[Rating: Swiss Fist]

In Theaters December 6

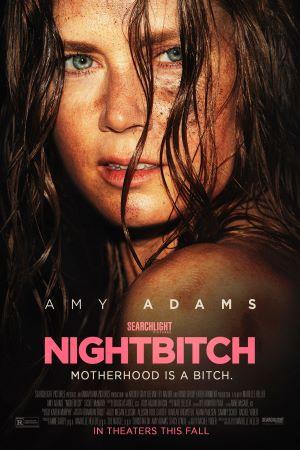

A movie about an over-burdened, under-slept housewife that begins to literally transform into a dog as she passes through different phases of a mid-life crisis? Let’s go! Toss in Amy Adams turning in one of the best performances in a career stocked to the breaking point with them, and this must be a home run, right…right? Alas, the high hopes for Nightbitch go largely unrealized, and what worked as a fantastical abstract rumination in Rachel Yoder’s 2021 novel just doesn’t translate all that well into a film.

Credited simply as Mother (Adams), Husband (Scoot McNairy) and Son (shared by twins Arleigh and Emmett Snowden), the family of Nightbitch is an altogether normal looking one from the outside. Comfortably middle-class, white, and American, Mother has given up her career as an artist to raise her toddler son while Husband leaves for whole days at a time on work trips. The sheen of motherhood has dulled, however, and what may have once been an exciting journey has transformed into something of a domestic prison.

Mother is tired of eating the same hashbrowns every morning and cleaning up shit on the regular; she can’t stand the cloying chirps from the other moms at the library’s toddler meet-ups, and she spends what little free time she has looking back with longing at the life she gave up for all of it. A chance encounter at the local playground with a pack of wild dogs stirs something inside of Mother, however, and she begins to see physical changes beyond those wrought by the trauma of childbirth. Just how much Mother is actually transforming into a literal dog, and how much of it is connected to postpartum depression and a sense of lost identity inform the back half of Nightbitch, though it would be a mistake to assume that this metamorphosis is what the movie is all about.

A good chunk of the film comes through Mother’s narration about her past and present, where she finds herself reflecting on the resurfaced memories of her own mom, who died when she was young. Recollections of her mom’s struggles connect Mother to a communal experience that allows her to share frustrations not just about the daily grind of taking care of another human, but also over the remorse of what’s surrendered to make that happen. And while Husband isn’t the focus of that resentment, his clueless ambivalence to what his spouse is going through begins to foster something resembling that.

“How many women have delayed their greatness while the men around them didn’t know what to do with theirs?”

Mother considers the question as she feels herself slipping further away from the person she once was, grieving this loss as she revels in the simple joys of being a parent. She experiences this conflict at the same time that she starts experimenting with evening runs with the local dog pack, paired with canine rearing analogues to connect with Son. All of this she does while meditating on the violent, primal nature of childbirth, and the ways modern western society has kidnapped the experience in favor of light pastels, mylar, and mini cupcake platters. And while this is interesting and rich material for reflection, those coming to Nightbitch for the body horror and a Rick Baker transformation a-la Thriller are going to come away disappointed.

What’s more, director Marielle Heller steers into the contemplative and metaphorical aspects of Nightbitch at the expense of character and plot, and though this might have worked for the book, it doesn’t do the movie many favors. Other than Mother, the characters don’t exist as fleshed out people with realized personalities or histories outside of what’s necessary for the story. The neighborhood moms and even Mother’s old art-world colleagues are just physical manifestations of the larger struggle, and they take turns being both antagonists and allies depending on the needs of the somewhat schizophrenic script. There’s a brief moment when Husband vocalizes some of his own frustrations and disappointments, yet the idea disappears along with any true sense of who he is as a character outside of his function in Mother’s trajectory.

The thing of it is: it’s a worthwhile trajectory, and it is brought to life by one of the best actors of her generation. Adams surrenders herself to the role of Mother both physically and emotionally and gives a performance that communicates much of what the script’s narration bludgeons the audience with. Mother’s exhaustion and despair never veer into anything too exaggerated or schlocky, even during the heaviest dog moments, and Adams manages to balance all this emotional turmoil against a genuine sense of love for Son.

It would have been easy to turn this into a dark tale about a woman going crazy, but that would have been a disservice to Adams and all the other moms of the world whose struggles are too quickly assigned to a person cracking under the pressure. But there’s just not a lot going on other than this rumination and passing gimmick. This gives Nightbitch the flavor of a movie with an interesting first and third act that feels like it’s missing the most crucial elements of its second.

Which is all to say that Nightbitch delivers on its premise in its own not terribly cinematic way, and without the grotesque creature effects certain folks might be looking for. This is a movie about what it means to be a mother in the most literal sense, and connects to ideas about how women function at a primal level in the modern world. Less of a film and more of a mid-life meditation nuzzled inside a career-best performance, Nightbitch won’t have many howling at the moon, but it’s not going to get buried in the backyard, either.

Comments on this entry are closed.