern stoicism and his uncanny ability to squeeze absurd comedy from the most banal of situations. David’s job as a home-theater salesman isn’t going so well and his girlfriend recently moved out, so he decides that maybe a spur-of-the-moment road trip to his family’s home state is just what he needs. Besides letting the old man live out his fantasy of becoming rich man, he’ll be able to reconnect with him as they drive through Wyoming and South Dakota.

The problem is that his father isn’t interested much in talking — even when they stop in their (fictional) hometown of Hawthorne, Nebraska to visit Woody’s brother Ray (Rance Howard) and his family. Hawthorne is pretty typical of small-town America, with a dilapidated downtown that probably looked that way even before the economic crisis five years ago. But despite its bleak, worn-out setting, Nebraska its has its own sense of grace. This is at least partly due to the striking black-and-white cinematography of Phedon Papamichael, which seems like an elegy for the rural Midwest. It brings to mind Peter Bogdanovich’s 1971 look-back The Last Picture Show, but that film approached its subject matter with way more nostalgia.

Nebraska achieves a certain poise also in the way that Bob Nelson‘s screenplay withholds key information about its characters, revealing unexpected deeper layers as the film progresses. Dern’s portrayal of Woody takes on new shades, and its impossible not to warm up to him, just as the emotional resonance of his story sneaks up on you. New faces paint a clearer picture, from Woody’s conniving old business partner (Stacy Keach) to a reflective older woman who runs the tiny newspaper down the street (Angela McEwan).

A sort of mystery begins to unfold about why the Grants left Hawthorne. But, of course, it does so quietly, so you may not even realize what’s happening. Payne is constantly trying to find the balance between broad comedy (as evidenced by Squibb’s plainspoken, foulmouthed barbs) and a serious portrait of culturally isolated people who have no use for self-awareness. Payne illustrated a similar sensibility in About Schmidt, and here he walks the tightrope between ridiculousness and truth even more perilously. I still can’t decide whether David’s dunderheaded cousins (Tim Driscoll and Devin Ratray) are the result of dry comic genius or whether they steer too far into parody. I know for a fact, though, that there are plenty of people who will be able to relate to the scene where all the men– during the first family reunion in 20 years — gather around the TV to watch the game.

A sort of mystery begins to unfold about why the Grants left Hawthorne. But, of course, it does so quietly, so you may not even realize what’s happening. Payne is constantly trying to find the balance between broad comedy (as evidenced by Squibb’s plainspoken, foulmouthed barbs) and a serious portrait of culturally isolated people who have no use for self-awareness. Payne illustrated a similar sensibility in About Schmidt, and here he walks the tightrope between ridiculousness and truth even more perilously. I still can’t decide whether David’s dunderheaded cousins (Tim Driscoll and Devin Ratray) are the result of dry comic genius or whether they steer too far into parody. I know for a fact, though, that there are plenty of people who will be able to relate to the scene where all the men– during the first family reunion in 20 years — gather around the TV to watch the game.

It’s no coincidence that Woody Grant is almost an anagram for Grant Wood, the famous painter of “American Gothic.” Dern is so natural in the role that he barely seems to be acting, lending Woody a dispassionate quality that could easily be mistaken for indifference if it weren’t for the few moments when he is jarred suddenly into the present. If those around him haven’t noticed it yet, Woody has begun a serious self-examination. And he’s finally decided he wants something more from his life. Whether that something is a truck — or something else — no one will ever know for sure. Because he’s not talking about it.

{ 2 comments }

Loved the movie. Your review is pretty much spot-on. I knew most of the archetypes portrayed in the movie growing up with my aunts and uncles, grandmother and grandfather and cousins in Nebraska. Sweet strange memories – a visit on a sweltering day in Bloomfield just north of Plainview, sitting in my Great Uncle’s non air conditioned living room staring at us as if we were from another planet when the the conversation died down – my grandmother letting us break the little yellow dye packet in an oleo bag and letting us mix it to look like butter – my grandfather taking us fishing and telling us to be quiet lest we scare the fish – thousands of memories.

Thanks for your excellent review.

Mark – I really appreciate your comment. It sounds like this movie really hit home for the both of us.

Comments on this entry are closed.